Rome, Carthage, and the History of the First Punic War (264-241)

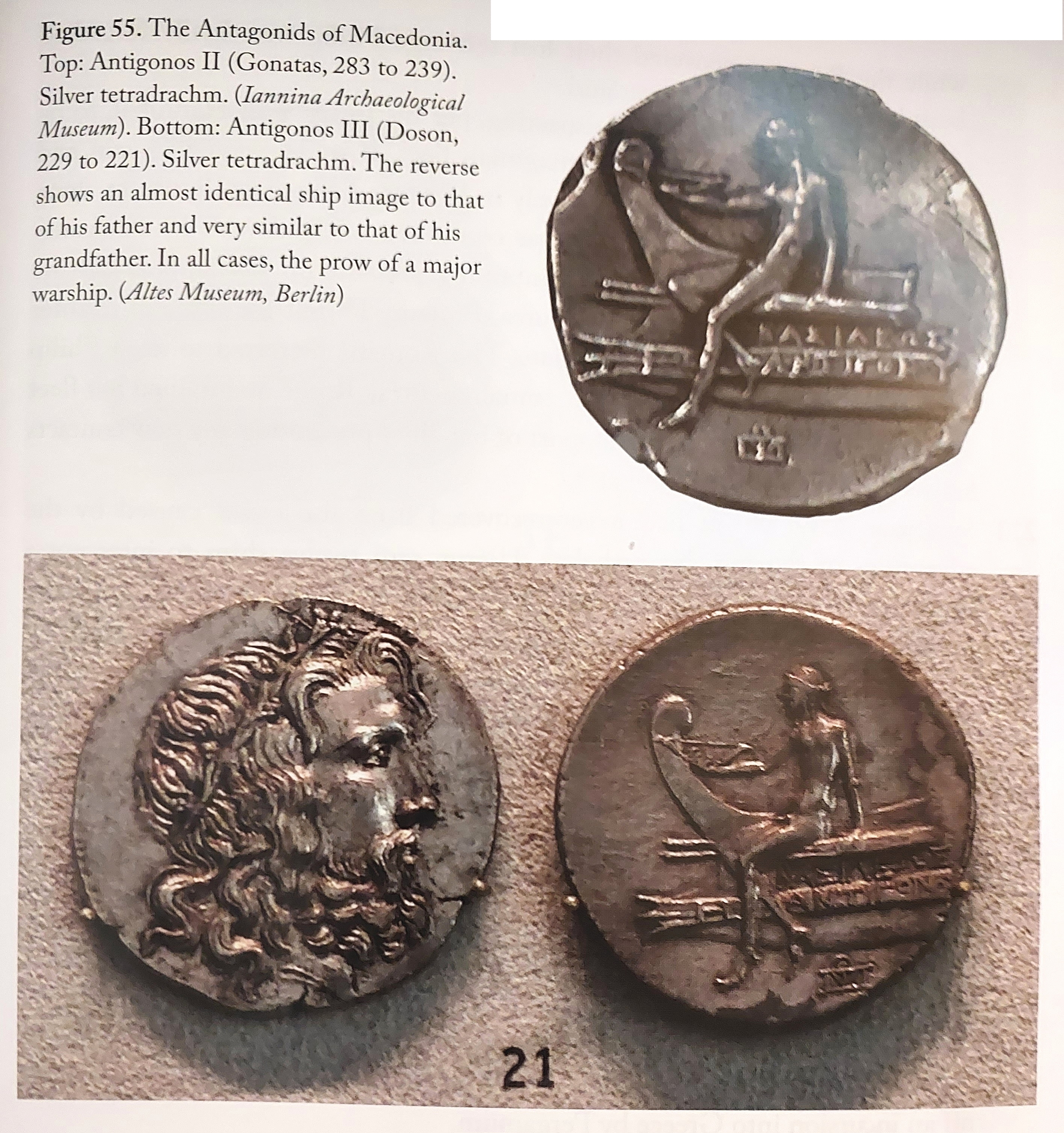

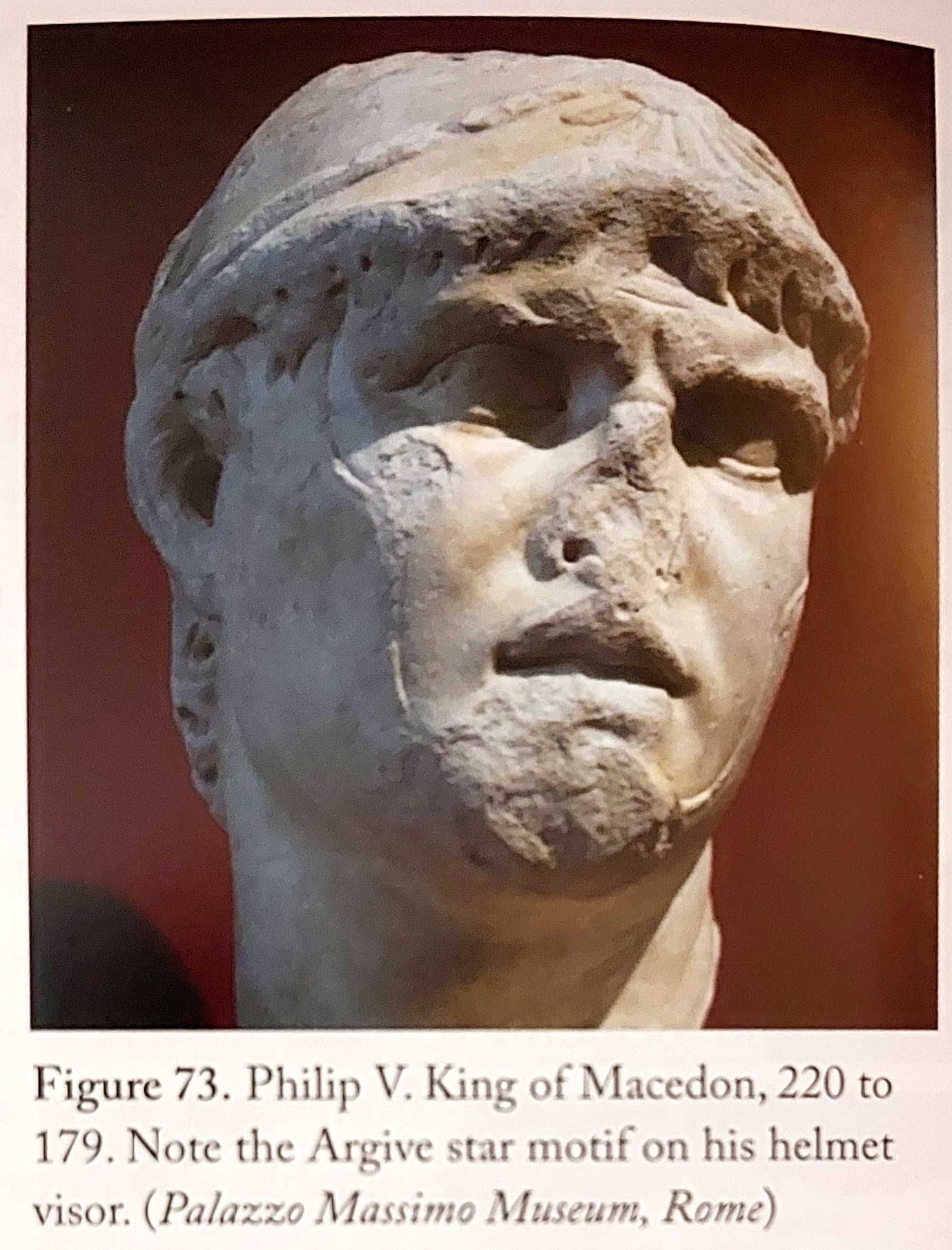

Polybius, the Megalopolitian historian who had been brought to Rome in 167 BC, explained that the Hellenistic world was a multipolar one. The major eastern powers were the successor states of the Alexandrian empire following the Partition of Babylon by the diadochi in 323, kingdoms commanded by Alexander’s generals, Antigonus (Macedon), Lysimachus (Asia Minor), Ptolemy (Egypt), and Seleucus (Babylon).

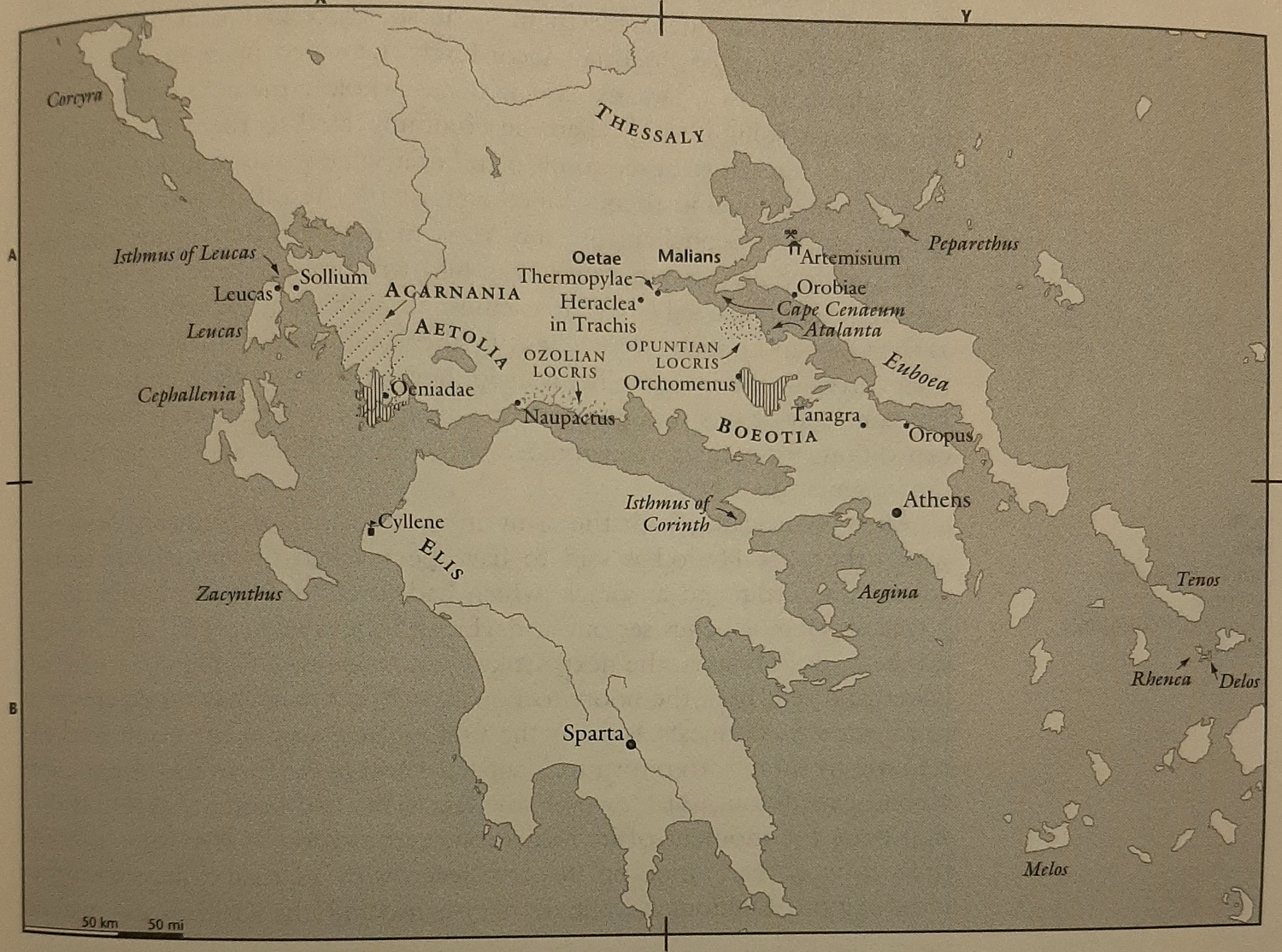

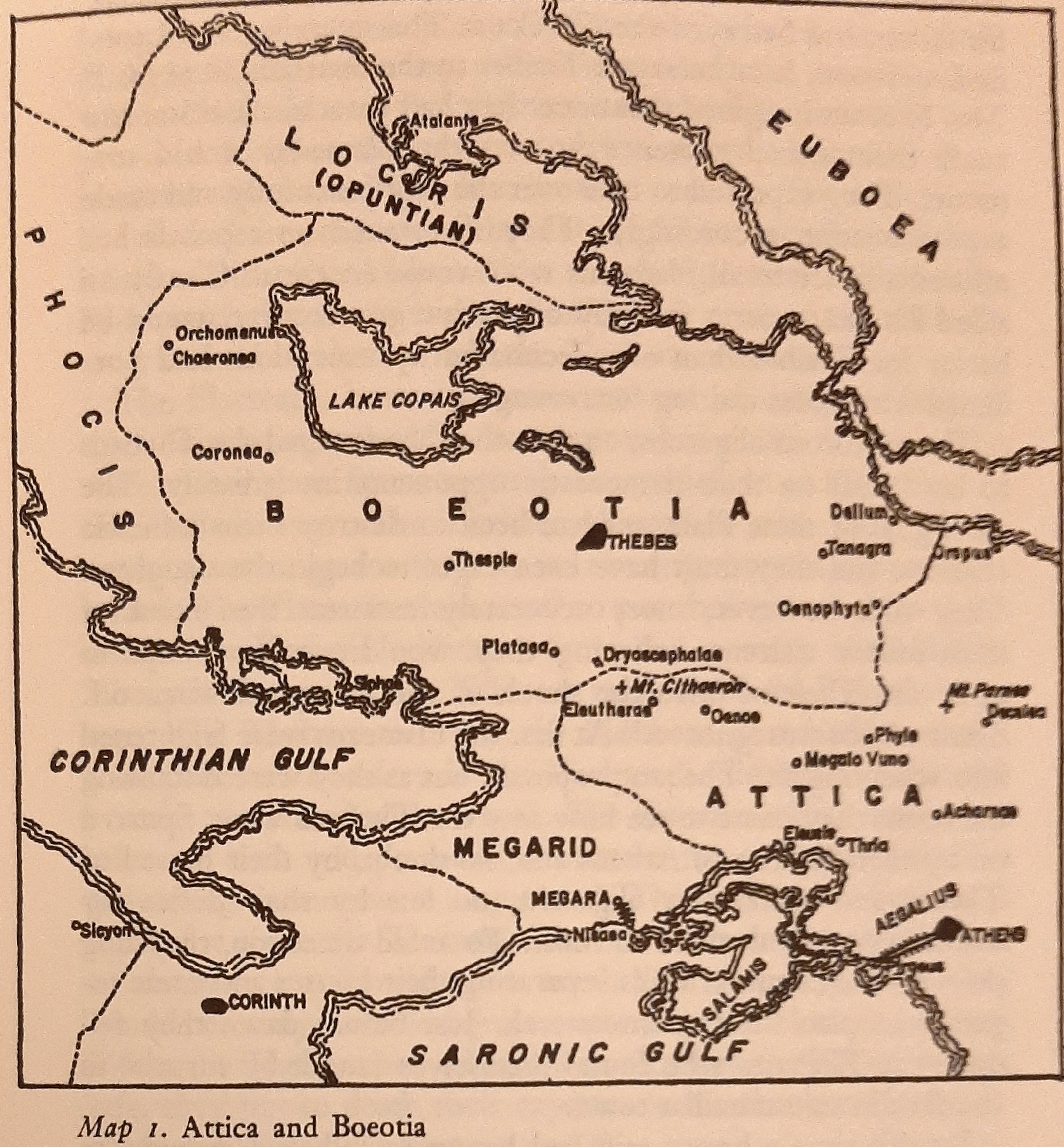

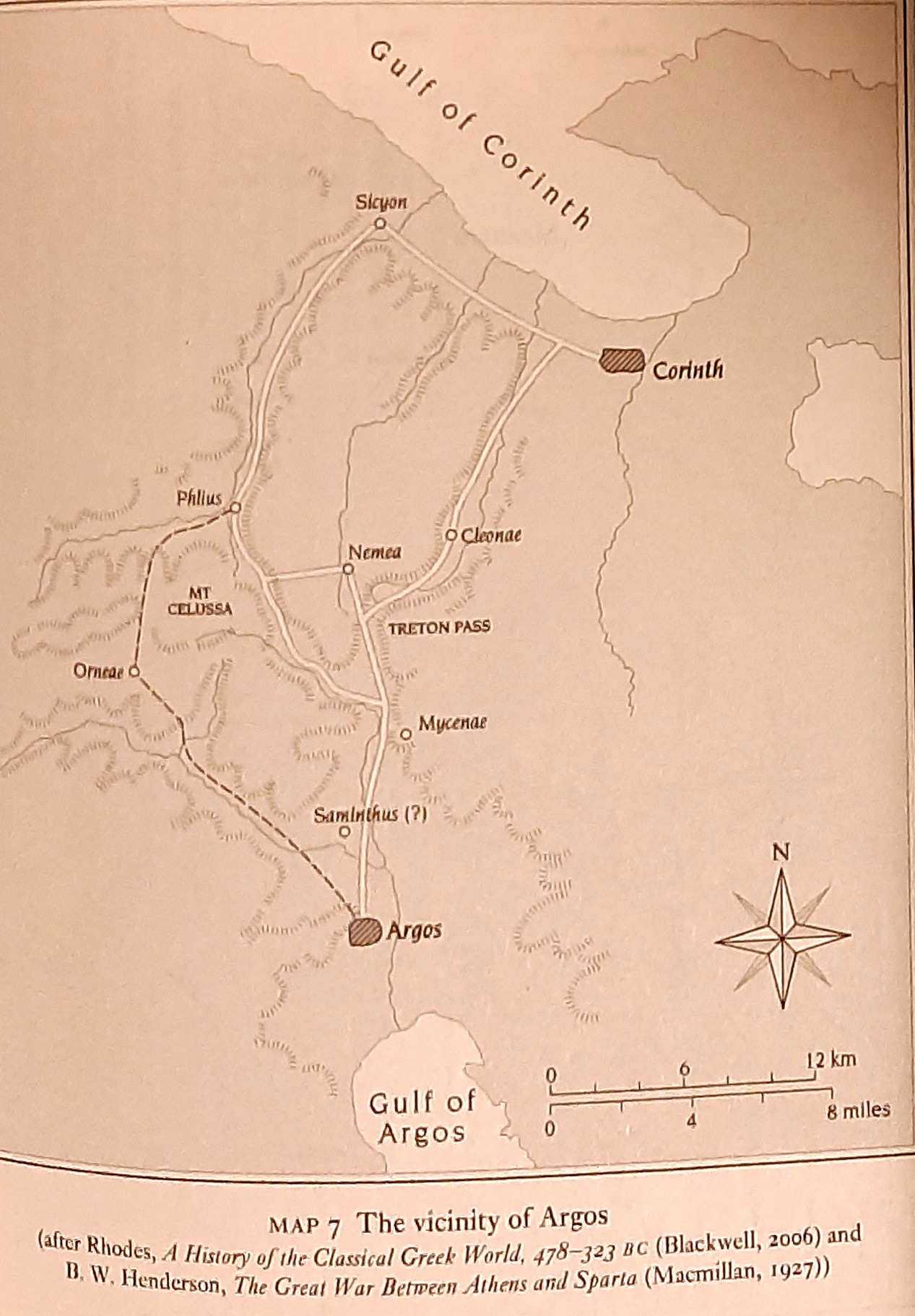

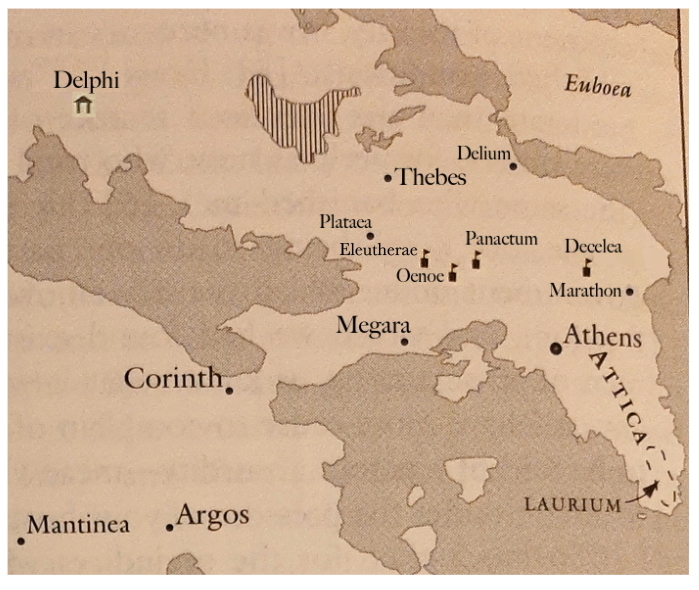

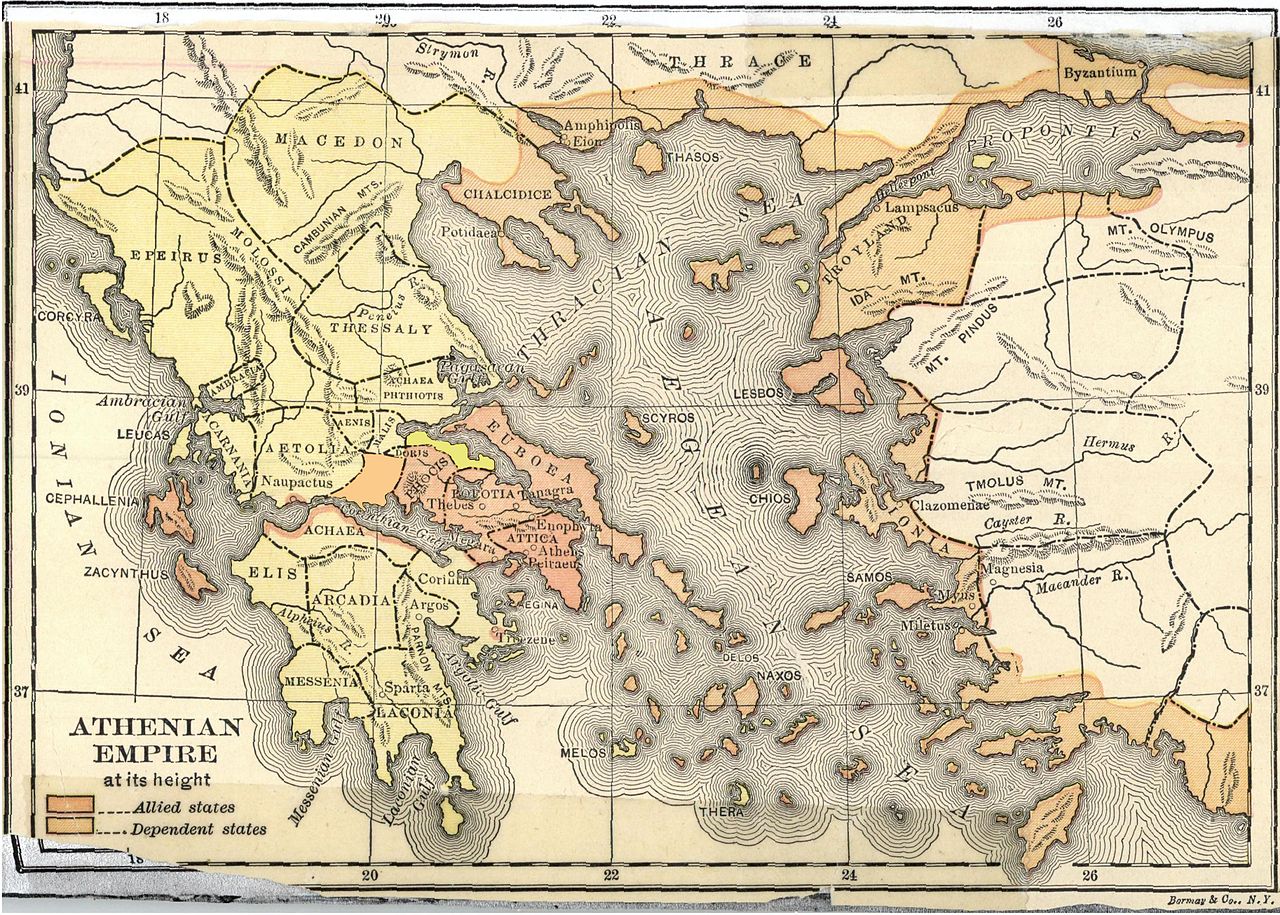

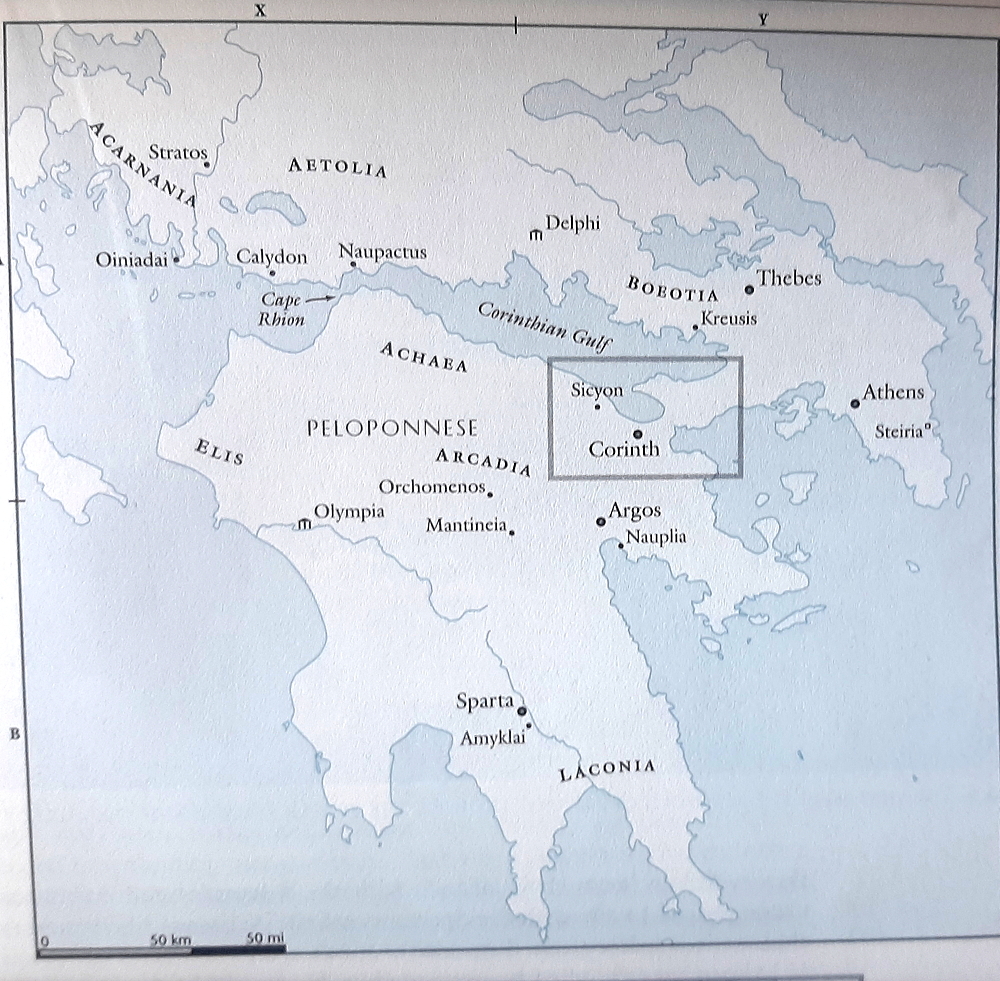

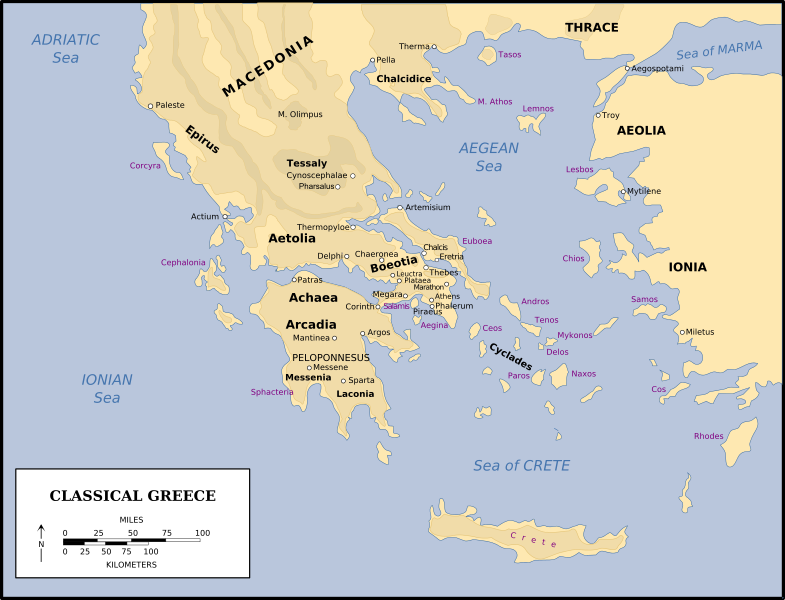

The Greek world of this period was composed of many lesser leagues, alliances, and kingdoms, such as the north-western state of Epirus, led by the hotspur Pyrrhus who invaded Italy in 280; the Sicilian metropolis of Syracuse, ruled since 275 by the wily King Hiero II of Syracuse, one of Pyrrhus’ successors; the resurgent Spartans, ruled by Leonidas II (254-235) and then Cleomenes III (235-222); the Achaean (Achaian) League of federated Peloponnesian poleis, led since 245 by the heroic Aratus of Sicyon, and their bitter enemy the Aitolian (Aetolian) league of the Corinthian Gulf, which by 260 controlled seven seats on the foundational religious Amphictyonic Council at Delphi, and nine by 250 including the secretaryship.[1]

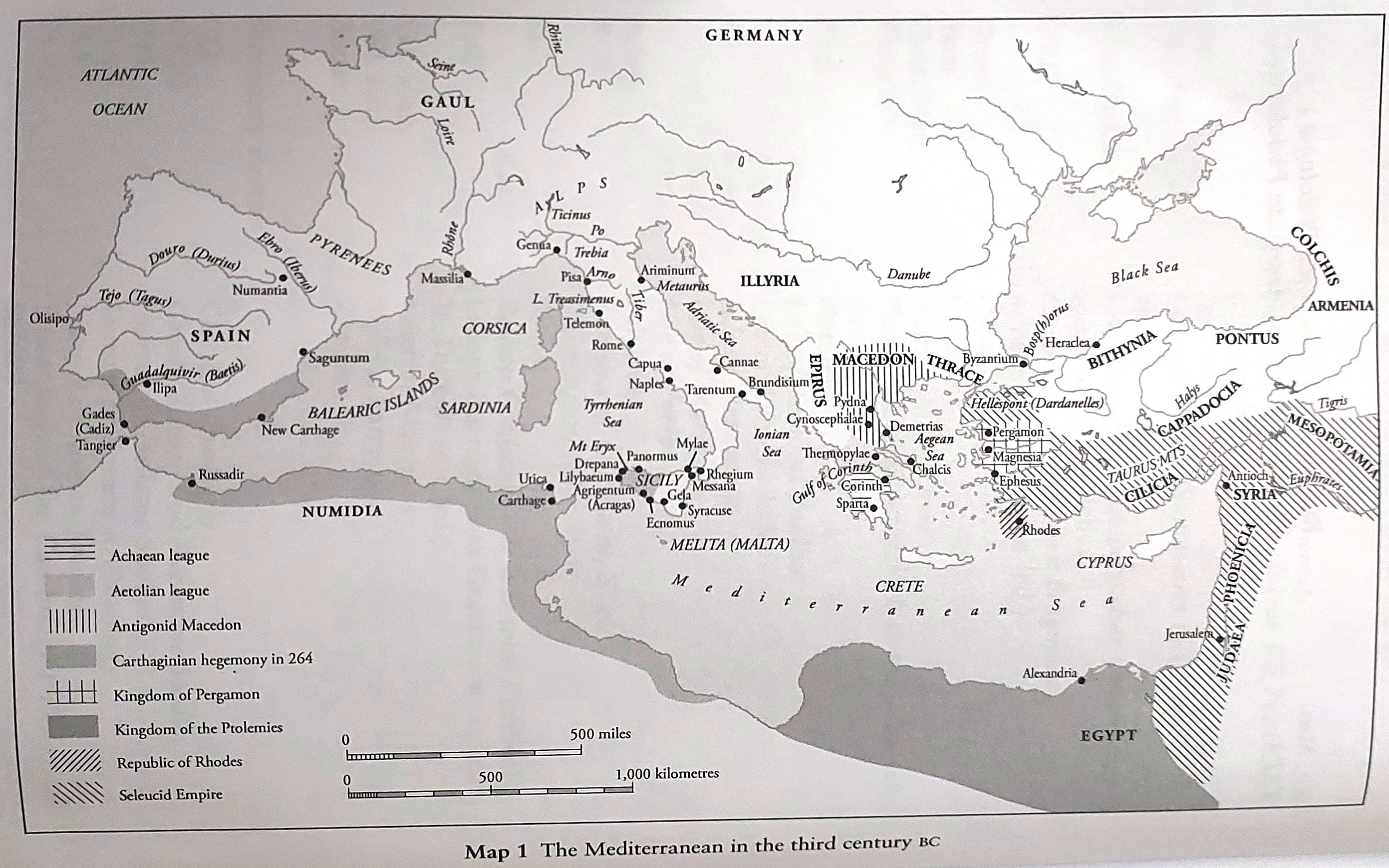

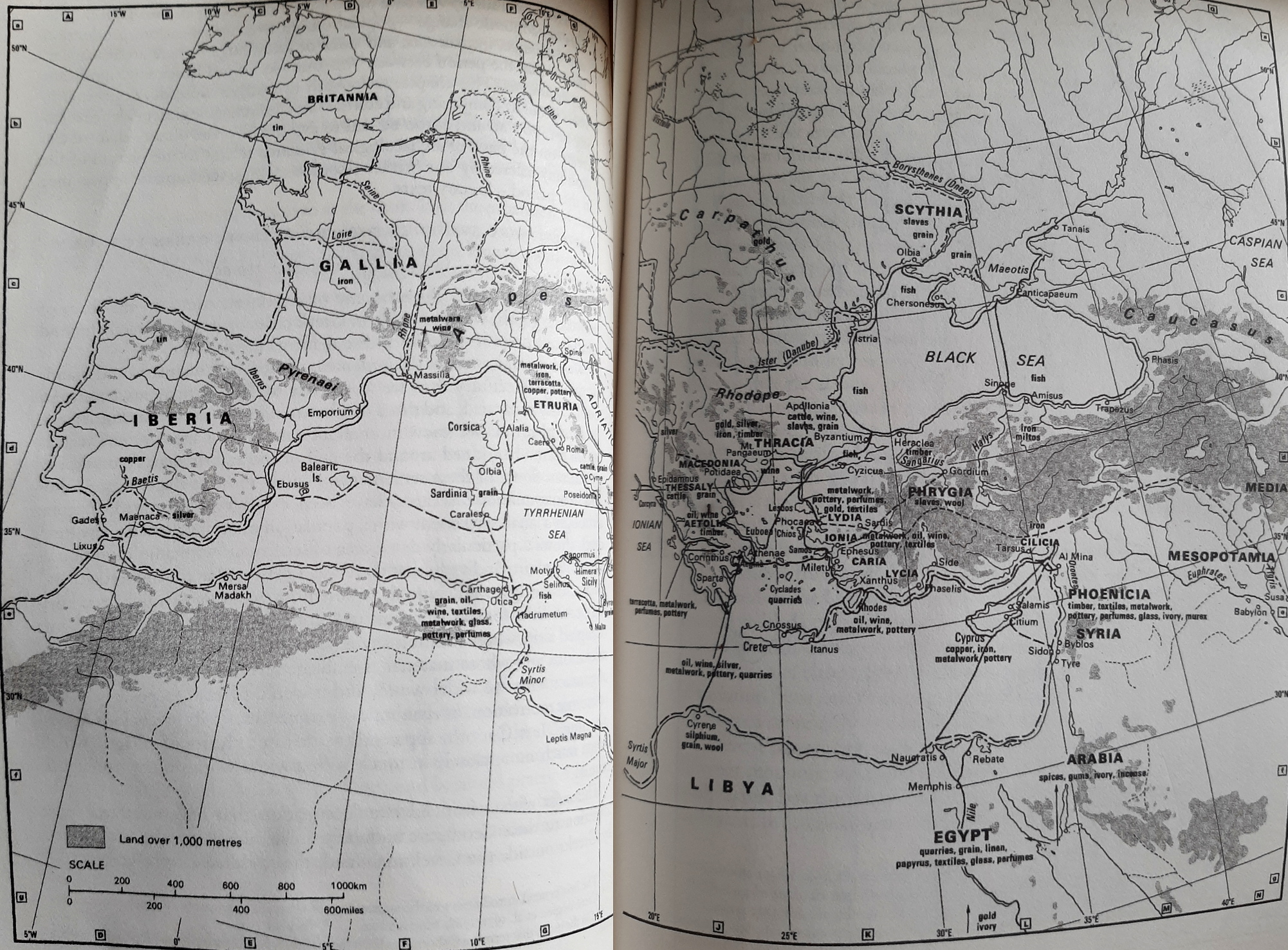

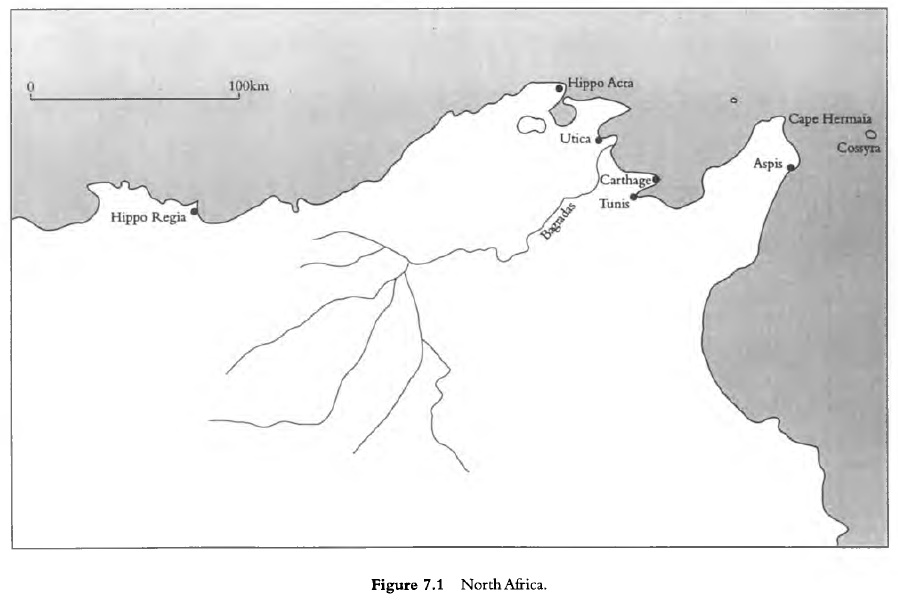

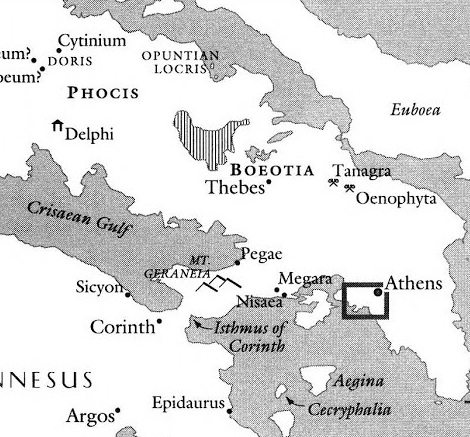

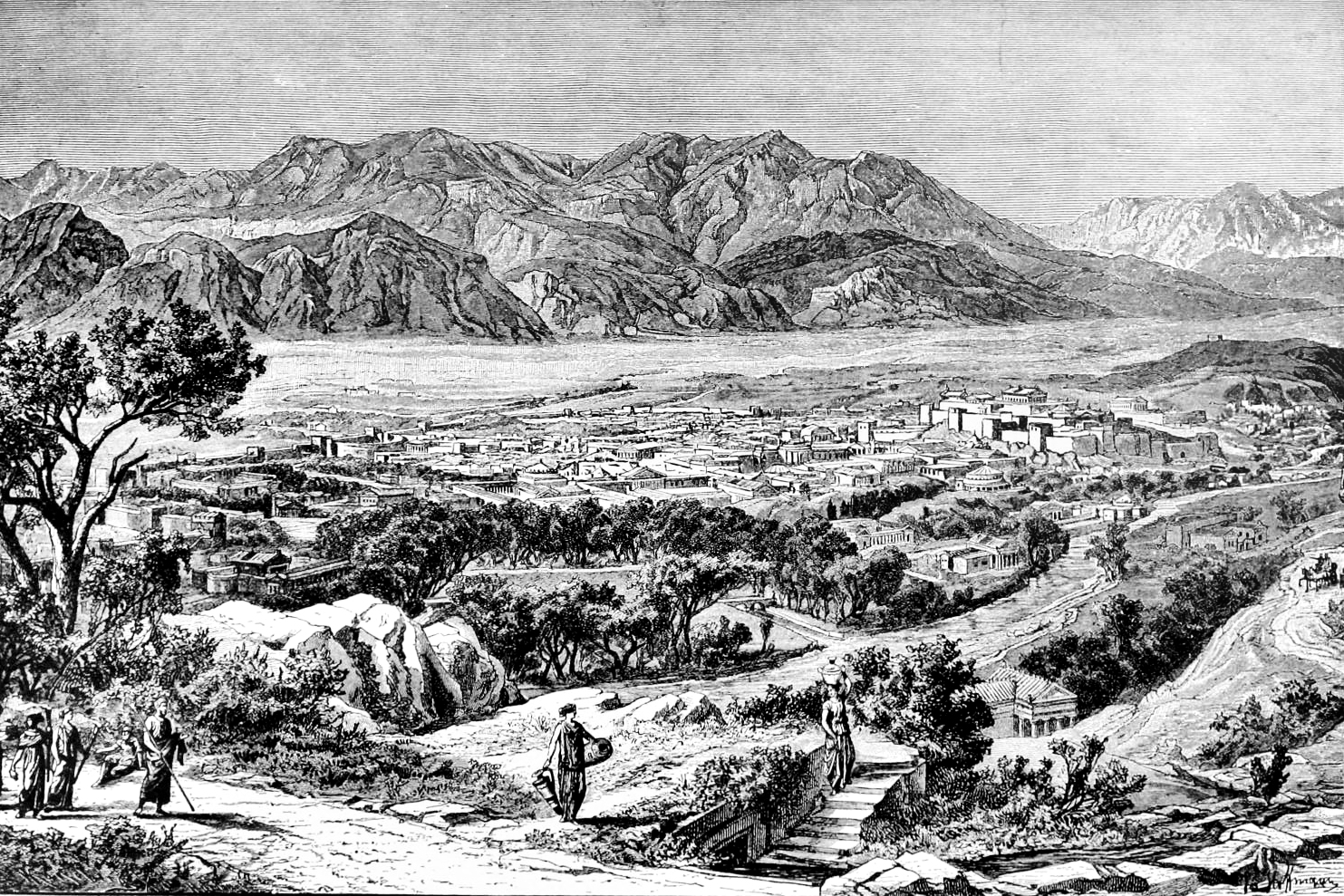

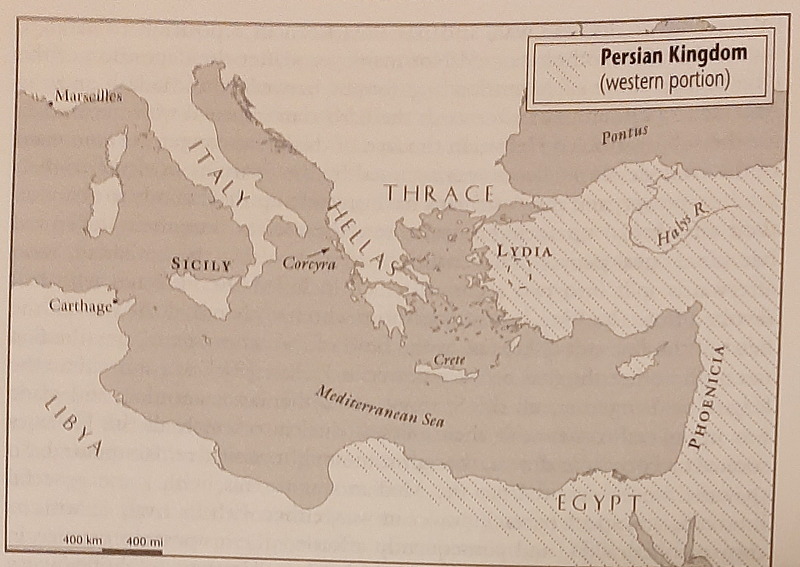

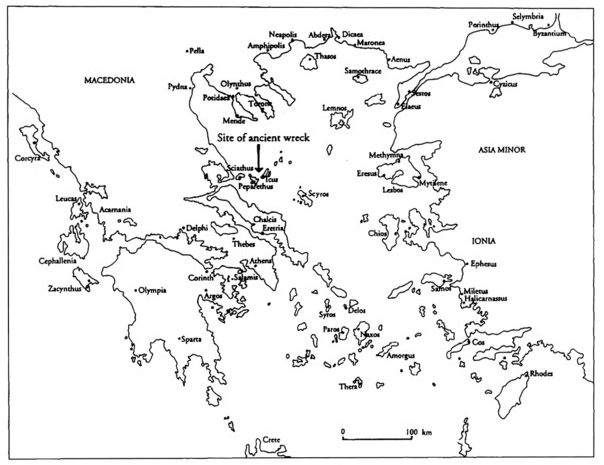

The Mediterranean world in the 3rd century BC, from Nathan Rosenstein, Rome and the Mediterranean, 290 to 146 BC (2012)

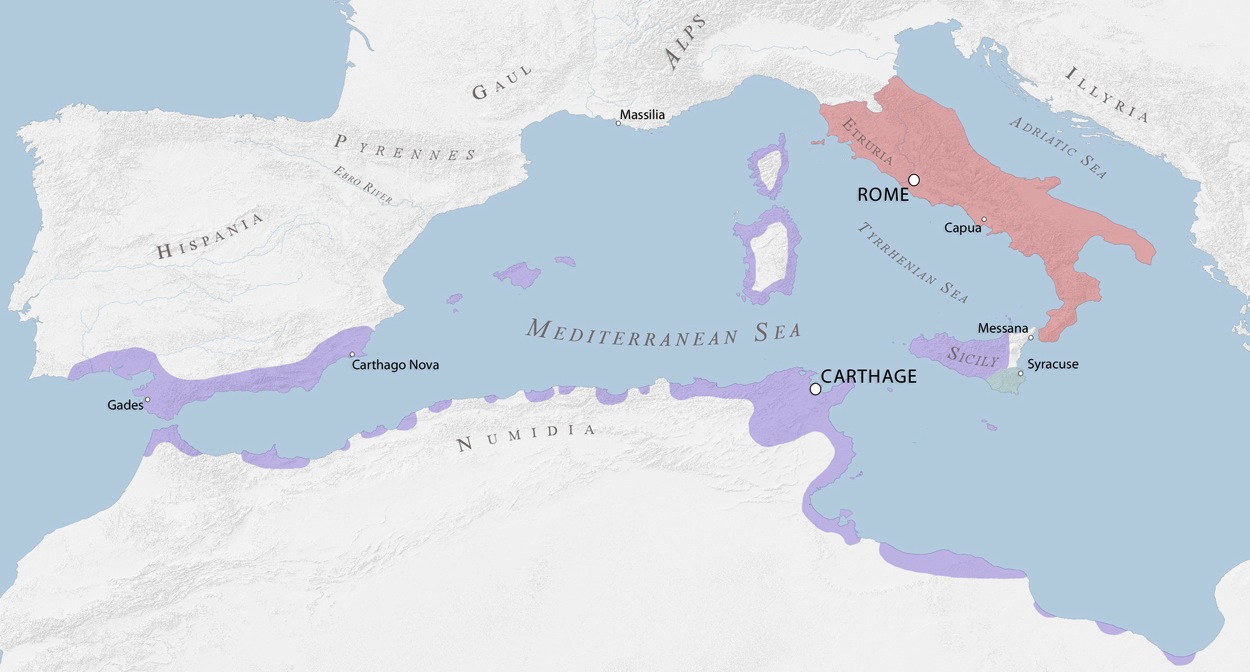

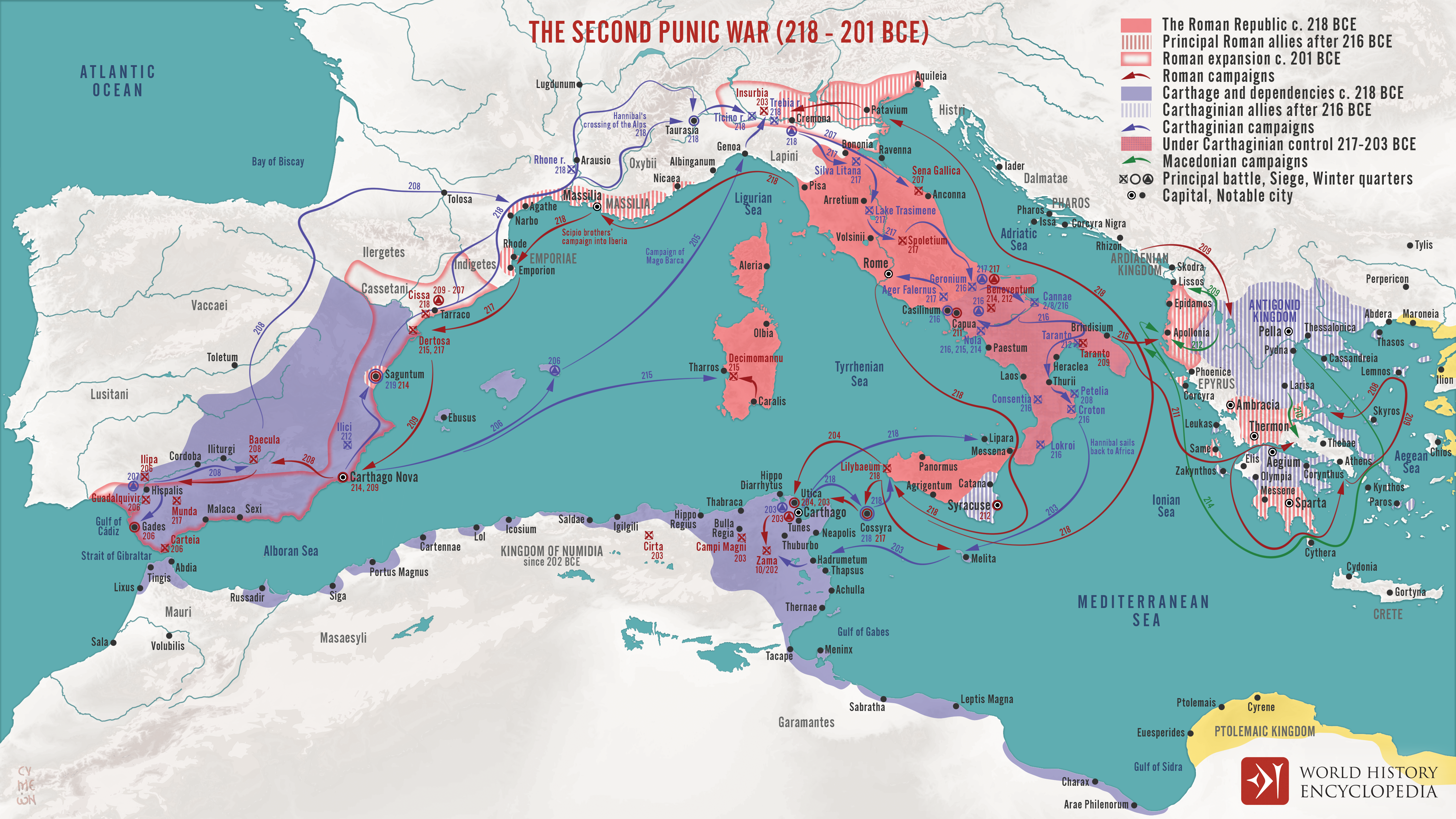

While the ‘funeral games’ between the diadochi were ongoing in the east, in the western Mediterranean there were but two powers, not yet contending for dominance, but both increasing in wealth and influence: The Roman Republic, approaching its 500th anniversary, and the ancient Phoenician city-state of Carthage.

After the defeat of Pyrrhus, the Republic’s interests and influence were beginning to expand beyond the Italian peninsula.[2] The major competitor for Rome’s westward expansion was Carthage, and it would take more than 60 years (264-202) to overcome the powerful Liby-Phoenician city-state with its Iberian, North African, Sardinian, Corsican and Sicilian colonies. But the conflict with Carthage was not inevitable, and the decision by the Romans to march into Sicily came only at the end of a centuries long struggle between Carthage and Syracuse for control of the island. This post compiles the fragmentary historical narratives of the period to demonstrate that the Romans arrived late to the Sicilian game, but, by cultivating sea power, went on to win it.

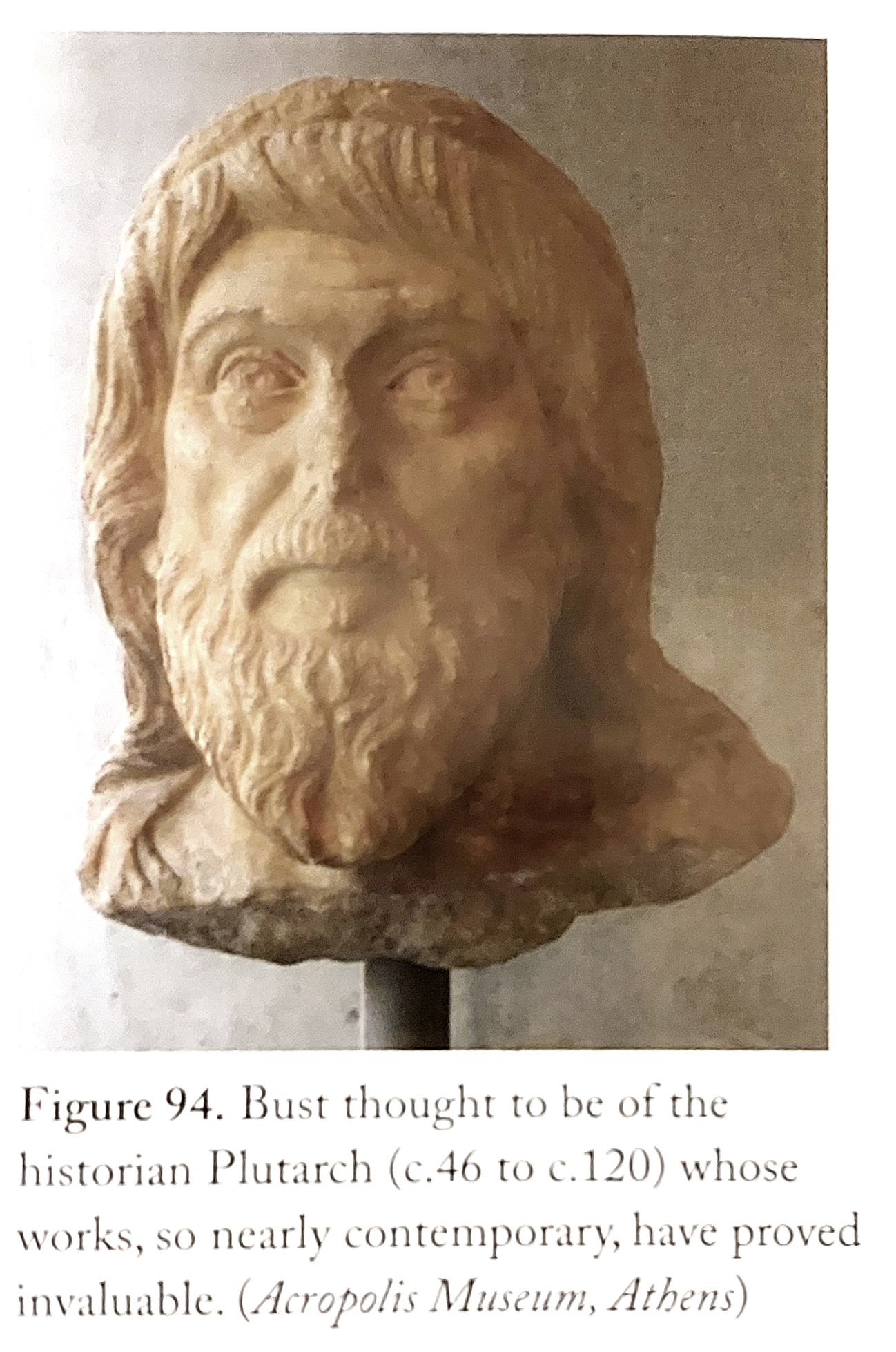

A word on ancient sources: Titus Livius’ Ab Urbe Condita, books 11-20 are lost, with books 15 (272-265), 16 (264-261), 17 (260-256), 18 (256-252) and 19 (251-241) having covered the period of the First Punic War; four or five books compared with the nine books, 21-30, of the Hannibalic war,[3] although the 2nd century AD chronicler Florus,[4] the 4th century historian Eutropius,[5] the early 5th century Christian apologist Orosius,[6] and later the Byzantine chronicler Zonaras, all had access to various First Punic War material, including the traditions of Livy and Cassius Dio, and thus their breviarium or epitomes are of value for at least supplementing the Polybian material.[7] It is known that one of Livy’s key sources was the historian Claudius Quadrigarius, whose work covered the period of the 4th and 3rd centuries, including the First Punic War, but the latter’s work is now entirely lost besides some fragmentary quotations.[8] The same is true for the great Sicilian historian Timaeus of Tauromenium, whose detailed history of Sicily covered the period up to the beginning of the First Punic War but is now totally lost except for its tradition preserved in Diodorus Siculus and Plutarch and a few fragments.

Polybius, Diodorus Siculus, Livy, Plutarch, Cassius Dio, Zonaras

The 2nd century BC Greek historian Polybius’ first book briefly chronicles the First Punic War, and is the most comprehensive if incomplete source. Polybius’ sources were the Sicilian historian Timaeus, the Greek historian and Carthaginian sympathizer Philinus of Acragas,[9] and the early Roman historian Fabius Pictor,[10] who all dealt with the various conflicts of the mid-3rd century BC.[11] The first century AD Alexandrian historian Appian wrote manuscripts covering various Roman wars, including the First Punic War, but only fragments survive. The Emperor Claudius later consolidated books on the Etruscans and Carthaginians in a museum in Alexandria, although once more this material has been lost.[12]

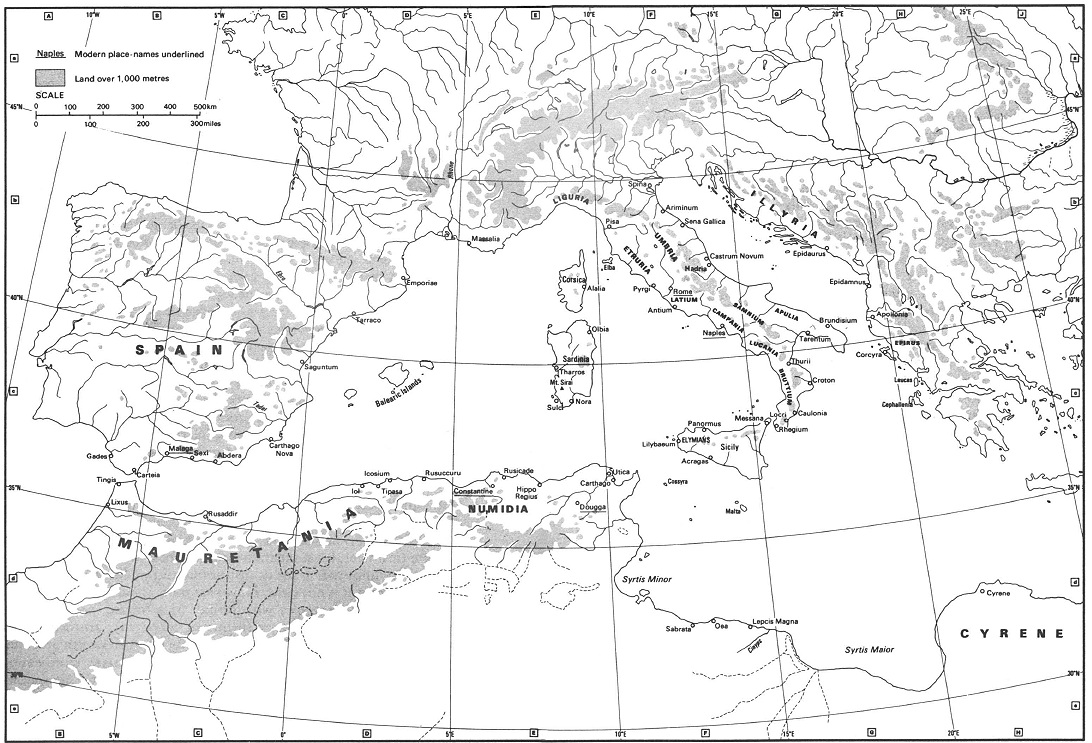

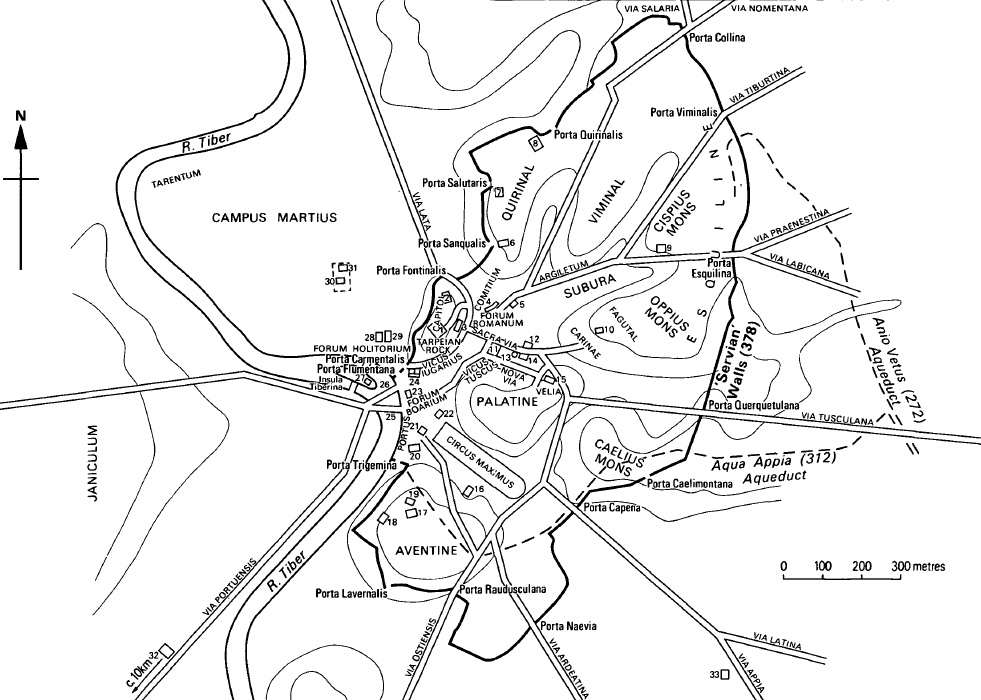

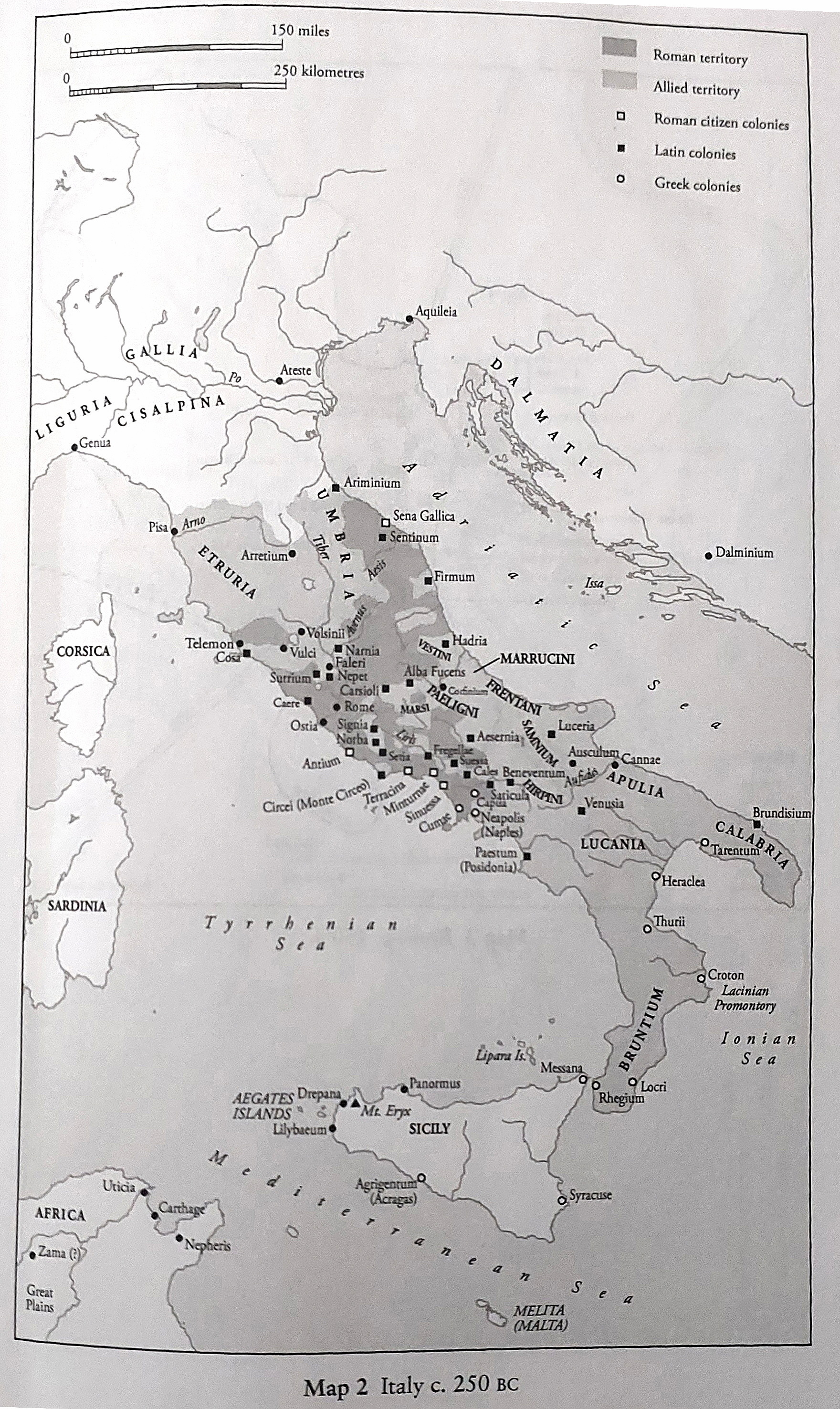

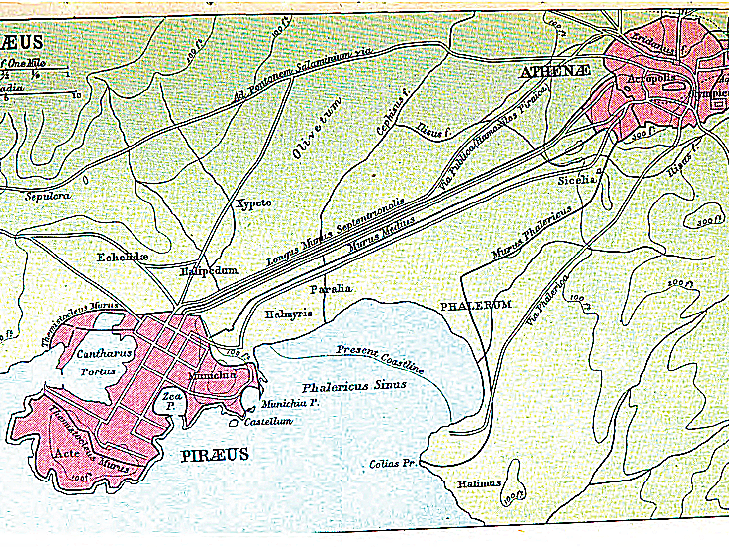

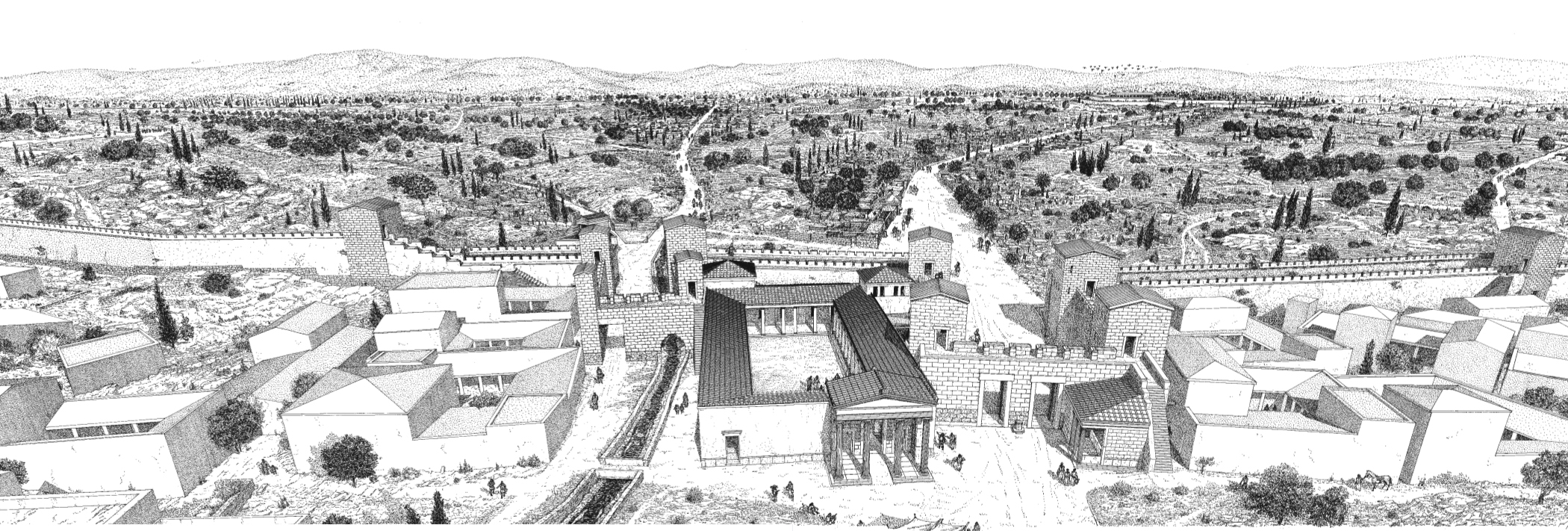

Western Europe in the Third Century BC, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008)

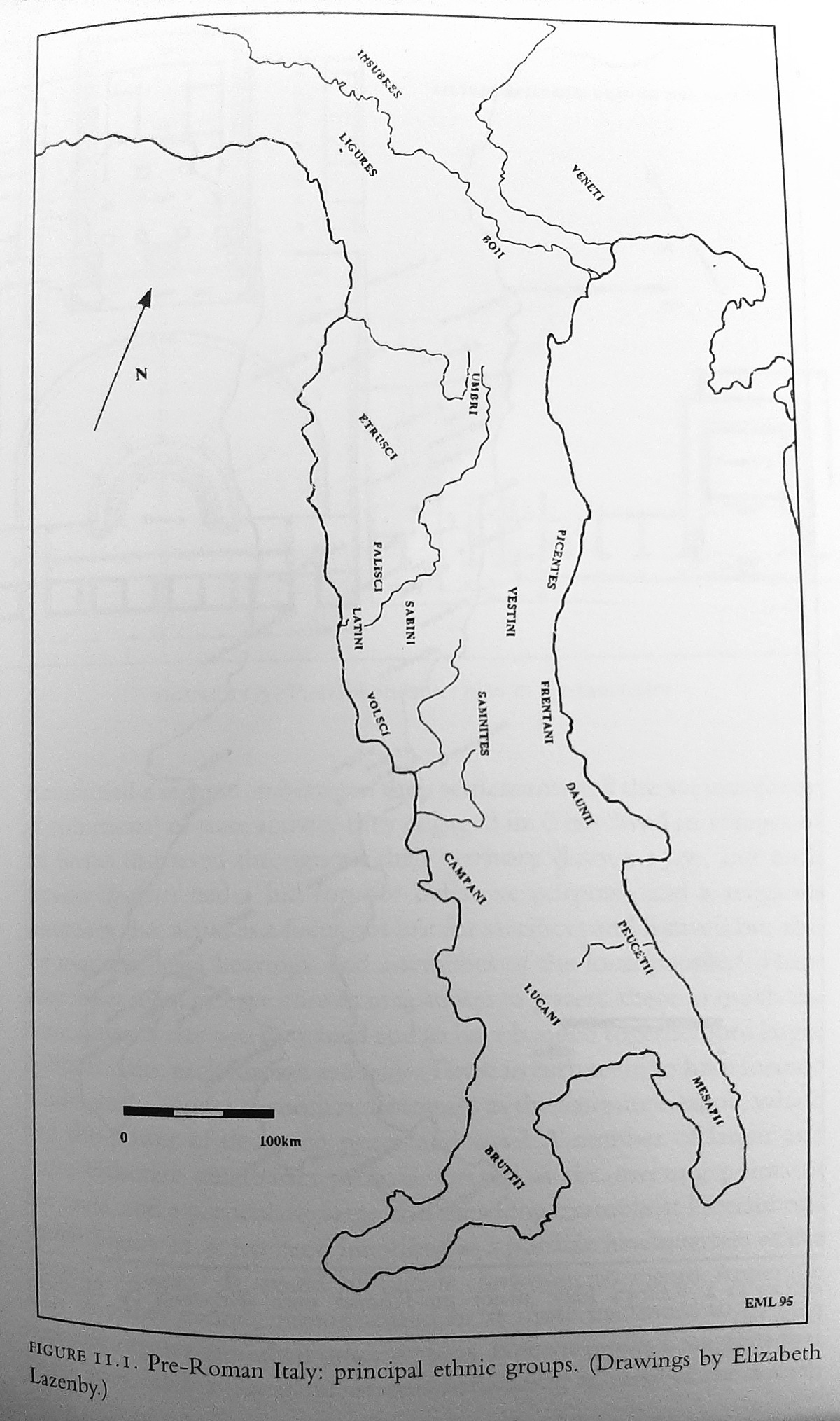

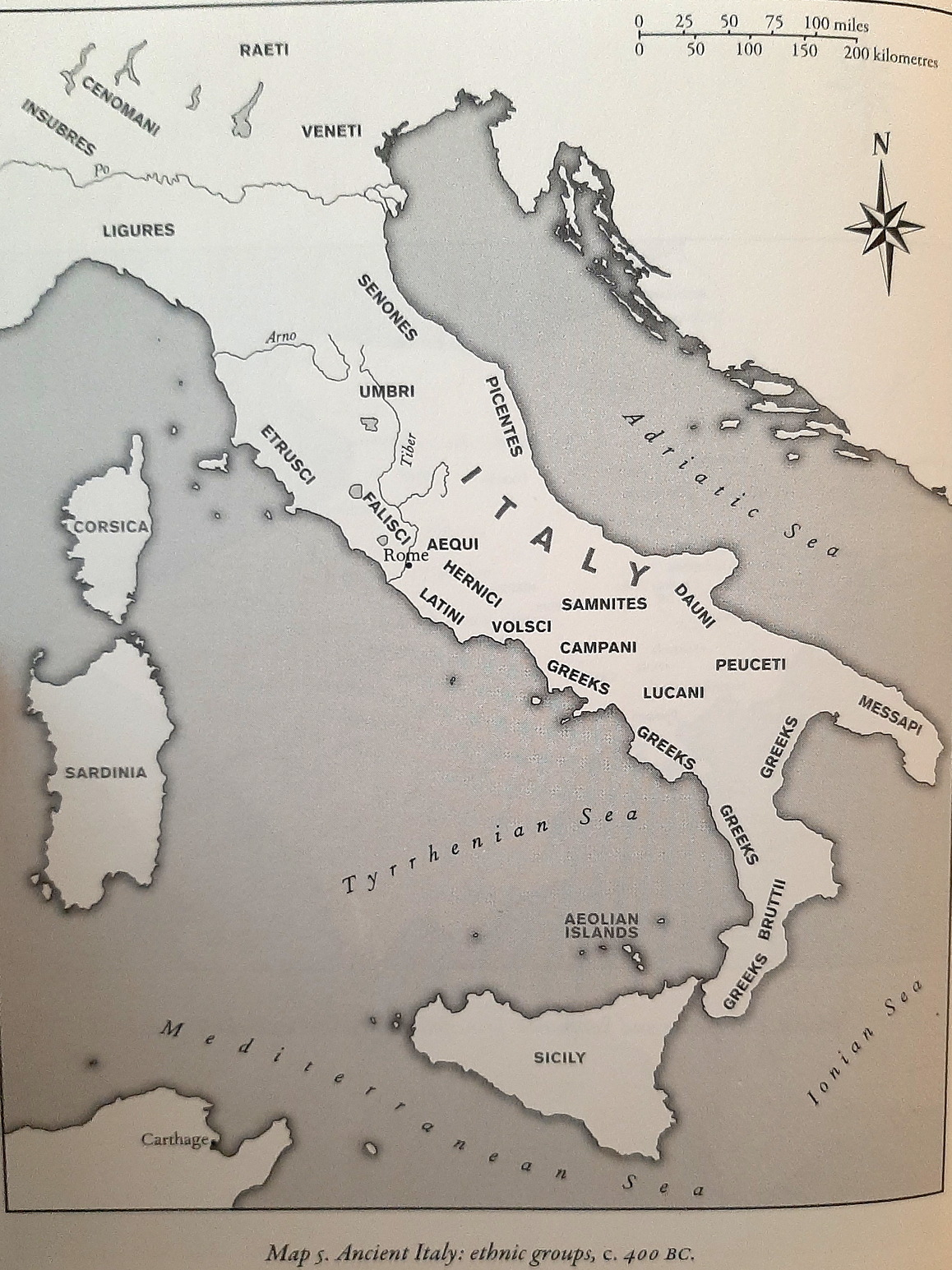

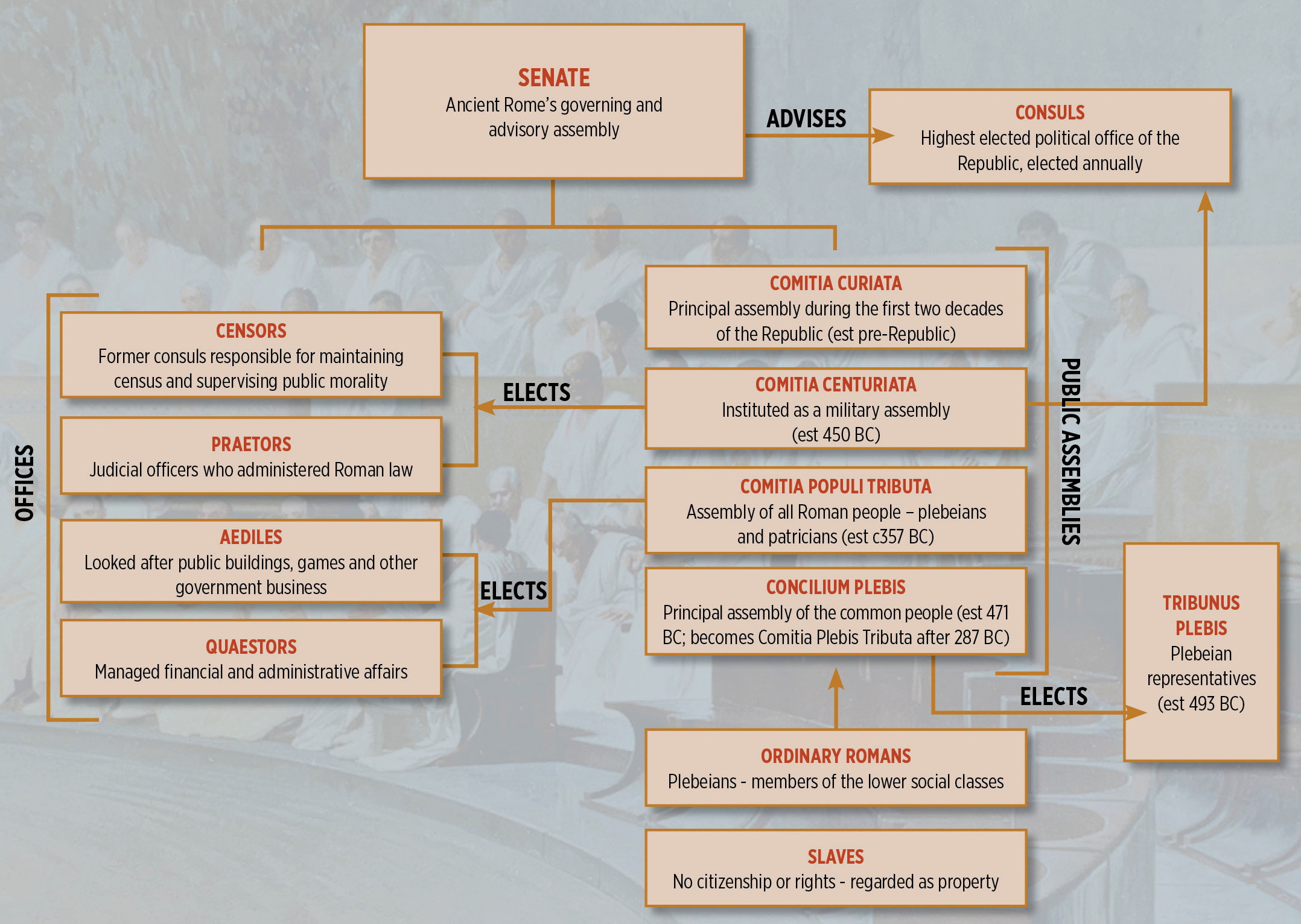

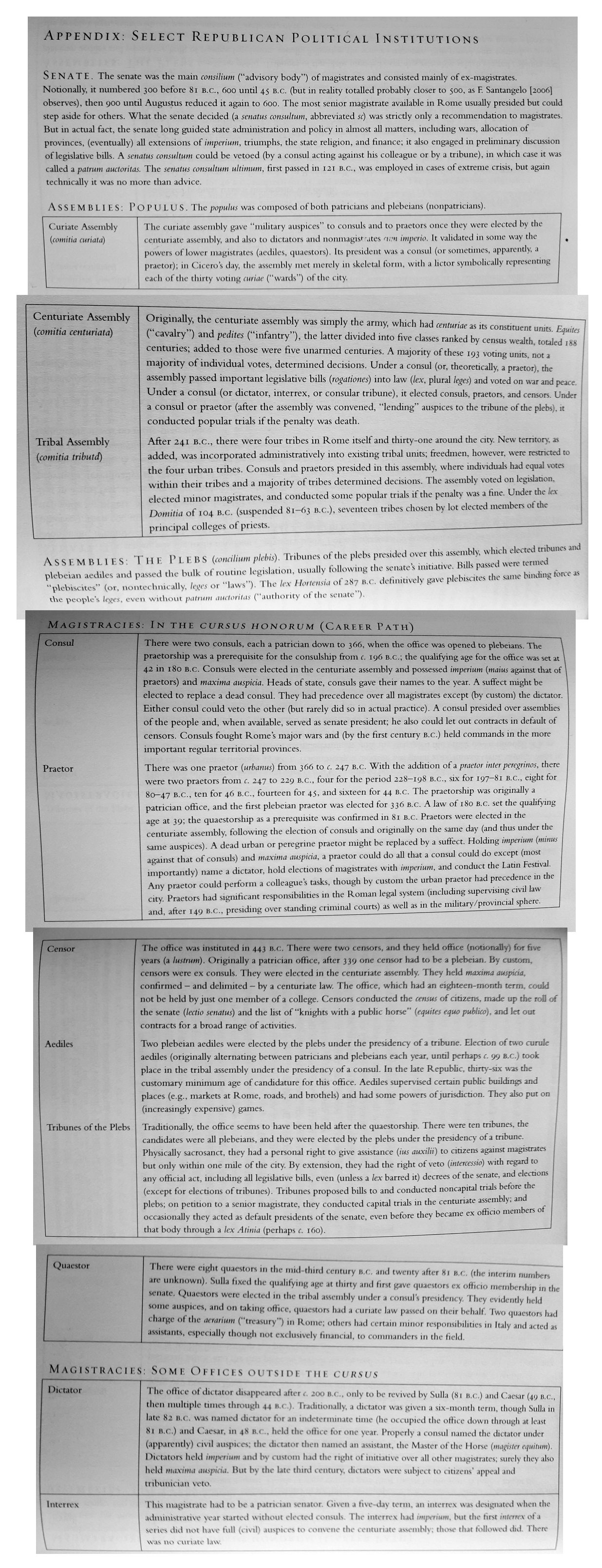

The Evolution of Roman State Institutions

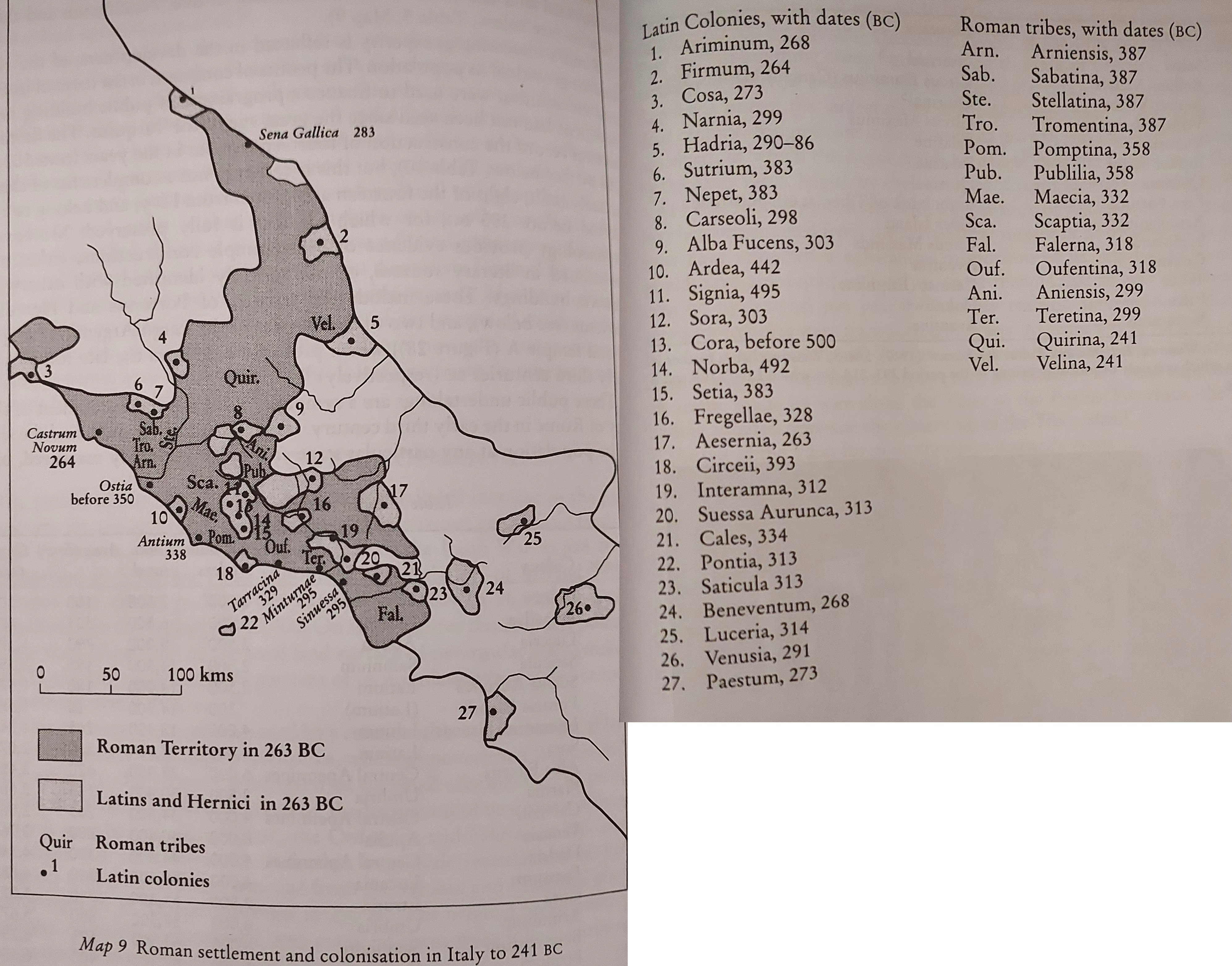

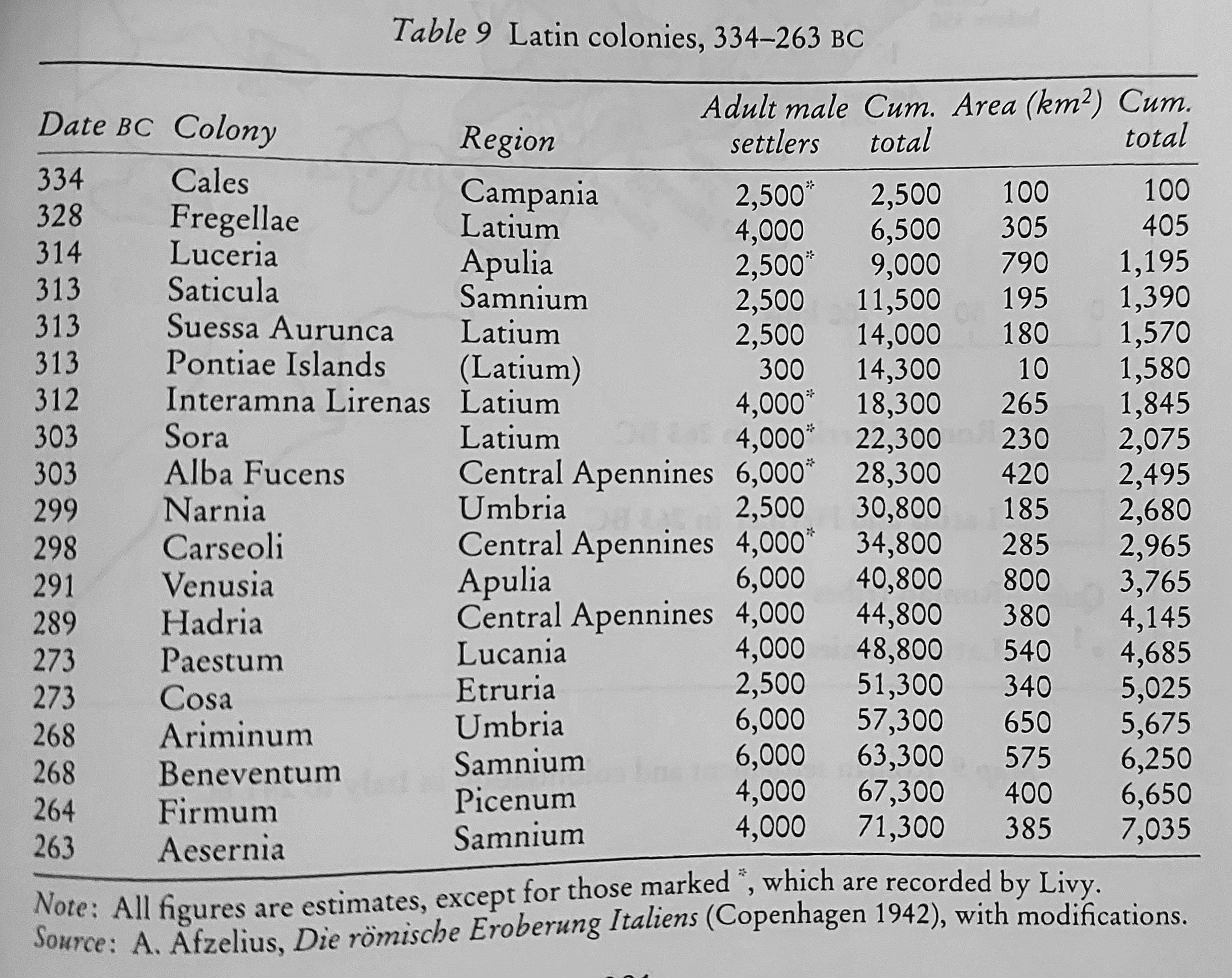

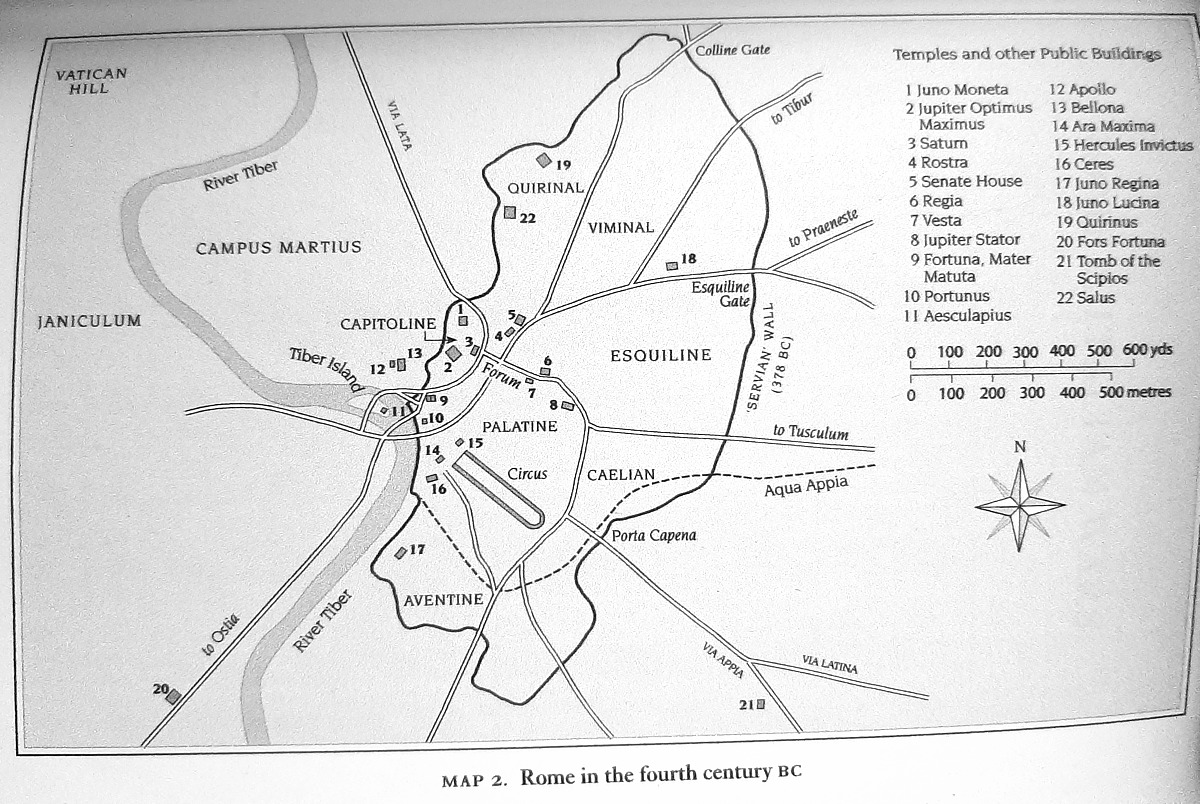

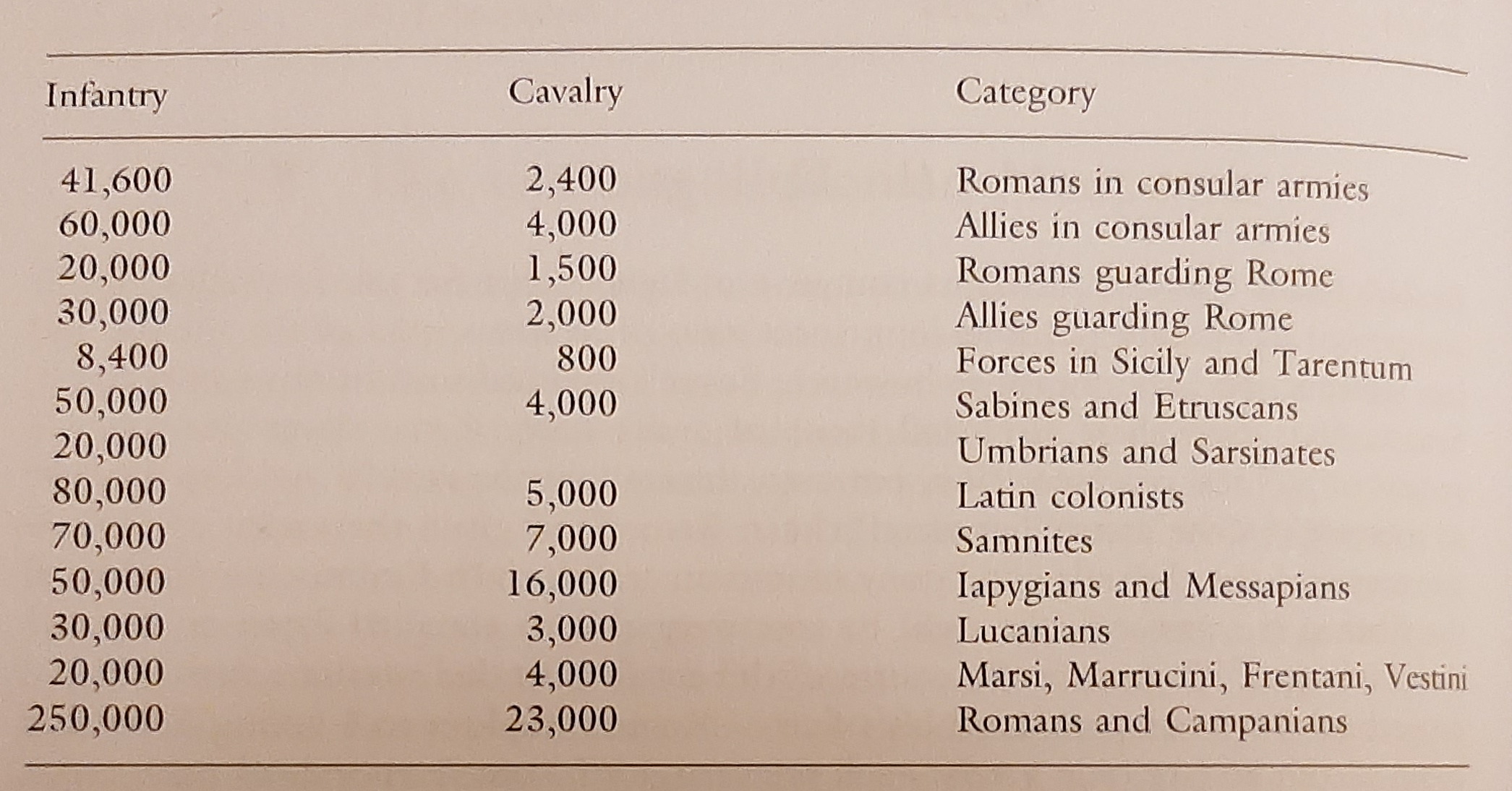

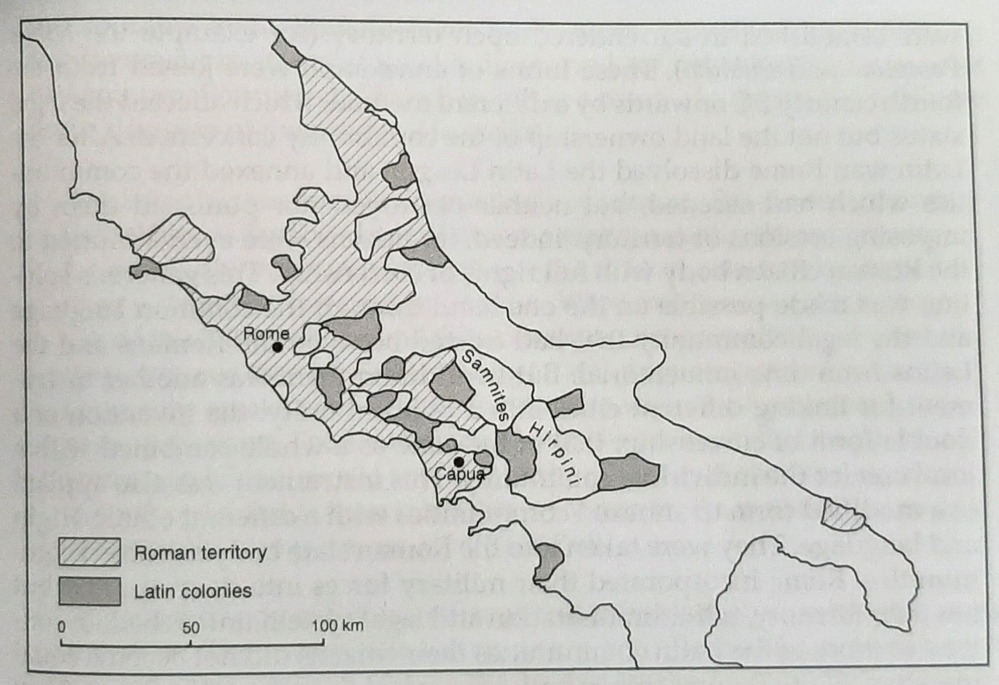

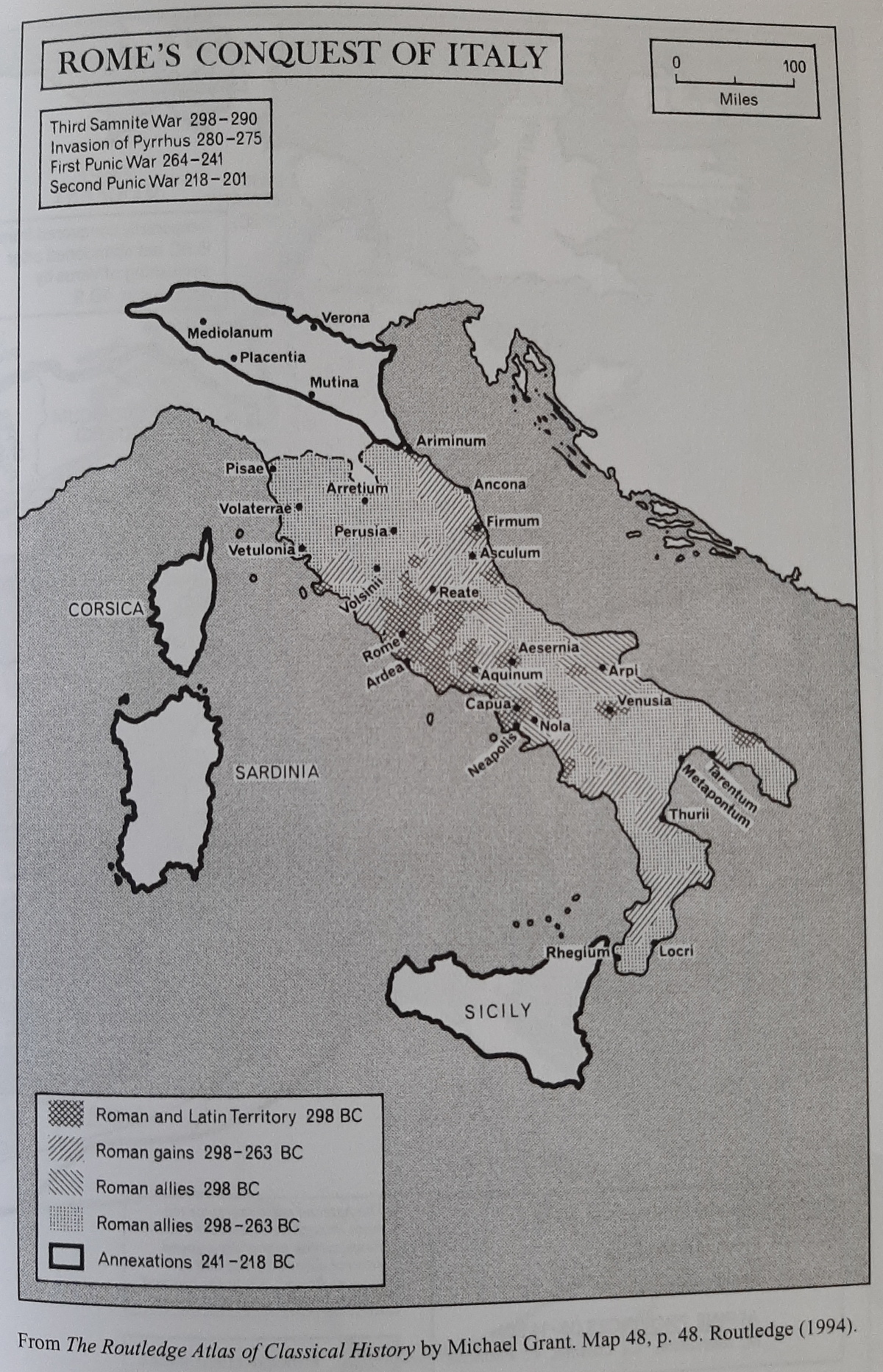

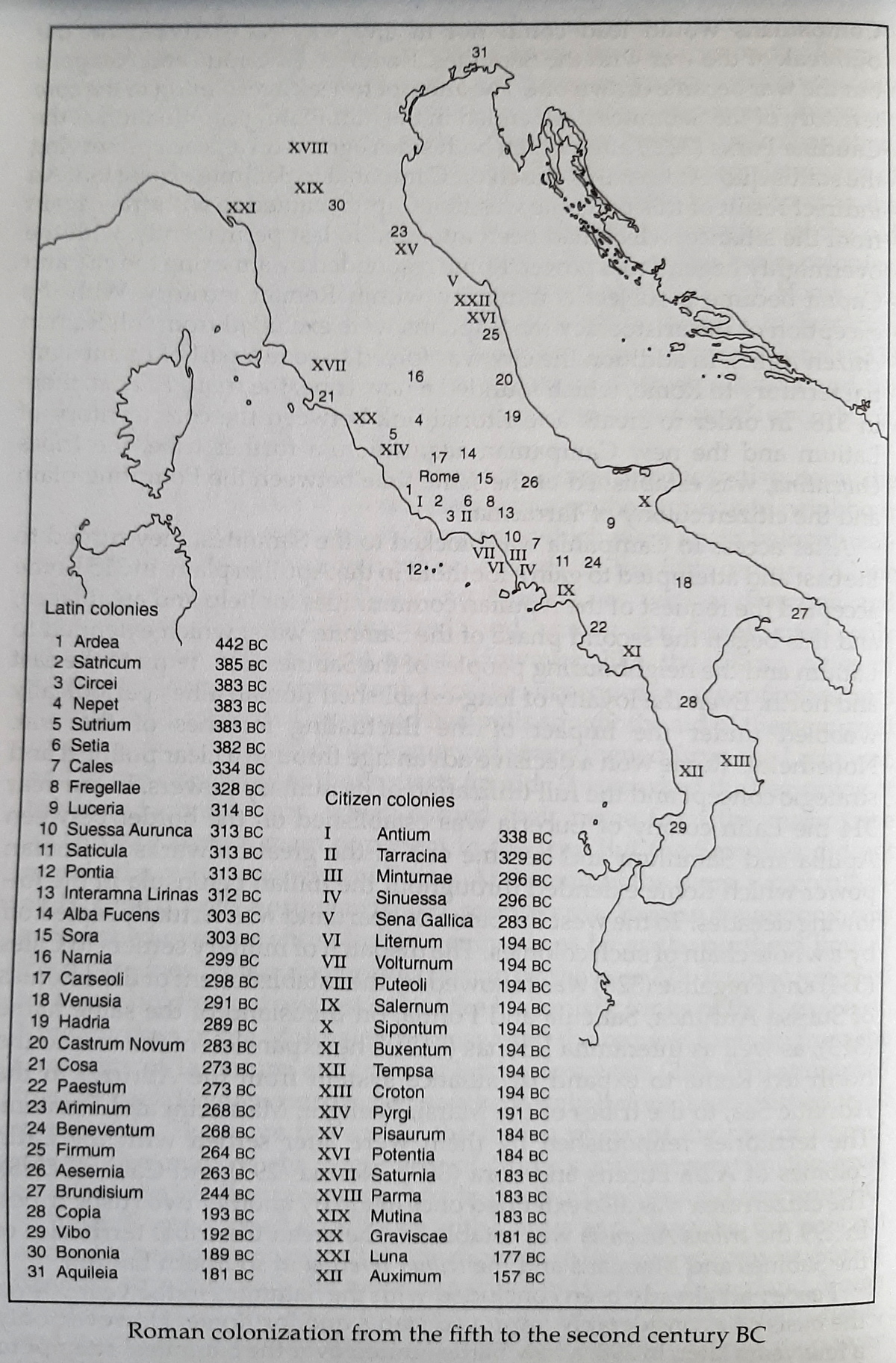

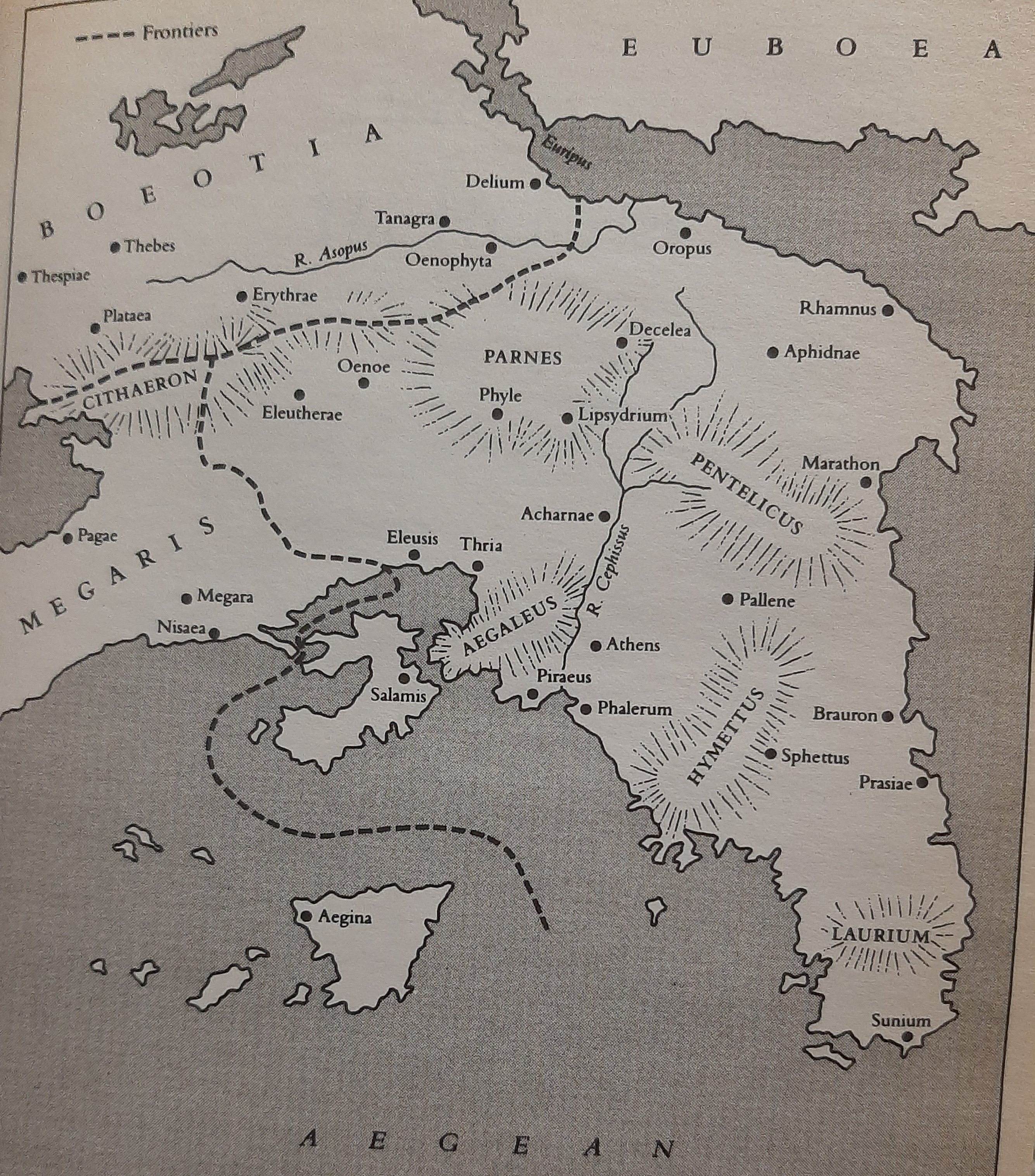

Roman and allied (socii) territory by the mid-3rd century encompassed all of Italy south of the Arno river, 50,000 square miles, with a population of about three million souls. This included the Latin socii nominis Latini, Latin territory not yet annexed directly, plus the 24 (and by 244, 26) Latin colonies Rome had established during the 4th and 3rd centuries.[13] In 509, the year of the expulsion of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the city of Rome controlled territory no greater than 822 km2 with a population of about 20,000-30,000, which was still the case by the end of the 5th century when Roman territory encompassed only 948 km2. At the start of the Samnite Wars (343-341, 326-304, 298-290) this territory had reached 5,525 km2.[14] 74 years later, after the Etruscan Wars (311-308, 302-292, 284-280) and the war with Pyrrhus (280-275), which was fought essentially over Roman expansion into southern Italy, by 264 the ager Romanus had expanded exponentially to encompass 26,805 km2, the whole of this area populated by about one million souls, of whom 200,000-300,000 lived in Rome itself.[15]

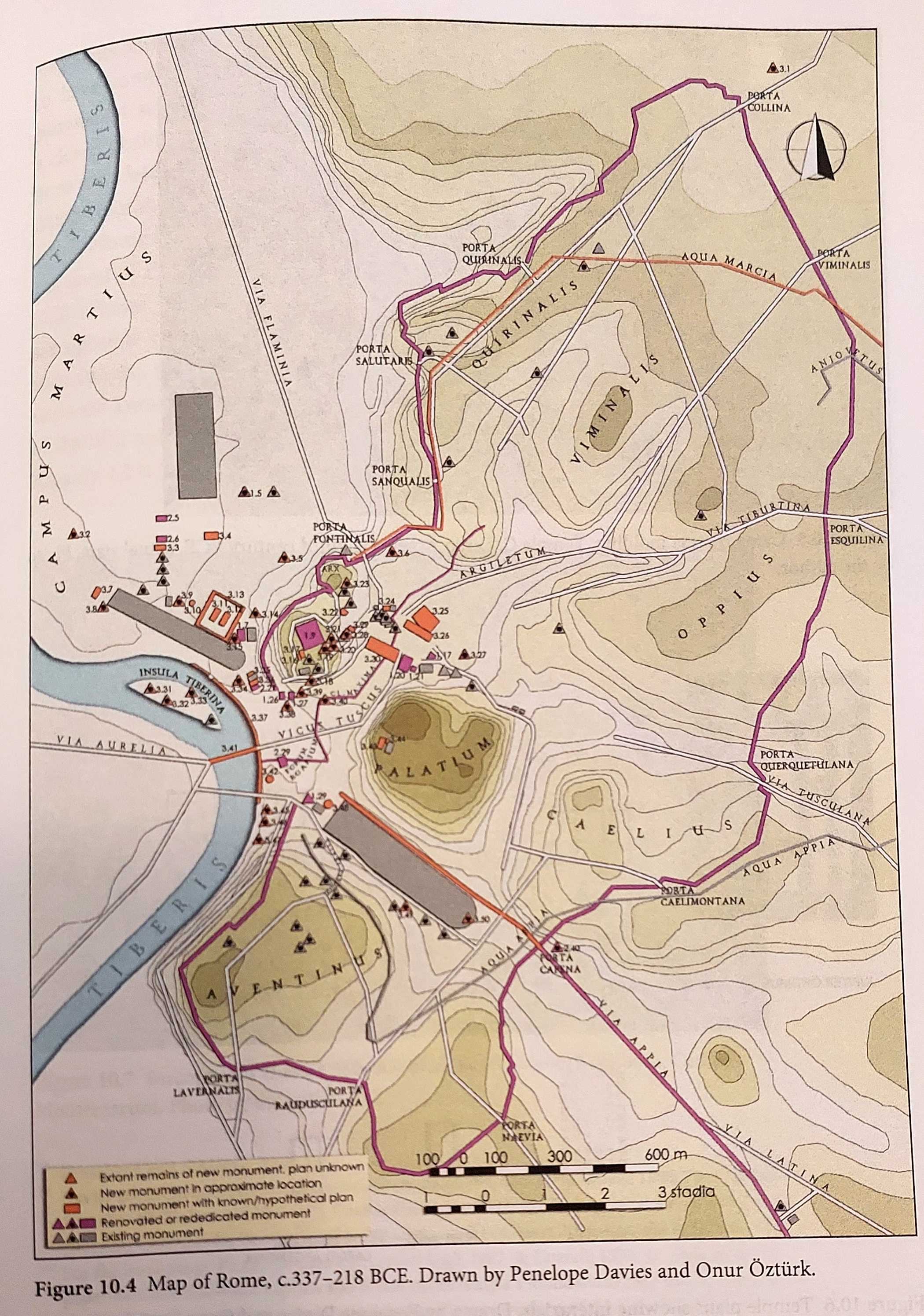

Roman colonies by 263, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008)

Roman and Latin territory, Allies and colonies, from T. J. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (1995)

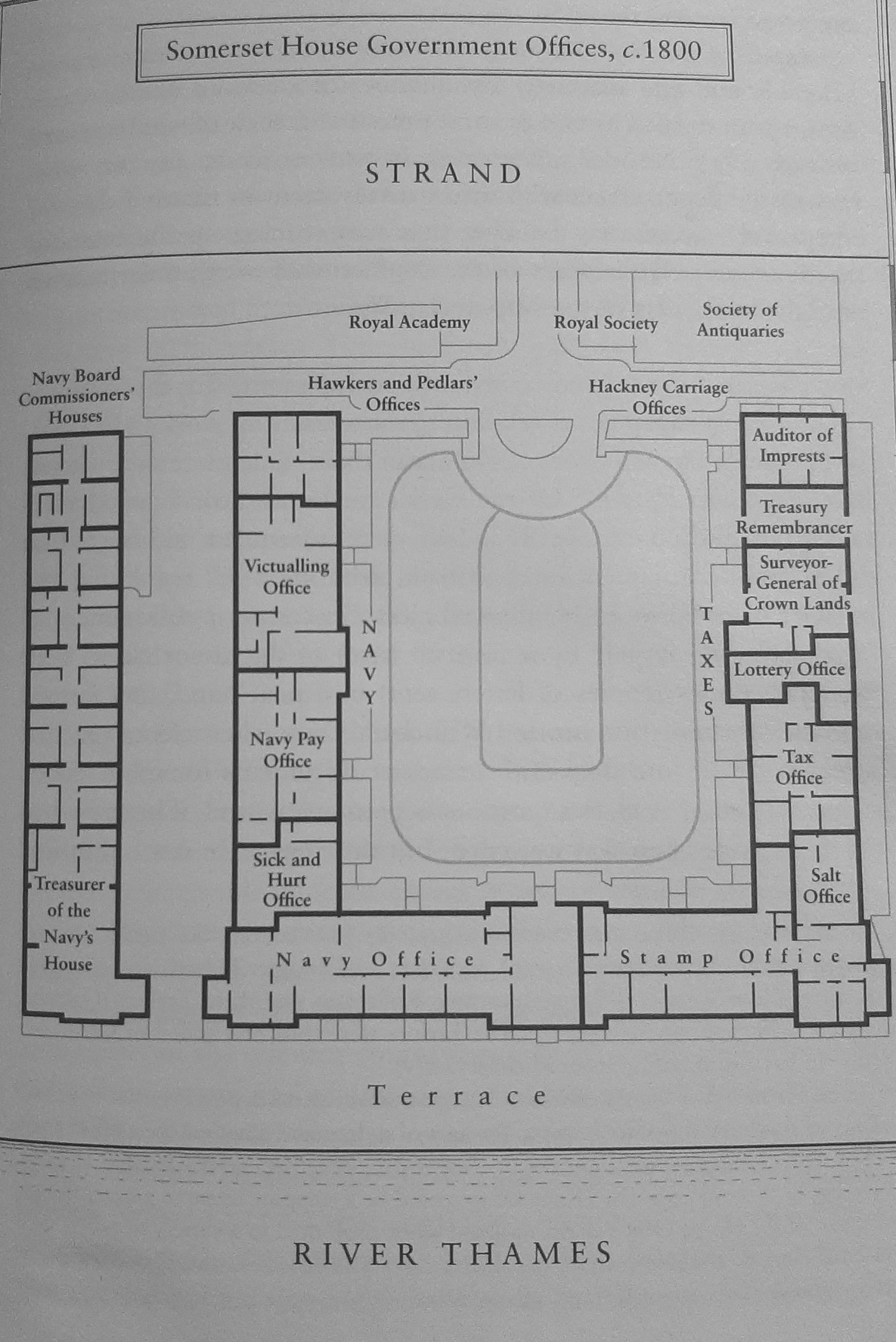

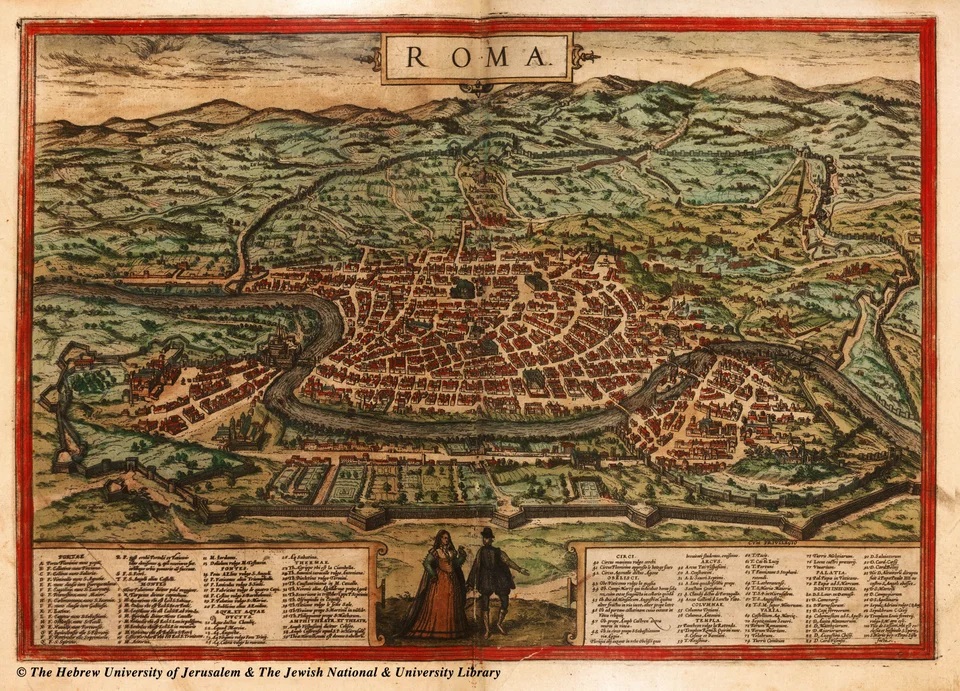

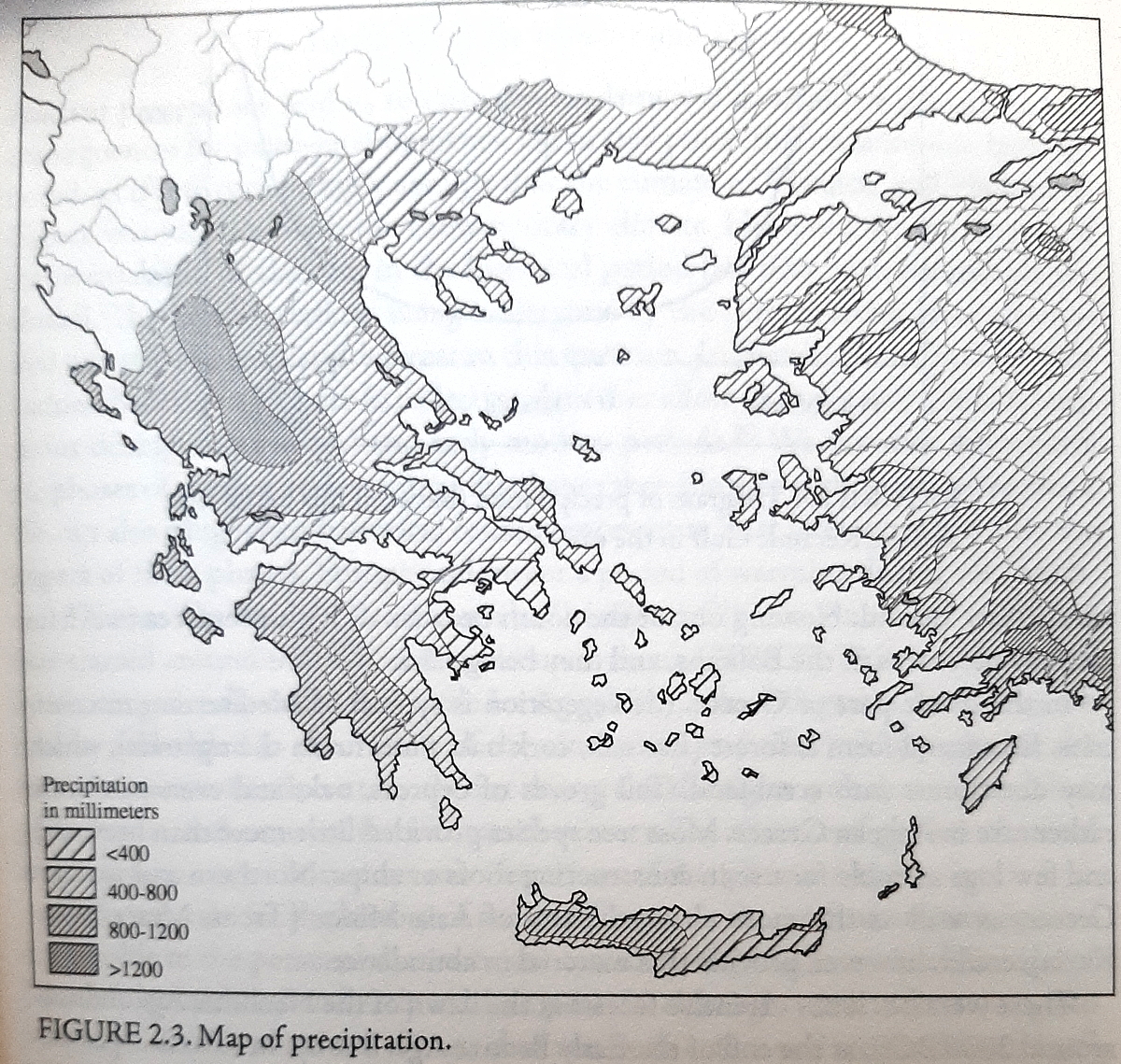

Indeed, the city of Rome in the 3rd century was a bustling metropolis, if archaic and underdeveloped, with trade connections throughout Italy and around the Mediterranean.[16] The first aqueduct was commissioned by the reforming populist Appius Claudius Caecus in 312, as was the famous Via Appia south-running highway to Capua of his name,[17] and Manius Curius Dentatus used the plunder from the war with Pyrrhus to build the Aqua Anio Vetus in 272.[18] A city-wide night watch was introduced between 290-287, demonstrating the increasing organization of Rome’s urban affairs by the praetor.[19] The first Roman coins were issued in 326.[20] Although Italy produced significant quantities of vegetables,[21] fruits, nuts, olives, fish, salt, game, wool, timber, charcoal,[22] stone, clay and pottery, including amphoras for wine and oil,[23] there was a perpetual shortage of grain,[24] making access to Sicilian and Egyptian grain supplies vital.

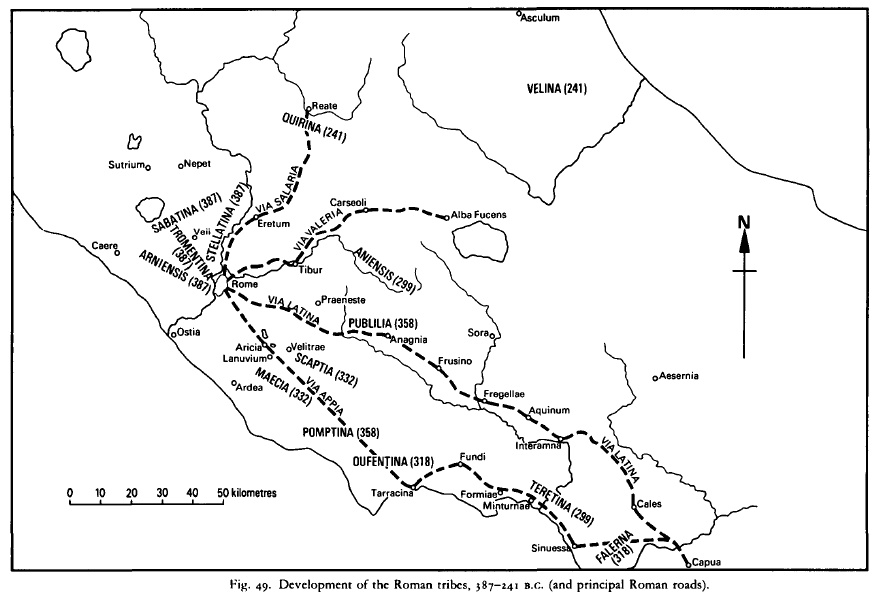

Roman roads by the mid-3rd century, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 7, part 2 (2008)

Mediterranean trade c. 500 BC, from The Cambridge Economic History of the Greco-Roman World, ed., Walter Scheidel et al (2014)

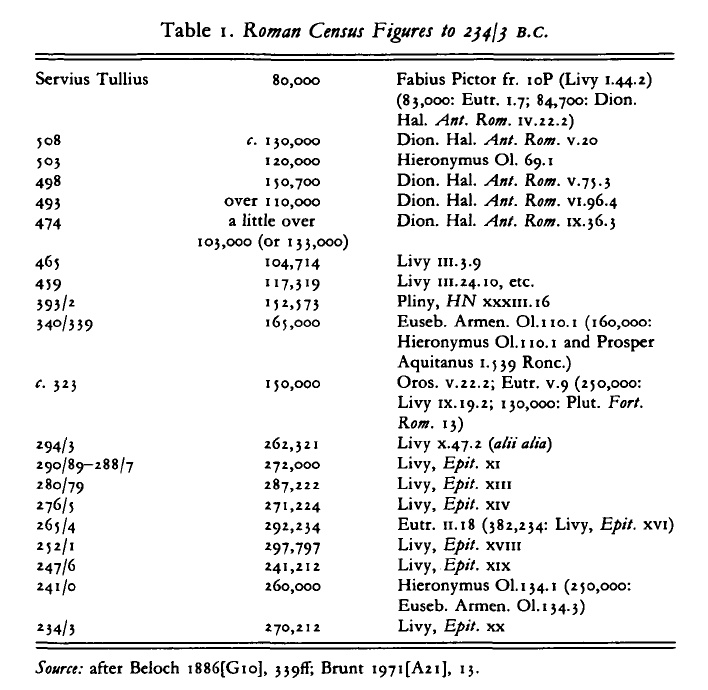

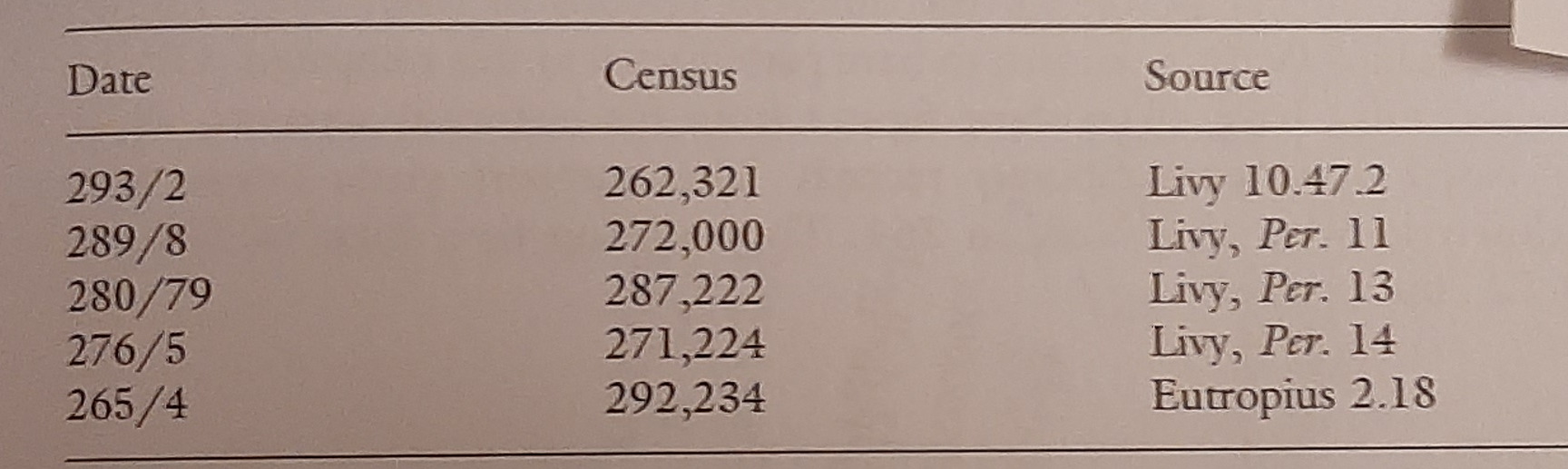

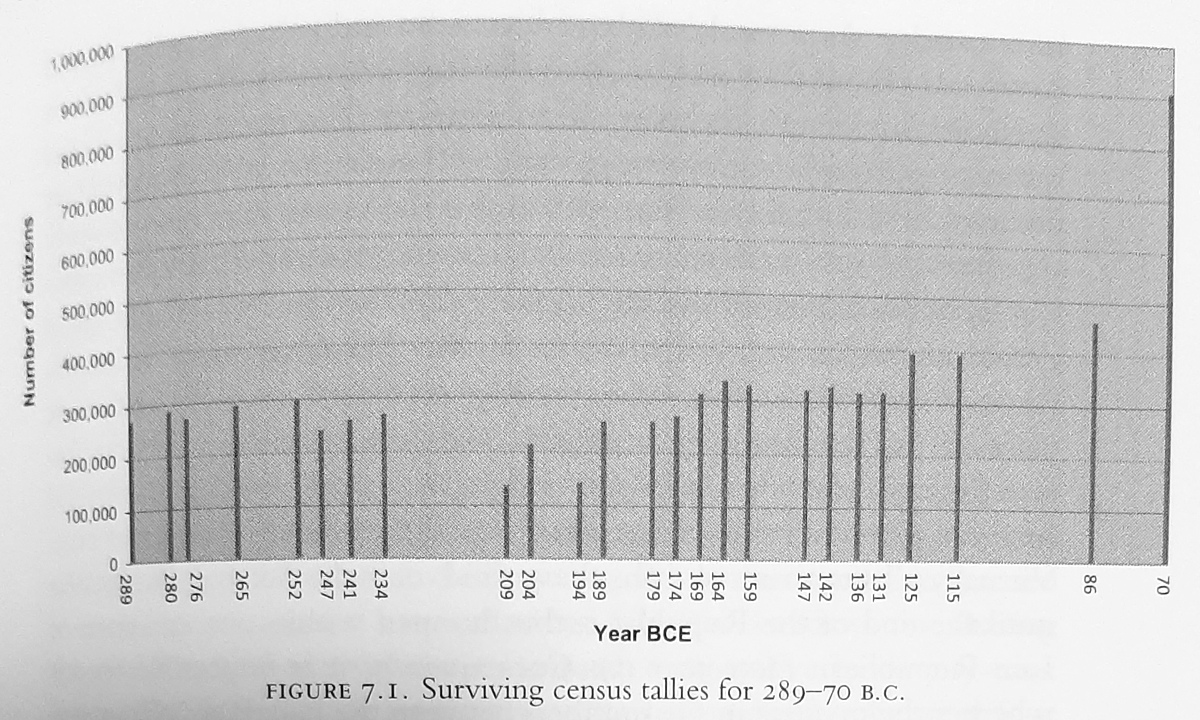

Census figures for Roman citizens in 265/4 counted 292,234 citizens,[25] of whom the property owning assidui, representing the wealthy voting blocks in the public assemblies, were also liable to pay the tributum tax that ultimately paid the soldiery’s daily stipendum.[26] Every five years citizens were required to register with the censors their positions in terms of property class, tribe and centuria, “for the purpose of taxation, mobilization, and vote.”[27]

The non-voting civitas sine suffragio comprised the population of the non-Latin territories gradually being annexed by the Romans; the Samnites, for example, defeated finally in 290, were given full citizenship (civitas optimo iure), as Romani or Quirites, only in 268.[28] All of Italy would be granted full Roman (voting) citizenship only at the end of the Social War in 87 BC.

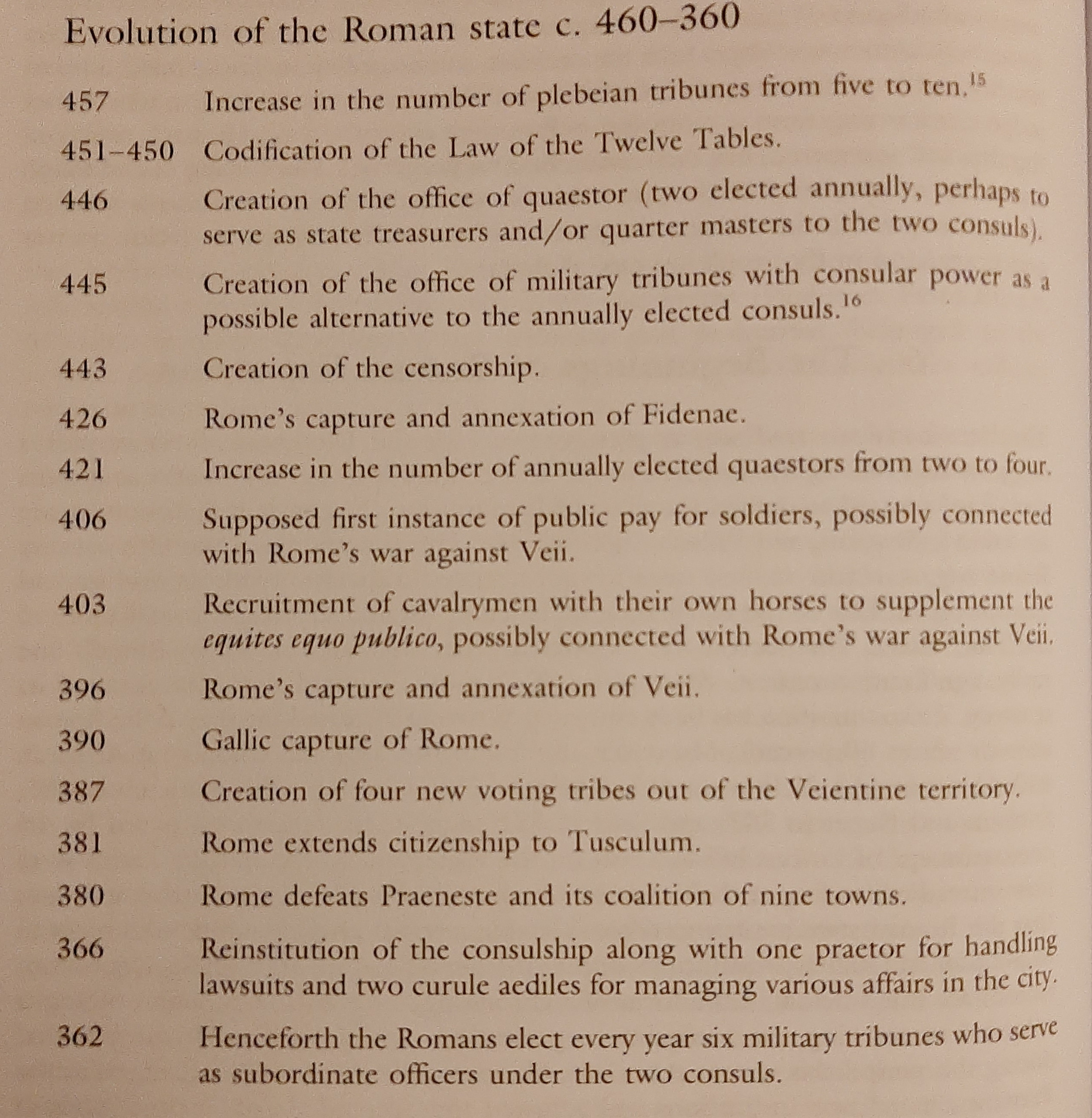

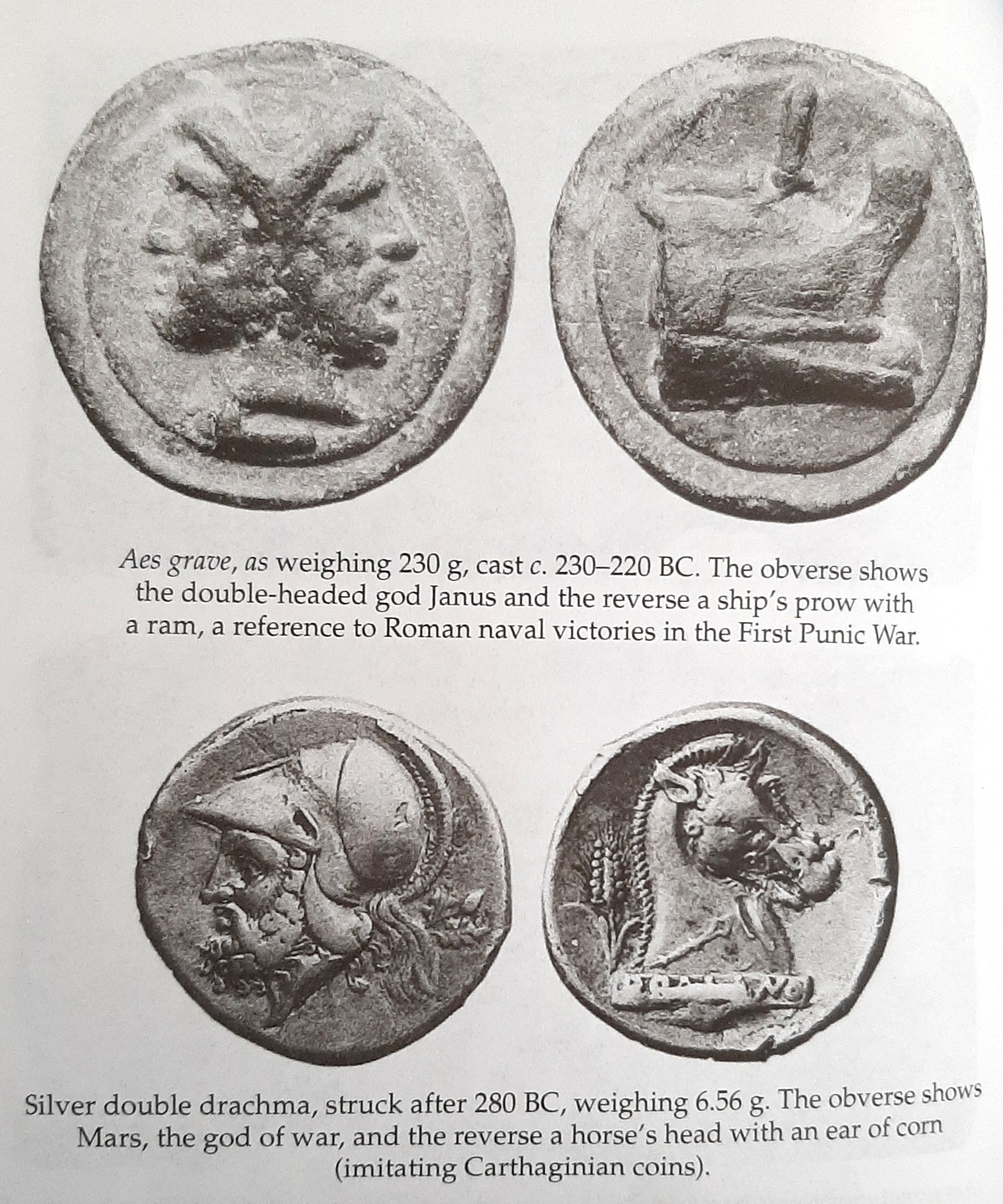

During our period of the middle republic, the Senate had increased in power against the popular assemblies as the number and importance of the Roman magistracies grew, including the introduction of the censors in 443, the creation of the first praetor in 367 and expansion of the aediles to four in 366, the year tribune Lucius Sextius was elected to the consulship as the first plebian consul.[29] The Licinio-Sextian reforms guaranteed the plebians positions in the senior magistracies,[30] and began the process by which the plebeian assembly (concilium plebis) became the comitia populi, the plebiscites of which would eventually have the power of law (leges). The Licinio-Sextian reforms included sumptuary laws which established fines for private wealth in excess of 500 iugera (about 300 acres of land or 100 cattle or 500 sheeps, pigs, etc.), indicating that there was some desire to control the growth of individual wealth.[31] In 366 Lucius Sextius himself was elected as the first plebeian consul.[32] From the Genucian laws of 342 onwards at least one of the consuls had to be a plebeian.[33] The Lex Genucia of 342 also prohibited interest charges on debt, as well as limiting magistrates to only a single office at a time, with ten years between terms in the same magistracy, beginning the arrival of the ‘new men’ in Roman politics.[34] The first plebeian dictator, Gaius Marcius Rutilus was appointed in 356,[35] and he later became the first plebeian censor in 351.[36] Quintus Publilius Philo, the lawmaker, became the first plebeian praetor in 336.[37]

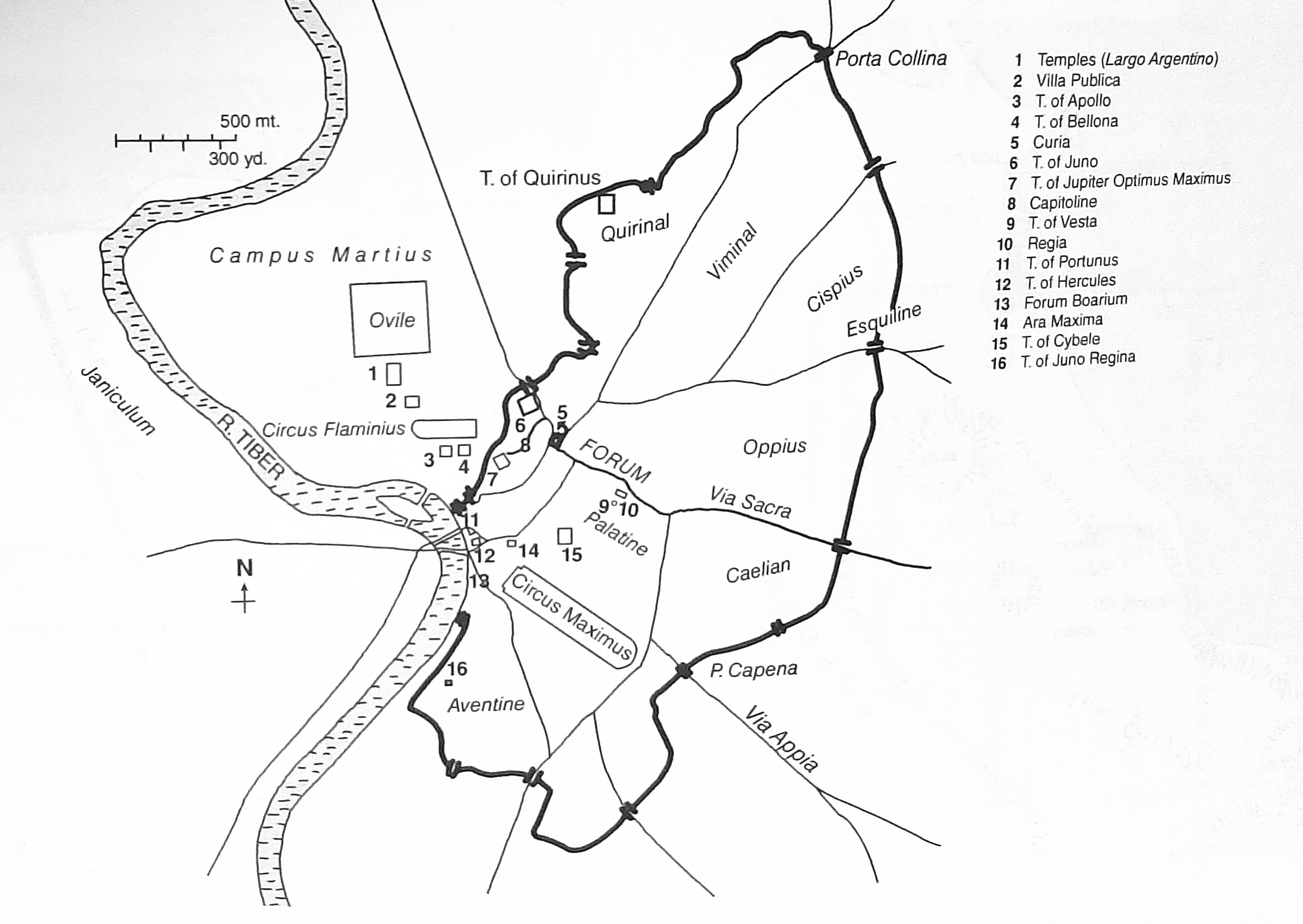

Archaic Rome in the 6th century, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008), & model of the same.

The three Lex Publilia of 339 affirmed that the decisions of the plebeian assemblies would be law, but that, significantly, the assemblies would vote only after the Senate had given its ‘authorisation of the Fathers’ (auctoritas partum).[38] Between 339-318, the Lex Ovinia gave the censors responsibility for determining the makeup of the Senate.[39] Debt-bondage and debt relief for the plebs were perpetual issues, the former institution of nexum being abolished by the Lex Poetelia in 326.[40] A law of 311 established that military tribunes were to be elected rather than appointed by the consuls.[41] The Lex Valeria of 300 reinforced the citizen’s right of appeal (ius provocationis),[42] and c. 289-286 the Lex Hortensia is generally considered to have concluded the centuries-long Conflict of the Orders by abolishing plebeian debt altogether, and re-affirming the original decision of the Lex Horatia of 449, and the Lex Publilia of 339, that the decisions of the comitia populi were legally binding, meaning they could pass their own laws independent of Senate resolutions.[43]

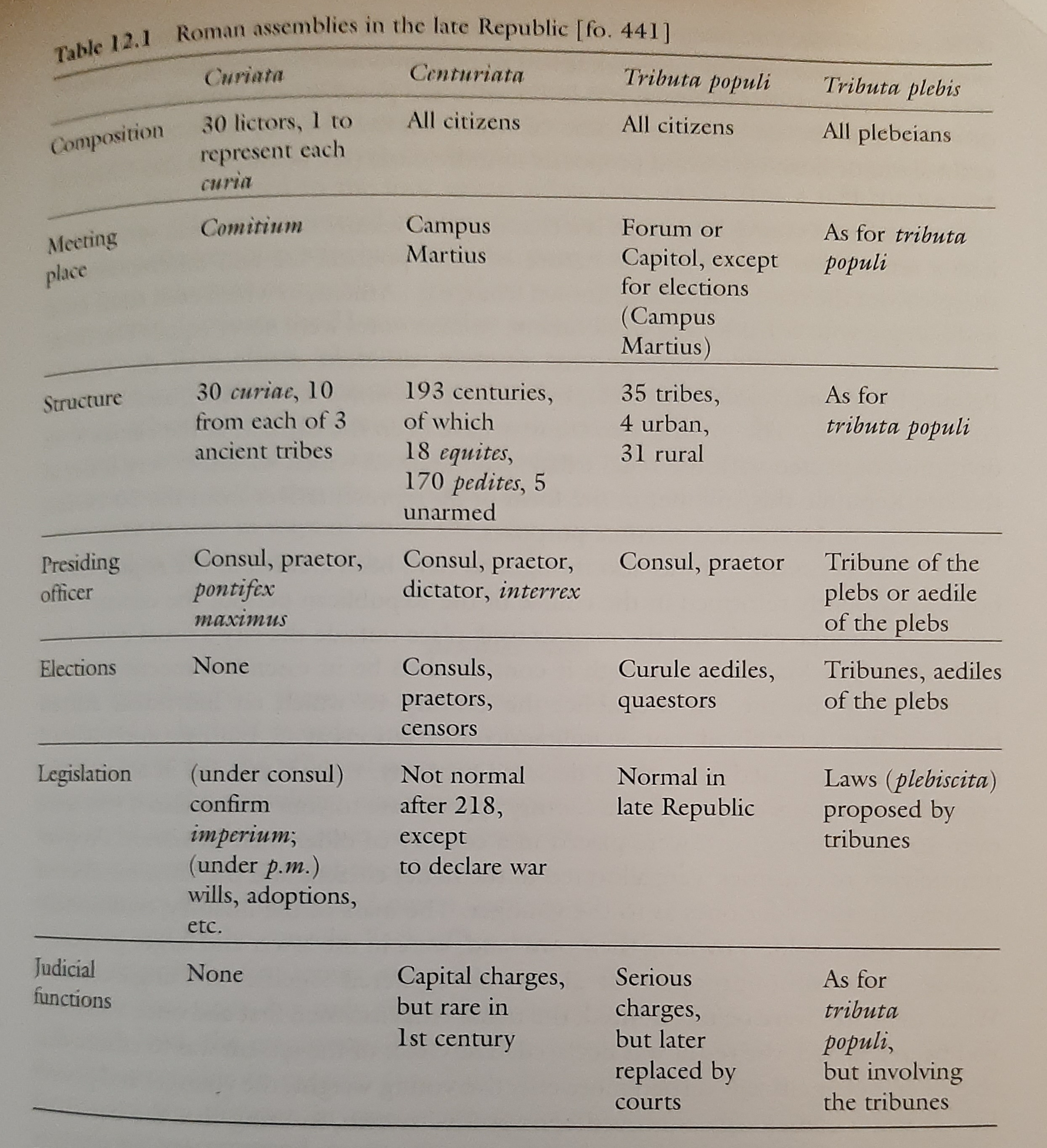

The Assemblies

The Roman state structure of the 3rd century BC was divided into several political and religious branches, but was dominated by the aristocratic land-owning Senate. The plutocratic equestrian elite, and their tribal subdivisions, governed from the Senate through the elected and former magistrates, who put questions before the assemblies and ensured (mostly) their support. The Roman assemblies were becoming increasingly concerned with parochial politics, since the Lex Publilia of 339, ratifying decisions already made in the Senate, although the comitia centuriata’s prerogative to elect consuls and decide on war made it a powerful direct decision-making apparatus, but it generally ratified whatever decisions the Senate had made, only initially disagreeing with the Senate’s auctoritas partum, in 241, 222 and 200.[44]

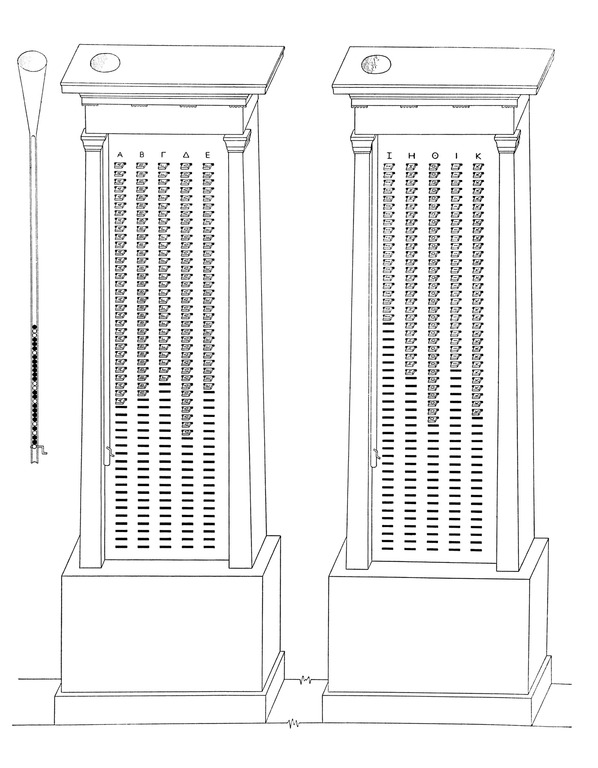

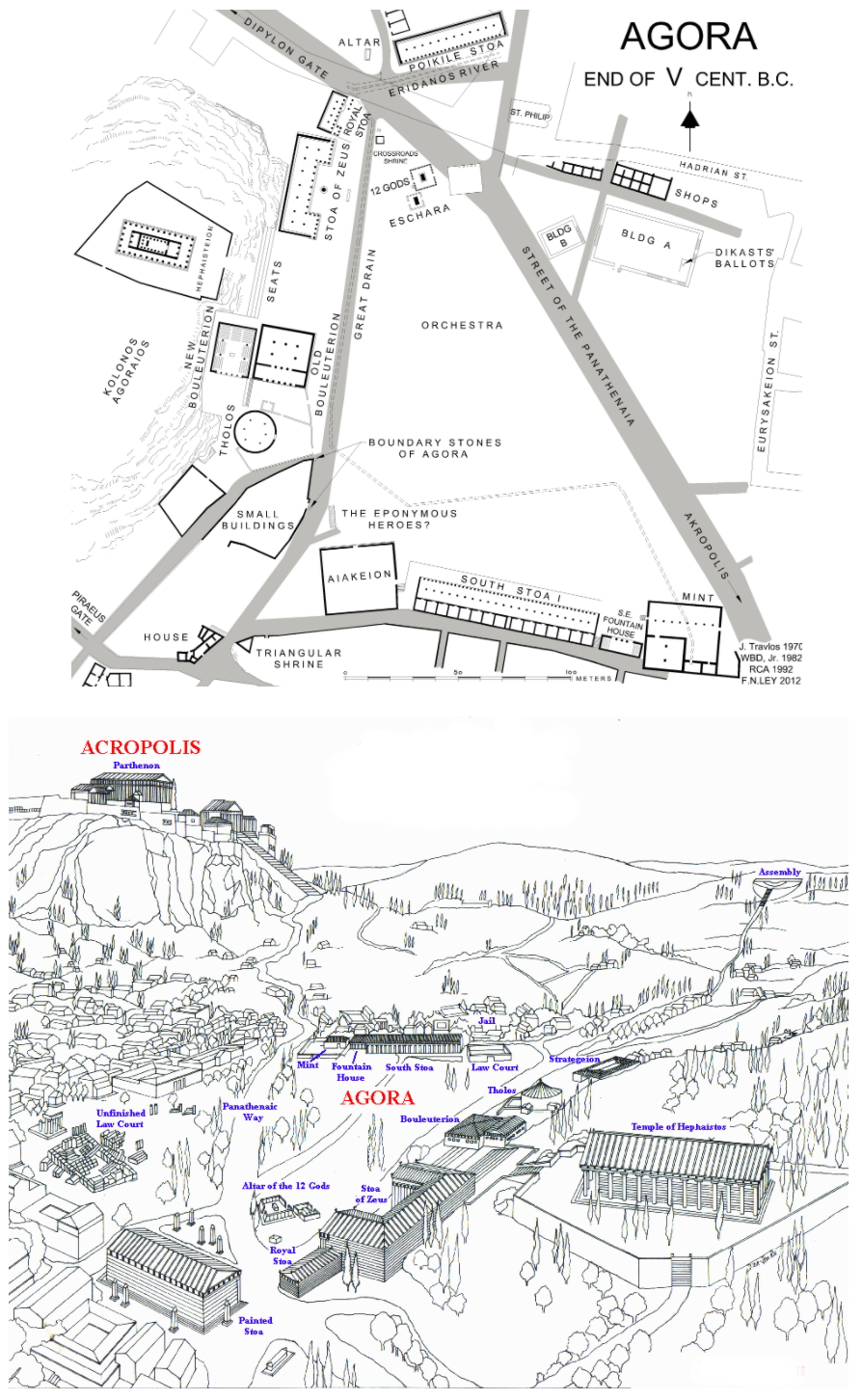

The consent of the citizens of Rome was required to ratify legislation promulgated by the Senate, which was the role of popular assemblies, similar in purpose although not in function with the Spartan apella, or Athenian akklesia.[45] In the Roman case, the system was divided into several comitia based on wealth, family, and tribe. The comitia centuriata, by virtue of representing the leadership of the Army – initially the wealthiest property owning citizens in the republic – was a military and judicial assembly, responsible for electing the consuls and praetors, and originally also the tribunes,[46] and the conduct of trials in capital cases.[47]

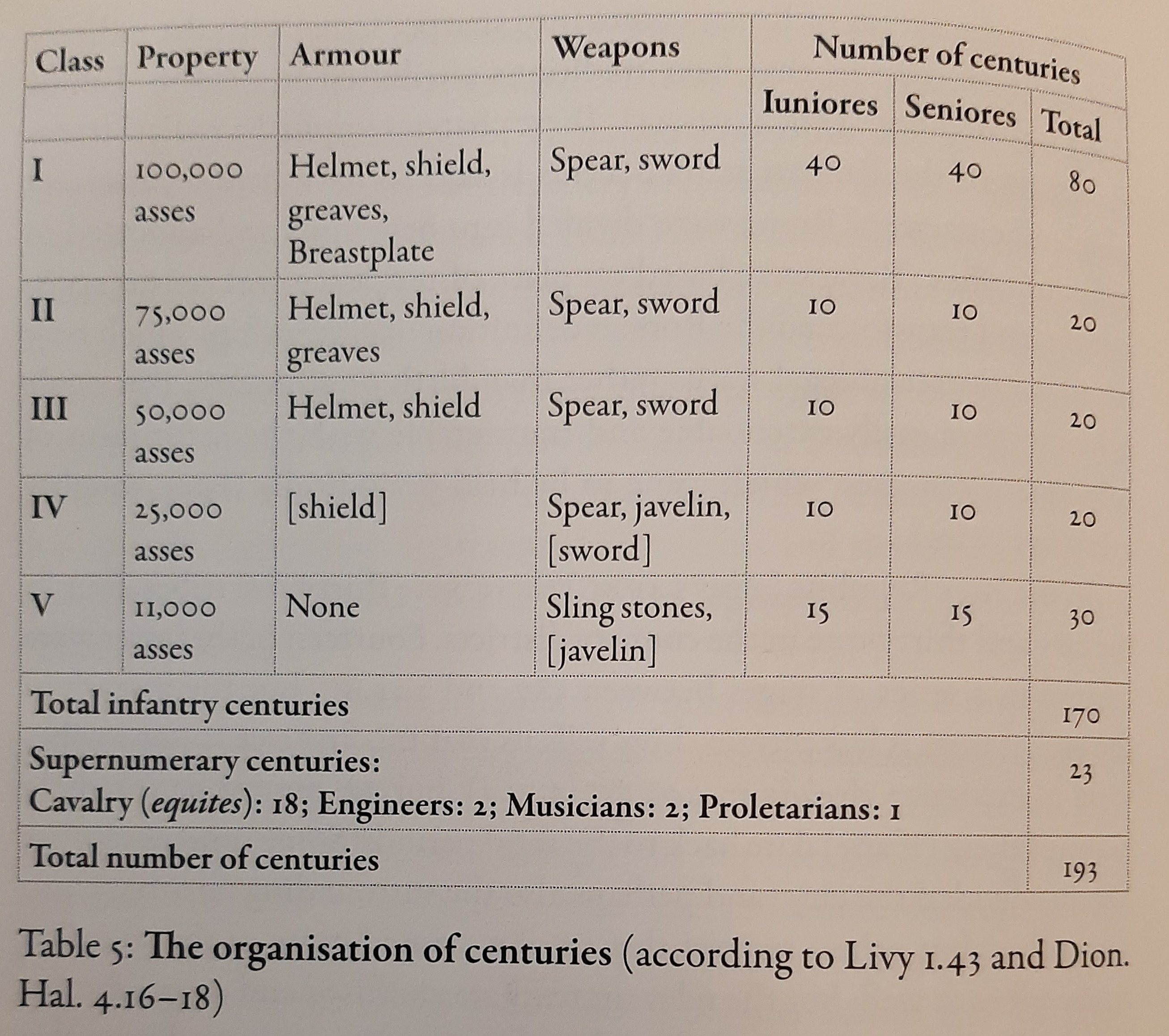

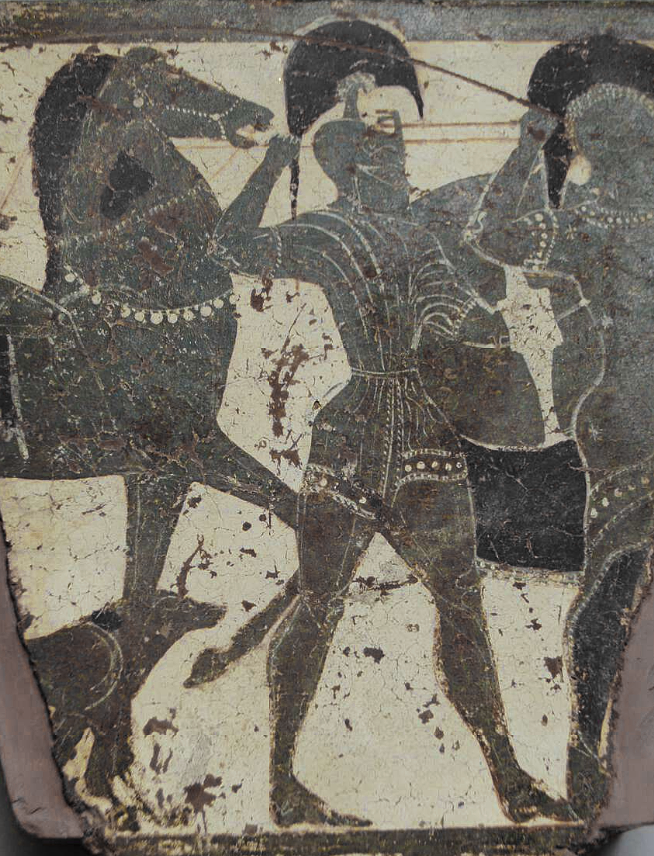

The sixth Roman king, rex Servius Tullius had established (c. 550) 193 centuries, representing the various classes of wealth in ancient Rome. The first class were given the majority of 100 by design: 18 elite cavalry centuries plus 82 infantry (pedites) centuries (40 senior and 40 junior, and two engineering centuries), representing the richest citizens, with their property valued as at least 100,000 asses. They were armed in the tradition of the bronze armoured hoplite, and had originally emerged in the archaic period between the late 7th century when the Forum was filled in, and the mid-6th century when hoplite warfare had proliferated in Greece.[48] The second class of 20 centuries, again divided into ten senior and ten junior for civil defence and field operations, wore less complete armour than the first class, and required at least 75,000 asses to qualify. 50,000 asses was enough to qualify for the 20 centuries of the third class, as was 25,000 for the 20 centuries of the fourth class – by which point these infantry were unarmoured, carrying only javelins and spears. The fifth class comprised 30 centuries of slingers and two centuries of drummers and buglers, with assets at 11,000 and 12,500 asses (this draft cut-off would be lowered to 4,000 asses as an exigency of the Hannibalic War in 211).[49] A single sixth century, the proletarii,[50] including everyone not totally impoverished, was only used in rare circumstances to break ties, although it did ensure that the proletarri at least could be present at centuriata meetings.[51]

Roman census, 508-234 from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008)

3rd century Roman citizen census figures from Gary Forsythe in A Companion to the Roman Army, ed. Paul Erdkamp (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011)

Census figures, 289-70 BC, from The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic, ed., Harriet Flower (2014)

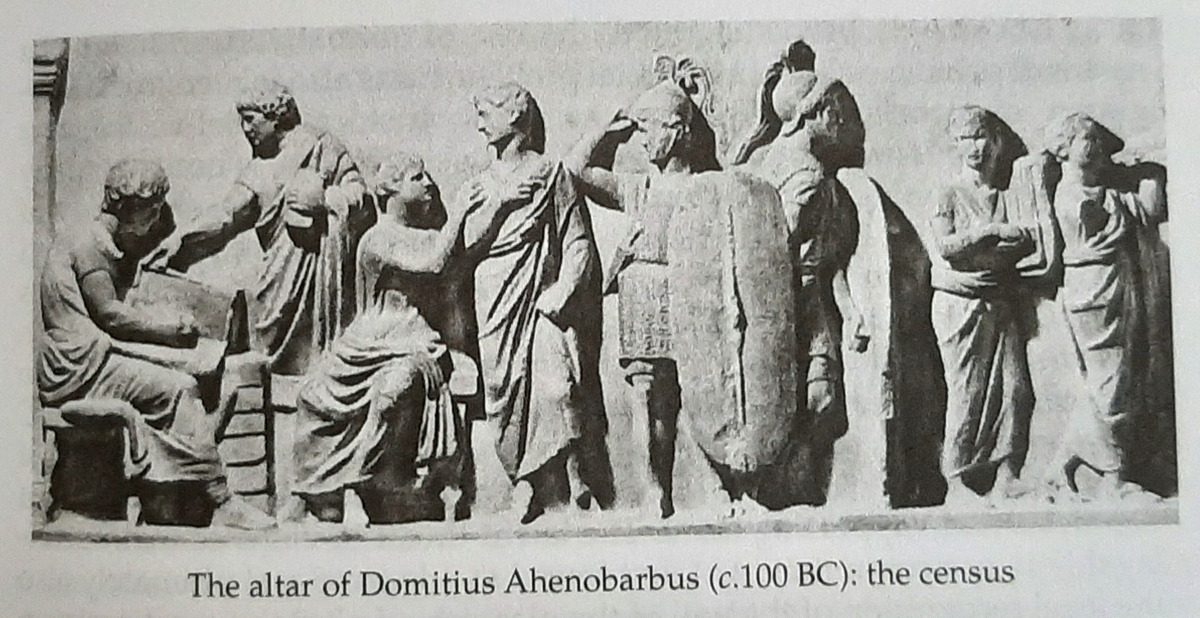

Census underway, from Klaus Bringmann, A History of the Roman Republic (2007)

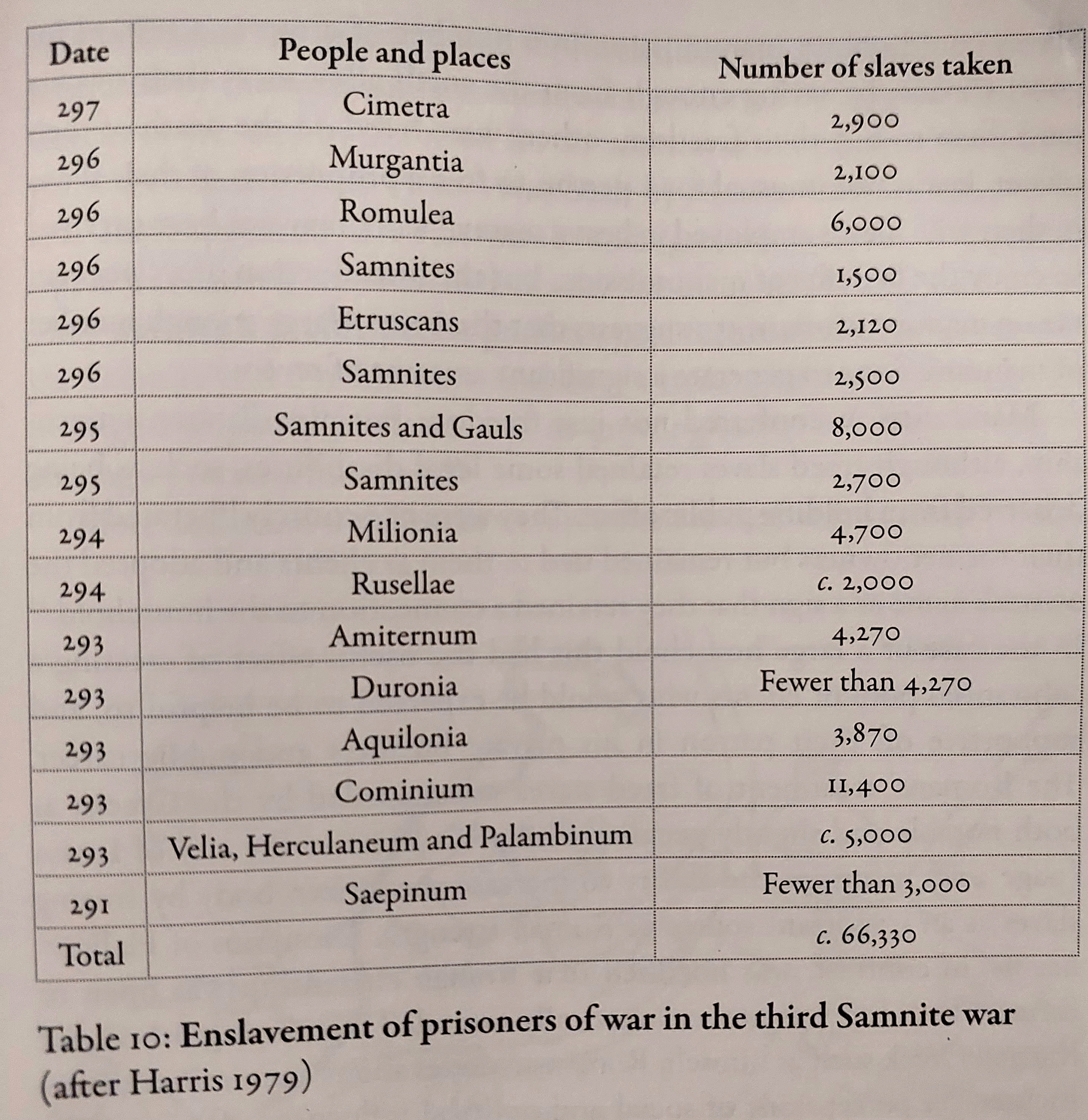

Discounted were the property-less, the capite censi, and of course women and slaves, the latter of the latter of whom there were a great many – 66,330 people had been taken as slaves during the six years of the Third Samnite War, 297-291.[52] Decisions were usually reached by the first four centuries, if not the first outright.[53] Mouritsen portrays a highly managed assembly process, wherein the first block of voters were chosen by lot as one of the 80 first class centuries to become the centuria praerogativa, whose vote would then essentially determine the outcome of the measure at hand (ie, voting in the centuriata was a ratification process).[54]

Slaves taken in the Third Samnite War (297-291), from Kathryn Lomas, The Rise of Rome (2018)

The Army (of which more below) could not enter the city, as the imperium power did not exist within the sacred pomerium boundary of Rome, representing the distinction between the domi, Rome as a domestic city, and the militiae, the field in which the Roman army operated.[55] The comitia centuriata, representing the Republican Army marshalling, therefore, met outside the city on the Field of Mars (Campus Martius).

Evolution of Roman State, from Gary Forsythe in A Companion to the Roman Army, ed. Paul Erdkamp (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011)

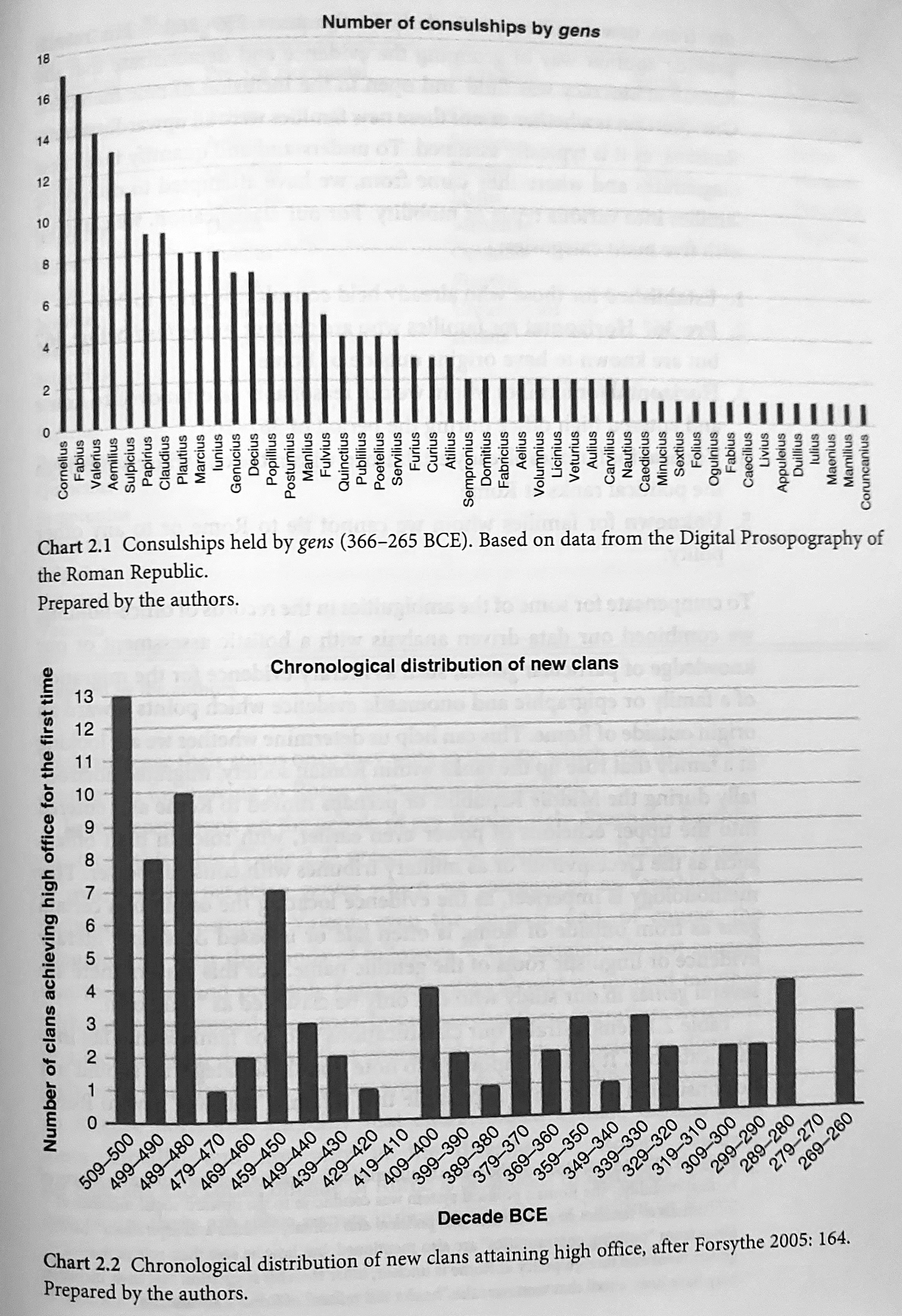

Clans holding consulships, 366-265, from Parrish Wright and Nicola Terrenato, ‘Italian Descent in Middle Republican Roman Magistrates’ in Making the Middle Republic, ed., Seth Bernard, Lisa Marie Mignone, and Dan-el Padilla Peralta (2023)

Traditional military classes of the comitia centuriata, from Kathryn Lomas, The Rise of Rome (Harvard University Press, 2018)

The familial, or regional, assembly was the comitia curiata, which was presided over by a consul or praetor and was responsible for granting ‘military auspices’ to those magistrates elected by the comitia centuriata. The 30 curiae originally represented the archaic military organization (3,000 infantry, 300 cavalry) of the proto-Roman army, after the Servian reforms had become a largely ceremonial body as power was transferred to the property holders outside of Rome in both the comitia tributa and comitia centuriata.[56] The comitia curiata assembly represented the 30 city ‘wards’ but became increasingly circumvented as the republic progressed until it was purely a pro forma institution during the 1st century.[57]

In 471 the plebs had managed to wrest control of the election of tribunes from the comitia centuriata, with that important magistracy passing first to the tribal committee, comitia tributa, and later to the concilium plebis (including responsibility for the election of plebeian aediles).[58] The comitia tributa,[59] which again favoured the landowners as it was divided into only four ‘urban’ and the remainder ‘rustic’ tribes, with the number of the latter landowning tribes growing by two in 358, 332, 318, 299, 241, until there were 35.[60] However, as majority of 17 tribes was required for a decision, the comitia tributa was not necessarily always weighted in favour of the landowning elite. This had especially been the case under the democratizing reforms of Appius Claudius Caecus in 312, who intended to distribute the lower classes (humiles) more broadly across the tribes.[61] The comitia tributa was responsible for electing the quaestors and aediles, and was responsible for public cases that involved fines.[62]

As Polybius famously explained, by the time of the Punic Wars the political power in Rome was divided between the powers of the former kingship, the aristocracy, and the people’s assemblies.[63] The old patrician clans still exerted their power (Valerii, Claudii, Fabii, Aemilii, Cornelii, Manlii, Fulvii, Mamilii, Otacilii, Stilii, Genucii, Licinii and the Plautii),[64] but increasingly ‘new men’ were present in the senior magistracies, with their own route to power through the tribunate.

Pre-Roman Italy, from The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic, ed., Harriet Flower (2014)

Tribes of Italy, c. 3rd century, from Kathryn Lomas, The Rise of Rome (2018)

The Senate

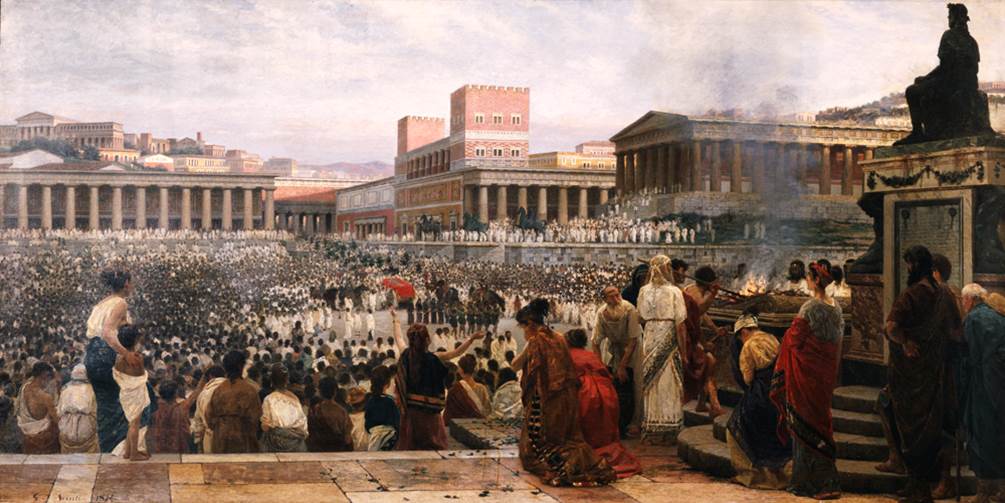

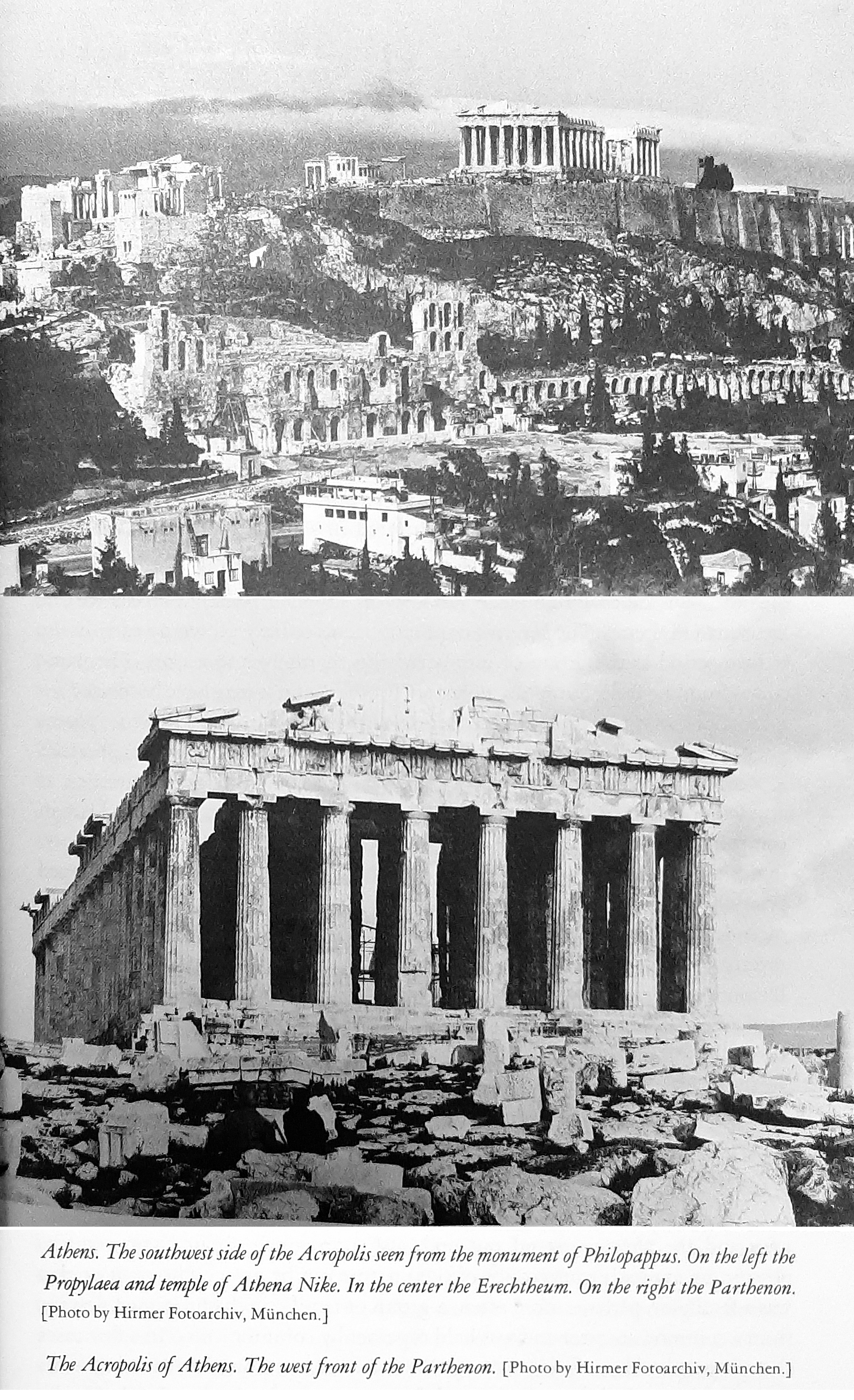

Meeting athwart the Comitium in the Curia Hostilia, the 300 senators of the Roman Senate were responsible for conducting diplomatic affairs, managing state finance, and administrating the city’s bureaucratic and religious institutions. The Senate gradually expanded in plurality, creating what became known as the ‘race of honour’ cursus honorum of ambitious and wealthy citizens, effectively the civil bureaucracy that governed Rome and fought its wars. Magistracies had been monopolized by the patrician senators since the demise of the monarchy. Indeed, the Senate had originally acted in the capacity as a council for the king,[65] and in this regard was similar to the Spartan royal council, the gerousia of 30 (including the two kings),[66] or the Aeropagus council of former living Athenian archons, who controlled important government functions and influenced politics and strategy.[67] Speaking order in the Senate began with the elected consuls, and then passed next to the former consuls, of whom the most senior was the princeps senatus, and then on to the lesser magistrates.[68] Fundamentally, career magistrates would possess both considerable military and administrative experience, and have accumulated aristocratic and public honours (honores) through their martial courage (virtus), renown (gloria), reputation (fama), familial legacy and commanding dignity and authority (auctoritas).[69] During Rome’s long wars for control of Italy, the magistracy gradually became accessible to the property owning plebeians as their wealth and influence increased relative to the patrician establishment.

Structure of the Roman republican government

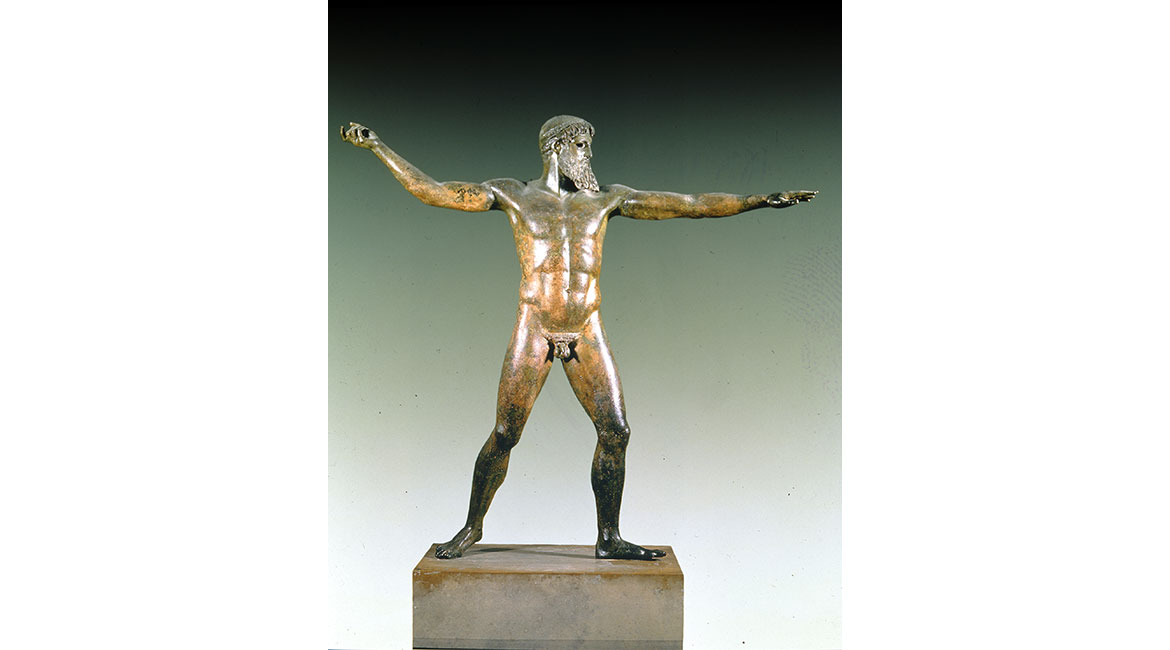

The executive or old monarchical power (imperium) and its corresponding religious power (maxima auspicia),[70] was held by the two annually elected consuls, both of whom commanded Rome’s armies, presided over the popular assemblies, and acted as leaders in the Senate. During emergencies the Senate could also temporarily appoint a dictator for the duration of six months, overriding all other legal constraints.[71] Dictators were supported by a magister equitum, master of the horse, responsible for marshaling the equites, that is the, the propertied cavalry class and by extension acting as a whip in the Senate.[72]

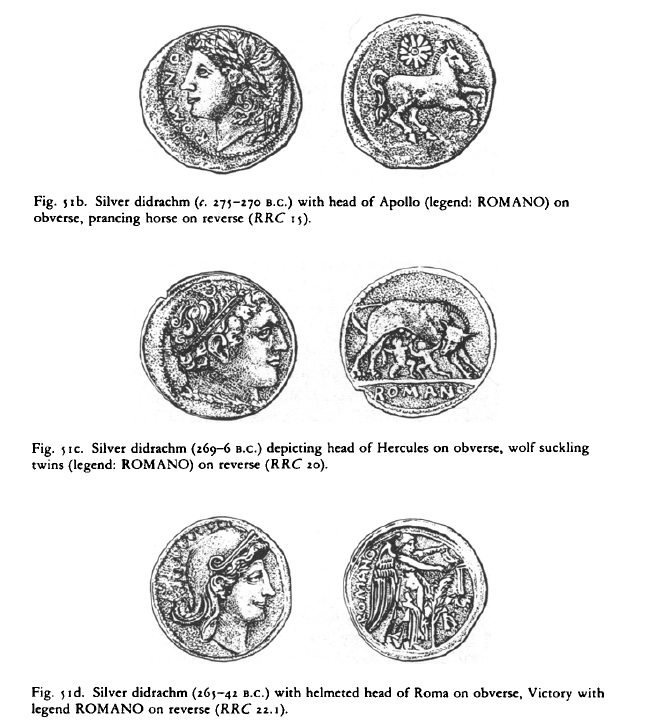

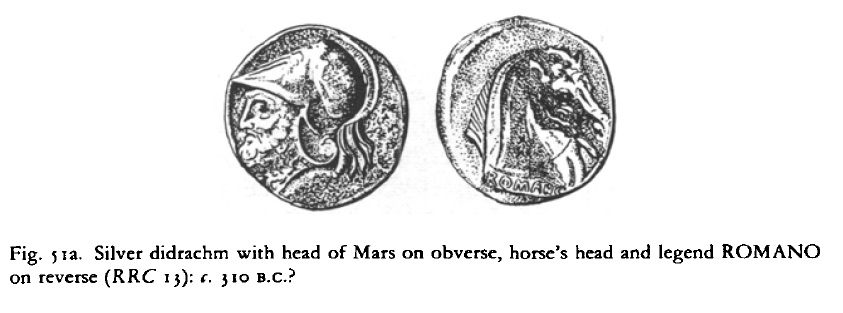

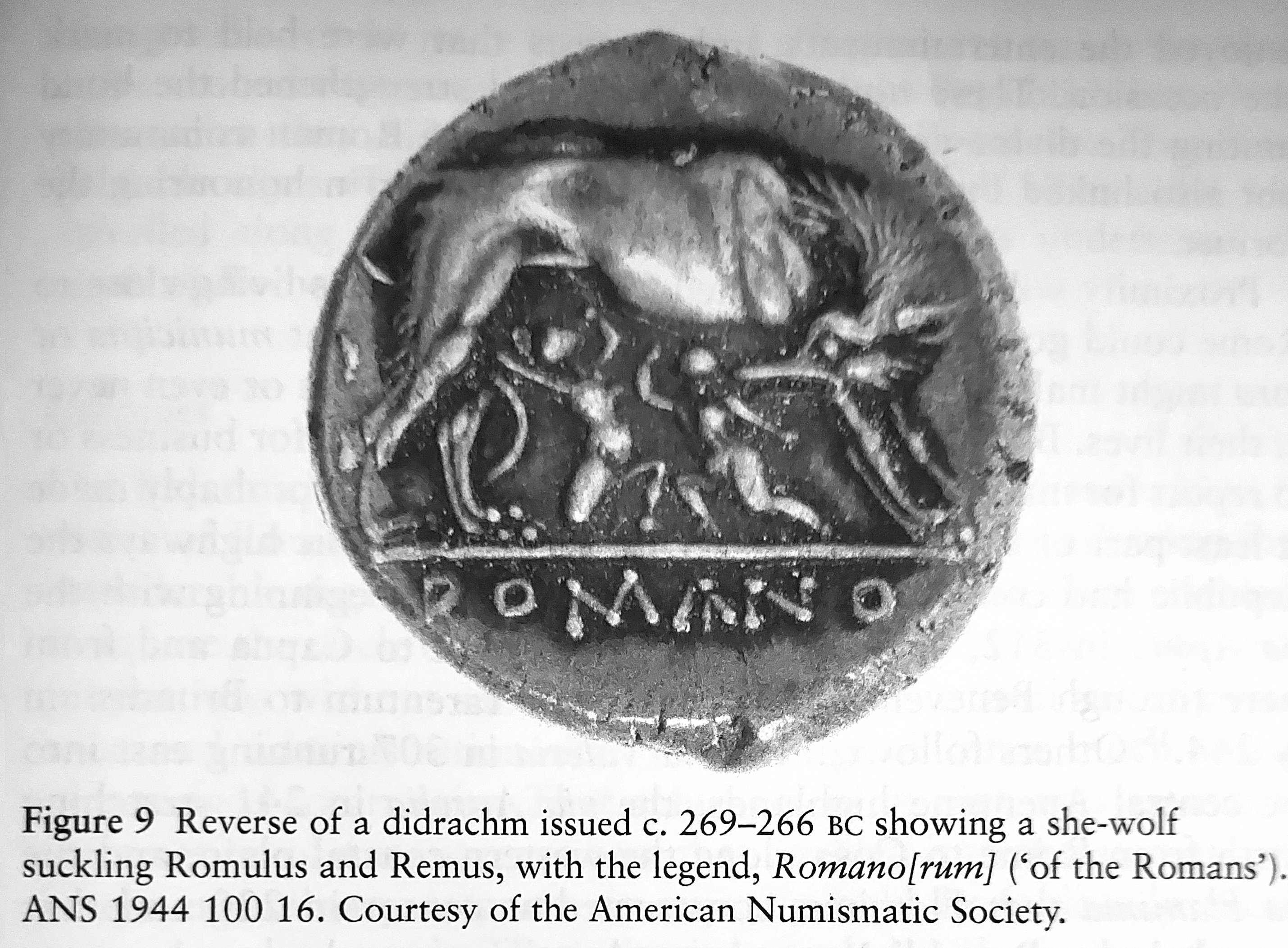

The consuls’ power to levy funds remained with the Senate in peacetime, and they did in fact rely on the Senate, whose membership included the elected and former quaestors, legal and financial functionaries responsible for lawsuits, government contracts, and the logistical measures,[73] necessary to provide material, funds and supplies for campaigns.[74] Polybius noted that the consuls could draw money directly through the quaestors on campaign. Indeed, the origin of Roman coinage relates to the need to pay troop levies: Bronze Roman bars as currency were introduced under the authority of the newly created triumviri monetales in 289, Roman didrachms were being issued by 281, and the first Roman mint was opened in 269 to produce silver didrachms.[75] One of the eight quaestors was usually attached to handle each consuls’ finances, while two quaestors stayed at Rome to manage the city’s treasury (aerarium).[76] These financial and bureaucratic mechanisms were smoothed by the attendance of a variety of secretaries known as apparitors,[77] lesser bureaucrats such as legates who initially acted as messengers beyond the city’s boundaries,[78] and other staff such as the slave nomenclators who were responsible for memorizing the names of important people the senior magistrate interacted with on a regular basis.[79]

Roman republican coin, c. 280-230 BC

Roman silver didrachm, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008)

Aes grave, as with Janus plus First Punic War ram, silver double drachma (didrachm), from Klaus Bringmann, A History of the Roman Republic (2007)

‘Romano’ silver didrachm c. 269-266, with she-wolf and twins, from Rosenstein, Rome and the Mediterranean (2012)

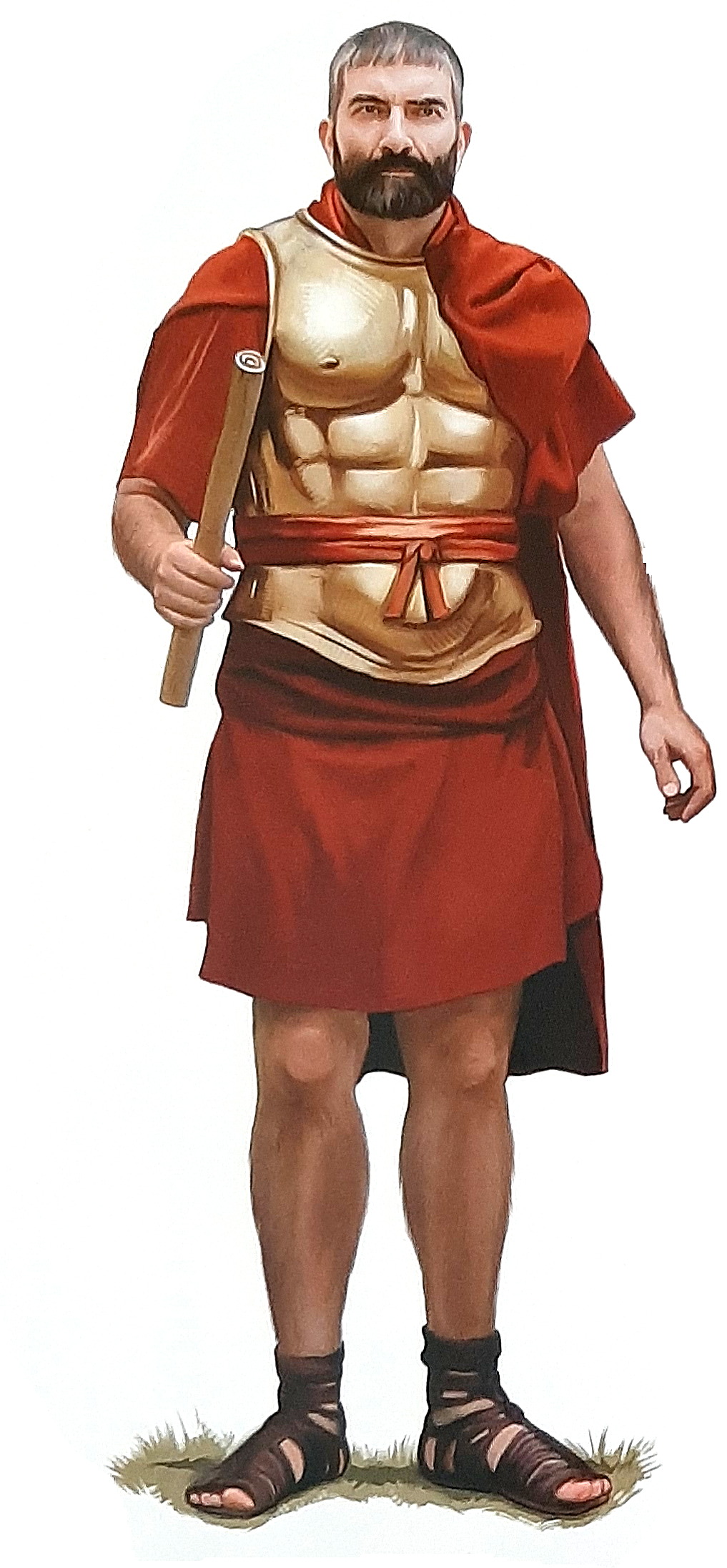

The consuls could potentially face prosecution by the magistrates in the form of an audit, similar to the Athenian euthyna, although without the prospect of ostracism, carried out at the end of a consuls’ term(s) and meant to expose signs of financial malfeasance.[80] After the institution of the Genucian laws in 342 the consuls could only be re-elected after a decade had elapsed between terms, although this rule was often violated during military emergencies.[81] The consulship was held on several occasions by experienced proconsuls, but this reflects wartime extremities – between 289 to 255, out of 70 consulships a total of 65 were held by different people.[82] In 327 it became possible for the popular assemblies to extend the consuls’ terms by prorogation, in which case the consuls became pro consule, and praetors the pro praetore; a useful instrument when the magistrate was away governing a province or colony, or on an extended campaign.[83] On campaign the consuls wore Etruscan crowns and robes and were attended, when exercising their power, by twelve lictors who carried the fasces, an axe wrapped in rods.[84] The appointing of military tribunes for lower army command rested initially with the consuls, although these commissions were ratified at the outset of the campaign in the comitia centuriata. The consuls also had a number of diplomatic and religious duties to administer before departing for their theatre of operations.[85]

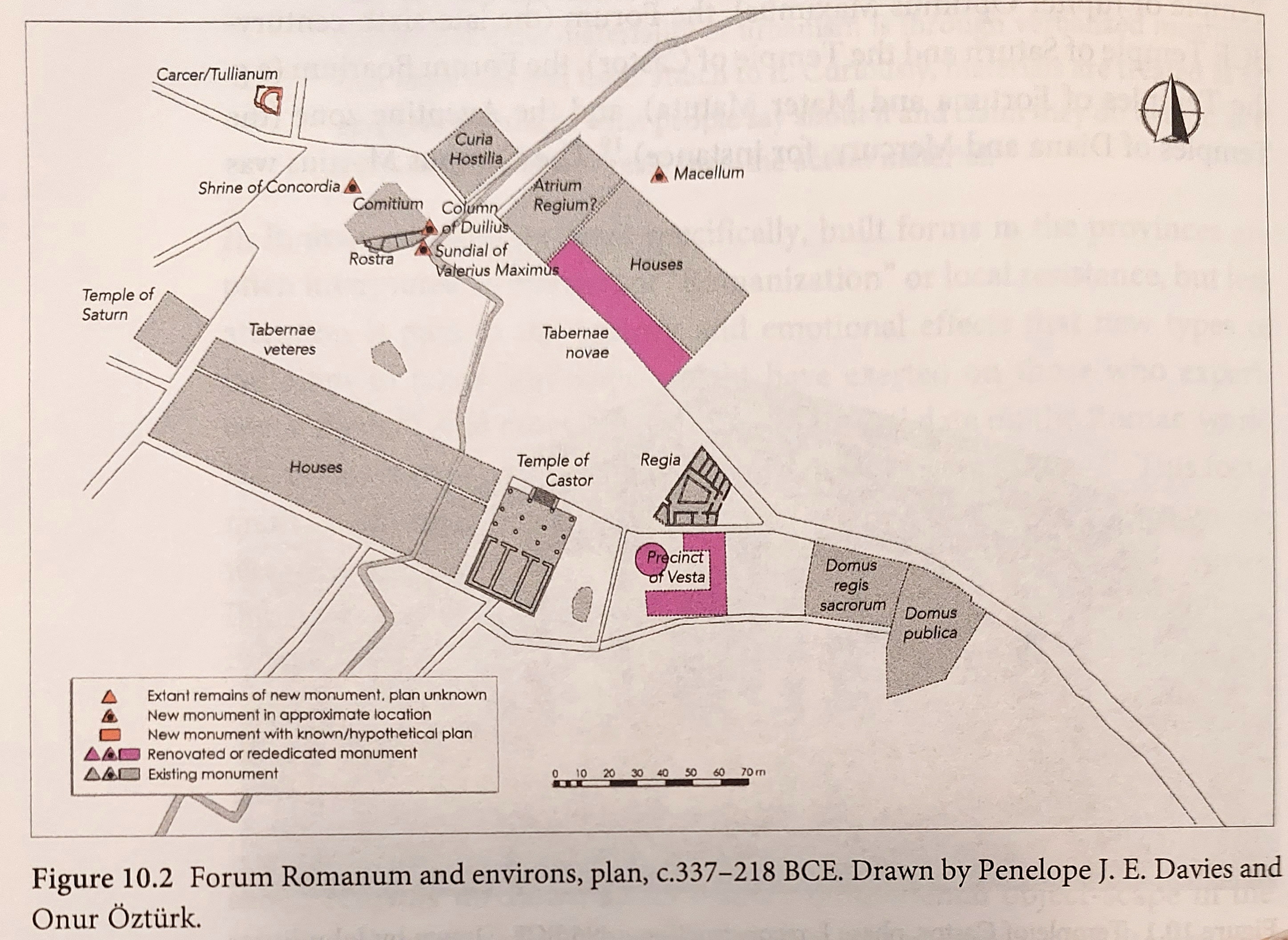

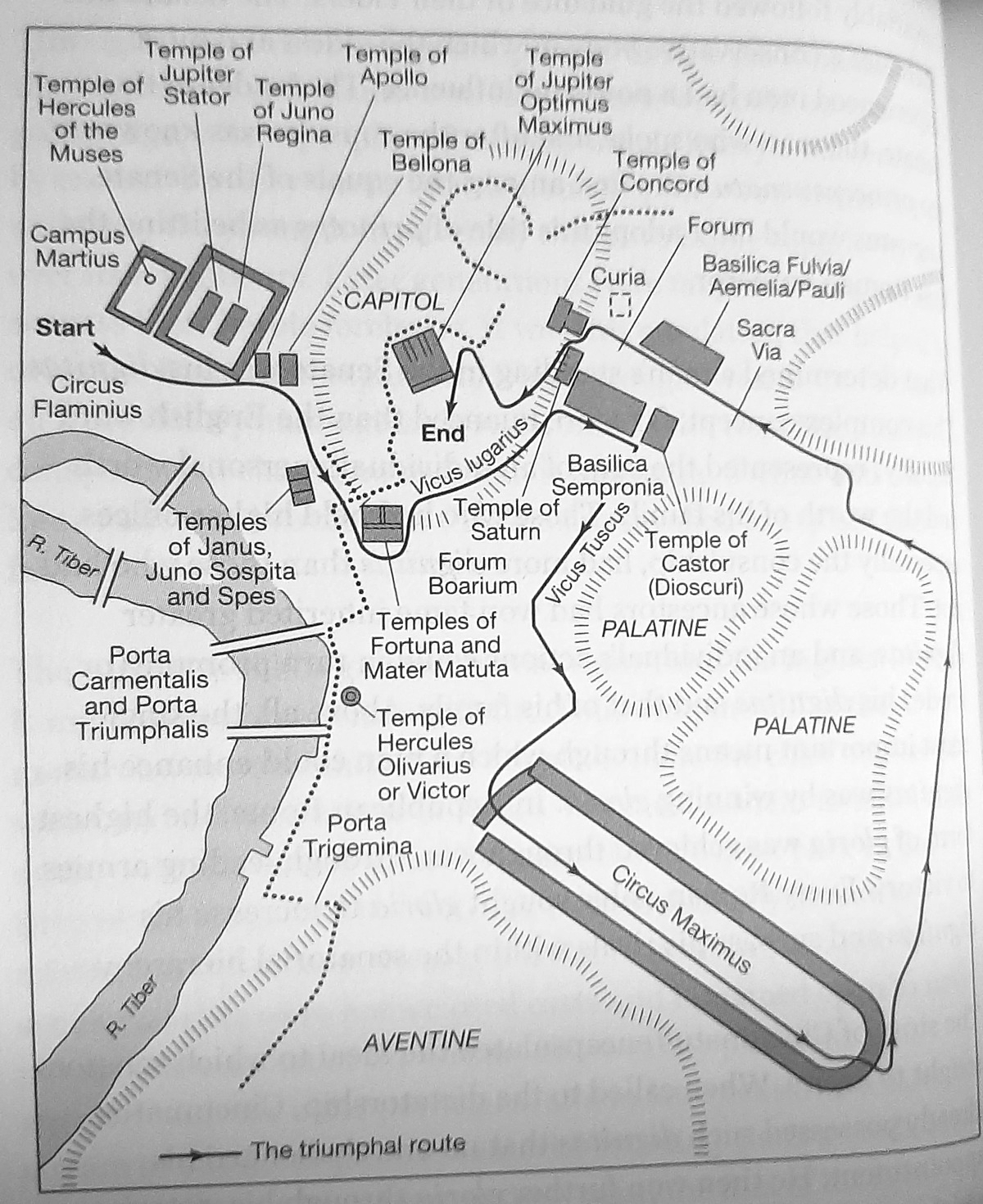

Map of the forum, from Penelope Davies, ‘Architecture’s Agency in Fourth-Century Rome’ in Making the Middle Republic, ed., Seth Bernard, Lisa Marie Mignone, and Dan-el Padilla Peralta (2023)

The Roman Magistracy

For the elite of the patricians and plebeians families alike, holding magistracies, elected public offices, and positions in the Senate, was the goal of one’s public and political career. During the Middle Republic, citizens at least 27 years old (ie, who had completed 10 years of military service) could be elected quaestors, 33 years was the minimum age for praetors, and 36 years the minimum for consuls.[86] The most senior position in the magistracy was that of the two censors, who were responsible for enforcing morality, issuing contracts to the citizenry for construction and repair of public works and all public land holdings (such as harbour, orchards, mines, rivers, farms, etc),[87] and revising the Senatorial property list (lectio senatus) – necessary to vote in the comitia centuriata.[88] These powerful purple-robed officials were usually former consuls and were elected for a period of 18 months every five years.[89]

Functions of the Roman magistrates, from John North in A Companion to the Roman Republic, ed. Nathan Rosenstein & Robert Morstein-Marx (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2007)

At the opposite end of the seniority spectrum were the four aediles, two patrician curule aediles and two plebeian aediles,[90] who were collectively responsible for the urban concerns of Rome: supplies of grain and water, maintenance of roads and markets, preventing fires, holding games;[91] the quaestors (financial administrators), and the ten plebeian tribunes. When the army was assembled a number of military tribunes (tribuni militum) were elected by the centuriata, no doubt with the input of the presiding consuls, who then acted in the function of leadership for the legions, six military tribunes per legions (see Army organization below).

The aspiring magistrate would move up the ladder first as a plebeian tribune or patrician quaestor, then aedile or praetor, before seeking election as a consul or censor by the age of 40.[92] All magistrates (although not the tribunes, until the time of the Gracchi) held seats in the Senate, which was the true legislative, financial, and in certain cases legal, power-centre of the Republic, as all legislation at some point passed through the Senate regardless of its origins (although its consent was not always required),[93] and the Senate was otherwise in general control of the state treasury,[94] foreign relations, and was responsible for trying high crimes such as treason.[95] The usual Roman legislative process since the Lex Publilia of 339 was for the Senate to discuss legislation, or meet with ambassadors and dignitaries, before passing on their recommendations to the comitia, either centuriata or tributa for voting and ratification.

Bills originating from tribunes who had convened the concilium plebis, after the Lex Hortensia of c. 289-286, would likewise be seen by the Senate and then voted upon by the comitia in the usual way.[96] It was also possible to convene purely discursive meetings with no decision-making powers, known as contiones, again demonstrating the interplay between Senate, magistrates and the Roman citizenry (Quirites).[97] Whatever resolution the magistrates and the Senate took, implementation required the consent of the citizens and the gods, and lavish rewards were promised to both.

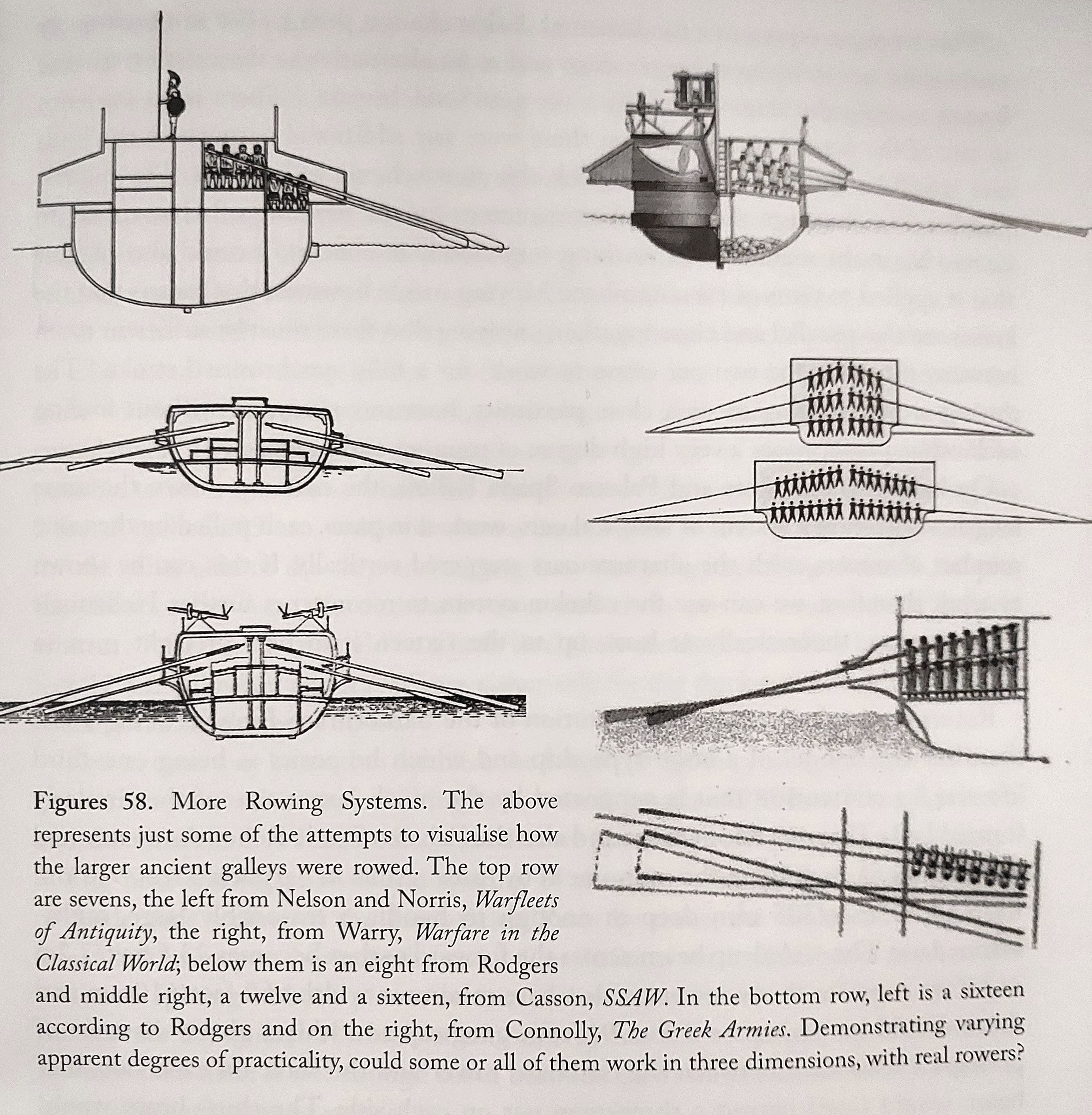

Rome in the Age of the Italian Wars (4th century BC), from Livy, Rome’s Italian Wars (2013) & early 3rd century, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008)

The power of the people was represented first by the elected tribunes, originally five civil (tribuni plebis) and five military (tribuni militum).[98] The tribunate had emerged as a result of the class struggle between the office-holding patrician clan–elite and the mass of the population who composed the army, the plebeians, during the 5th century. In 494 the patricians, as a result of the First Secession of the Plebs during the debt-induced Conflict of the Orders, were forced to provide the plebs with recognition in the form of their own comitia, the concilium plebis,[99] and its initial popularly elected tribunate of five,[100] as was arranged by the respected former consul Menenius Agrippa in 494/3.[101]

These new plebeian magistrates would act in a function similar to that of the five Spartan ephors who comprised their Ephorate, which, as Aristotle observed of that Laconian legislative institution, ensured that, “the people at large can share in the enjoyment of this highest of offices, and the popular will is therefore enlisted in support of the constitution.”[102] No member of the Senatorial class could hold office as a tribune.[103] The consuls, with the exception of the dictator, had no legal or religious authority over the sacrosanct tribunes,[104] and Roman citizens within the pomerium (plus one mile beyond) had the right to appeal, provocatio ad populum, against consular or other magisterial actions to the popular assemblies (laws of 509, 449, and 300), through the assistance of the tribunes (ius auxilii).[105] The tribunes also possessed intercessio, the power to veto any state action, including legislation and elections, although they did not have seats in the Senate for another century.[106]

To provide the plebs with a clearly articulated legal constitution, the Twelve Tables of Roman law had been established by the first decemvirate, c. 450,[107] based on the examination of laws derived from Greece, in particular the laws of Solon and Cleisthenes of Athens.[108] In 434 dictator Mamercus Aemilius introduced a law to restrict the censors to a term of only 18 months every five years, but like much Roman law it would be forgotten or ignored until the 3rd century.

3rd century military tribune, from Kevin F. Kiley, The Uniforms of the Roman World (Anness Publishing Ltd 2019)

In 367/6 the consulate, which had between 444 and 367 been entirely replaced by military tribunates, was re-established and opened to plebeians, with the additional magistracy of the praetor created.[109] One praetor, a patrician, was elected as the chief justice of Rome itself.[110] The praetor’s power made him essentially a vice-consul, and he exercised the same military and religious authority, which meant that he could summon comitia when the consuls were away on campaign.[111] At the outset of the First Punic War there was only a single praetor (as only one was ever necessary to summon the assembles), but a second was added in 247 (inter peregrinos – ‘over foreigners’ – to differentiate from the urban praetor),[112] and two more were added in 228 to administer Sardinia and Sicily, the number of praetors reaching six by 197 as they became essentially governors of the Roman empire, indicative of the rapid expansion of Rome’s provincial administration following the outcome of the Punic Wars.[113]

At the end of the 4th century the honour of dedicating temples was transferred from the consuls to the usual Roman legislative process, and in 300 tribune Quintus Gallus passed a law opening pontifical positions to the plebeians: the first pleb pontifex maximus was elected in 254.[114] Plebeian dictator Quintus Hortensius in 287 passed a law affirming that bills from the tribunate, which had previously been known not as laws but as plebiscites (ie, a decree passed by the concilium plebis), would henceforth became law on both plebeians and patricians, with or without Senatorial approval.[115] The degree to which this was a purely democratic or autocratic ratification process remains debated, however, it did increase the power of the tribunate and the concilium plebis as legislative instruments, but the Senate retained its power to formulate and ratify legislation through the consulate.[116]

Roman Religion

Religious power was orchestrated by several colleges of priests, of which the most influential were the eight pontiffs, the pontifices, led by the pontifex maximus. By the 3rd century this was an elected official, who had supplanted the rex sacrorum (or rex sacrificolus), who had previously represented the symbolic religious power of the old kings.[117] The pontifex maximus was also responsible for the flamines (three major and twelve lesser), the haruspices (diviners), the Vestal Virgins, and a scribal bureaucracy.[118] The pontiffs were responsible for overseeing the correct application of religious law, as related to sacra or sacred events such as festivals, games, vows, sacrifices, burials, and inheritance. Amongst their many important duties, the pontifices were responsible for regularizing the variable Roman calendar, overseen on a monthly basis by the rex sacrorum,[119] and for preparing the comitia centuriata for voting.[120]

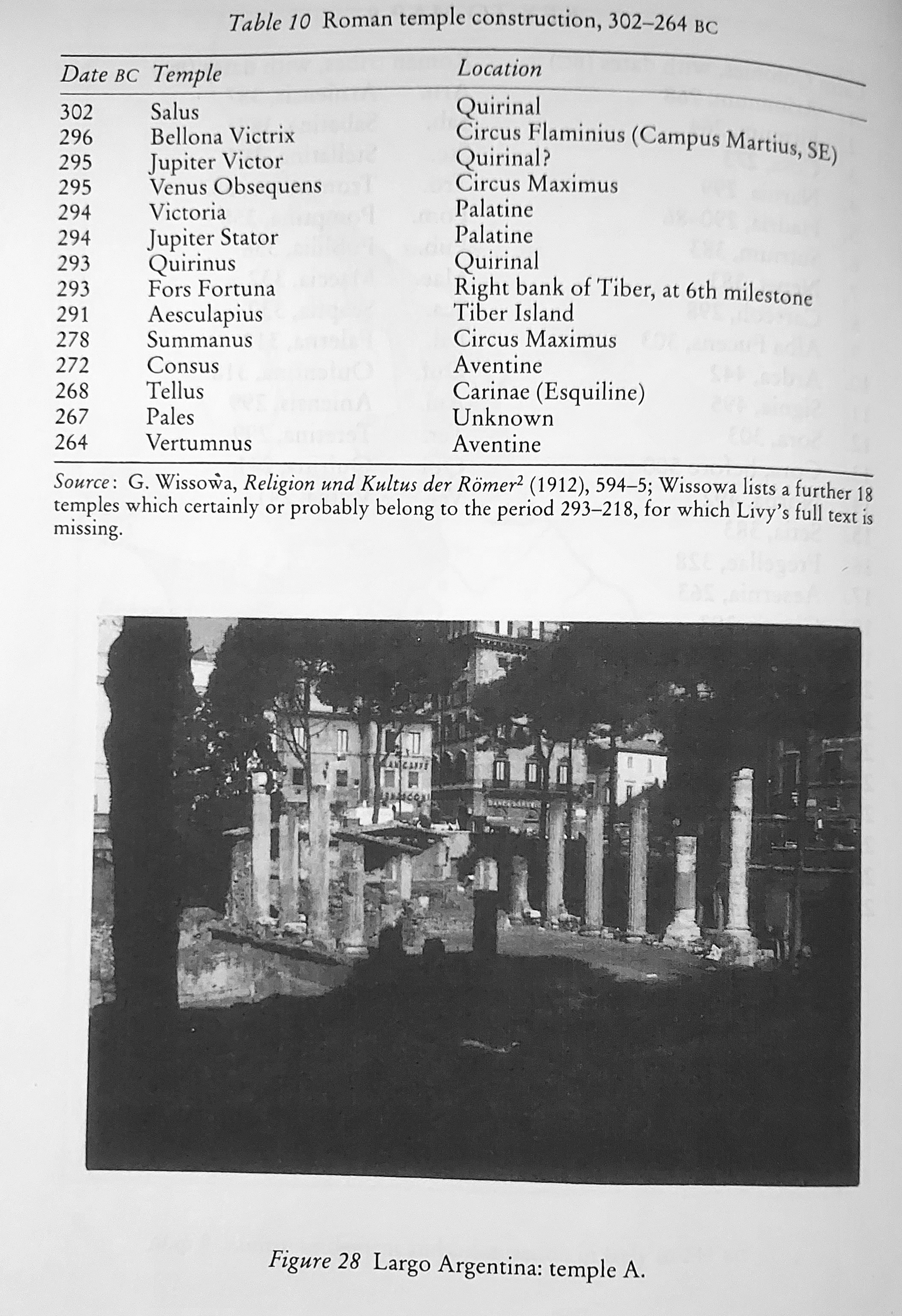

Temple construction at Rome, late 4th to mid-3rd centuries, from T. J. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (1995)

Roman temple construction in the mid-3rd century, from T. J. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (1995)

The most ancient were the haruspices who were responsible for animal sacrifice and interpretation, derived from Etruscan religious orthodoxy. They were representatives of the gods and their priests’ divination powers, perhaps similar to the Greek oracle model.[121] There were many arcane cults and ancient religious institutions, such as the ‘major’ flamines who were dedicated to the gods Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus (Romulus), the ‘lesser’ flamines covering other gods. There were the ten sacred men (decemviri sacris faciundis) who guarded the mysterious Sibylline Books.[122] The Vestal Virgins protected the sacred wooden Palladium, believed to have been saved from Troy by Aeneas and brought to Rome at the foundation.[123] A college known as the fetials (fetiales), who carried out diplomatic duties,[124] and were specifically responsible for the ceremonies related to war and treaty-making.[125]

The most important religious institution, politically, were the augurs, whose wide areas of responsibility made them vital for sanctifying public political and religious events.[126] The nine augurs (augures) were also responsible for collecting the many reports of natural and supernatural phenomena, everything from forest fires, lightning strikes on temple statues, earthquakes, the birth of hermaphrodites, to blood seeping from the earth and milk raining from the sky,[127] amongst other news and curiosities that were constantly being transmitted to the capital. The augurs were also responsible for defining sacred areas (templum) within the city, and establishing the city’s de-militarized religious boundary (pomerium).[128] The various information being received was known as the auspices (auspicia), and the augurs interpreted and processed all this information in their building, the auguraculum.[129] This was a profoundly significant role, as the taking of auspices preceded nearly every act of state.[130]

Roman Military Formations

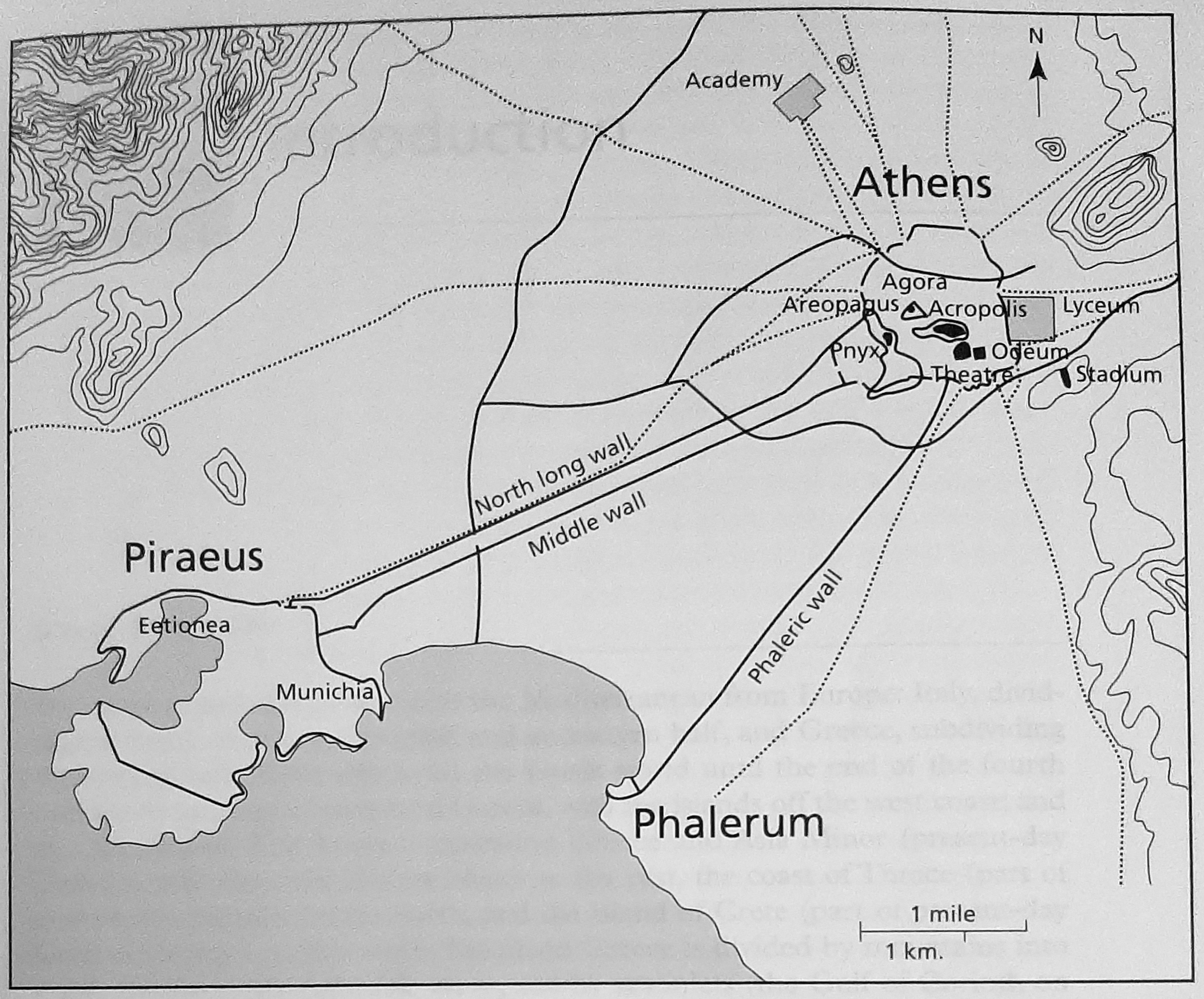

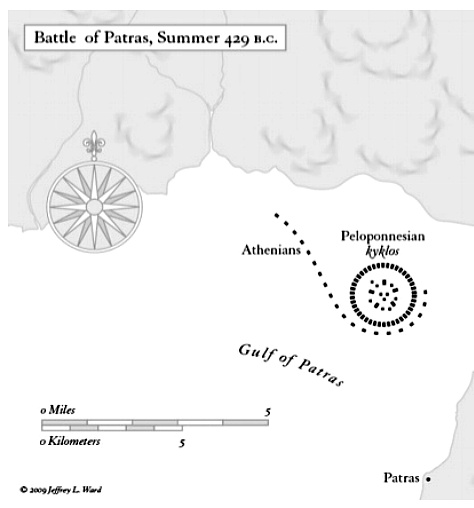

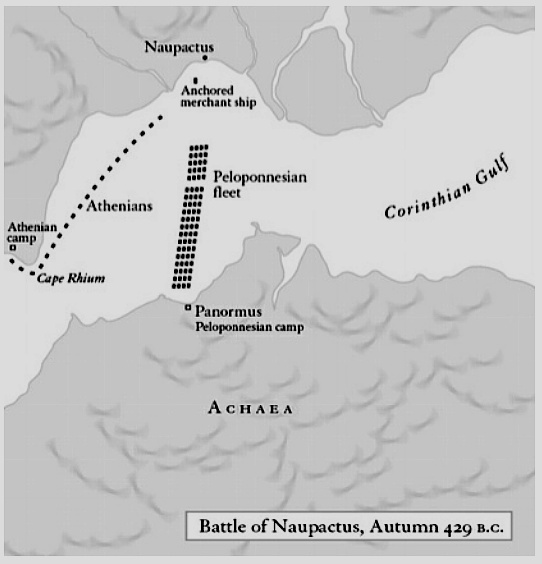

The largest military formation of the Roman Republic, after the Pyrrhic War and the conquest of Italy, was the consular army, two of which were marshalled every campaign season. Operating together, the consuls’ forces were about the equivalent of a modern army corps, and included 16,000-20,000 Latin infantry and 1,200 Roman cavalry (four legions), another 16,000 to 20,000 allied (socii) Italian infantry, plus 1,800 socii or Italic cavalry (four Alae Sociorum), for a total theatre force of 32,000-40,000 men and 3,000 cavalry. For comparative purposes, in 431 at the beginning of the Second Peloponnesian War when the total military capacity of Athens was about 32,000, the Peloponnesian army led by Spartan King Archidamus numbered between 40,000 to 60,000 men,[131] and the Macedonian army led by Alexander the Great at the outset of the Persian campaign numbered 44,000 infantry and 6,600 cavalry.[132]

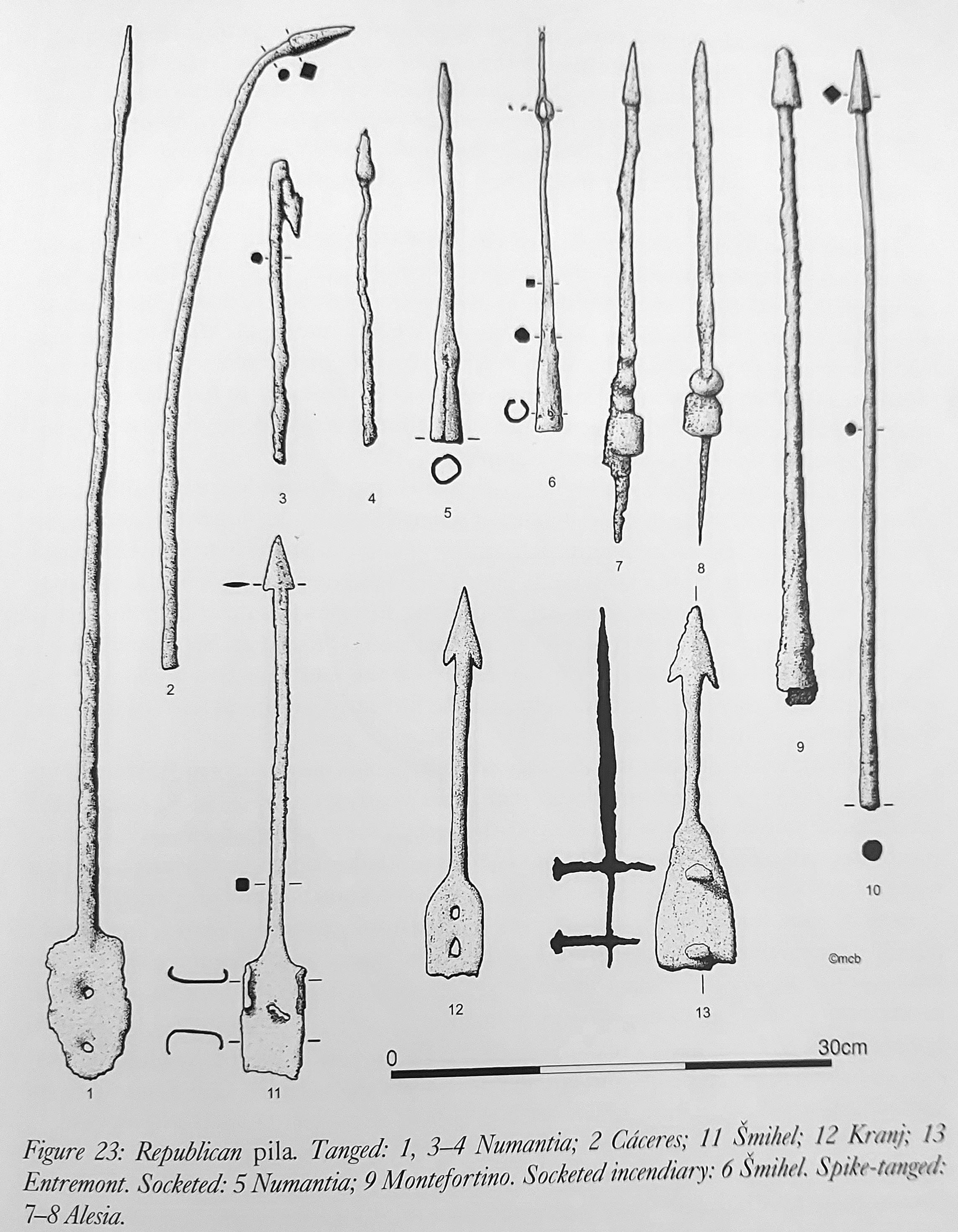

Roman republican pila, from M. C. Bishop & J. C. N. Coulston, Roman Military Equipment (2020)

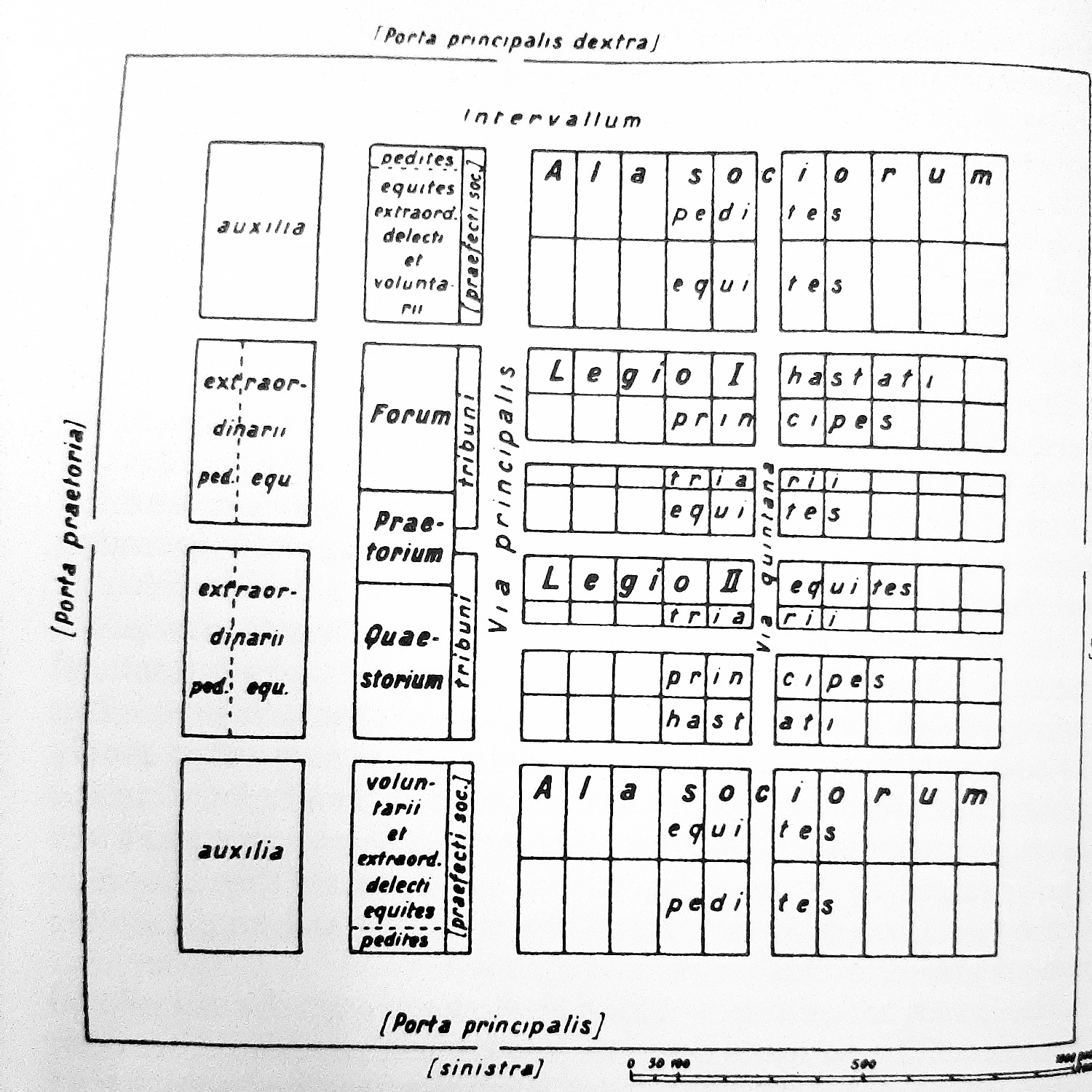

Each consular army was composed, in Louis Rawlings’ description, “of two legions of citizens, perhaps numbering around 8,000-10,000 infantry and 600 cavalry and two alae [“wings”] of allies, probably amounting to at least as many infantry (but perhaps many more in some situations) and three times the amount of cavalry.”[133] The consul’s headquarters was known as the praetorium. The staff of the consular command was a galaxy of officials and servants, each headquarters including 12 military tribunes, some of whom were tribune aerarii (paymasters),[134] six praefecti socium, two centurio primi pili, one quaestor – each was supported by an elected quaestor who formed a quaestorium and handled the legion’s finances and supply,[135] no doubt a number of legati, senior praefectus, optiones and the various attendants and accensi.

3rd century Roman legate, from Kiley, The Uniforms of the Roman World

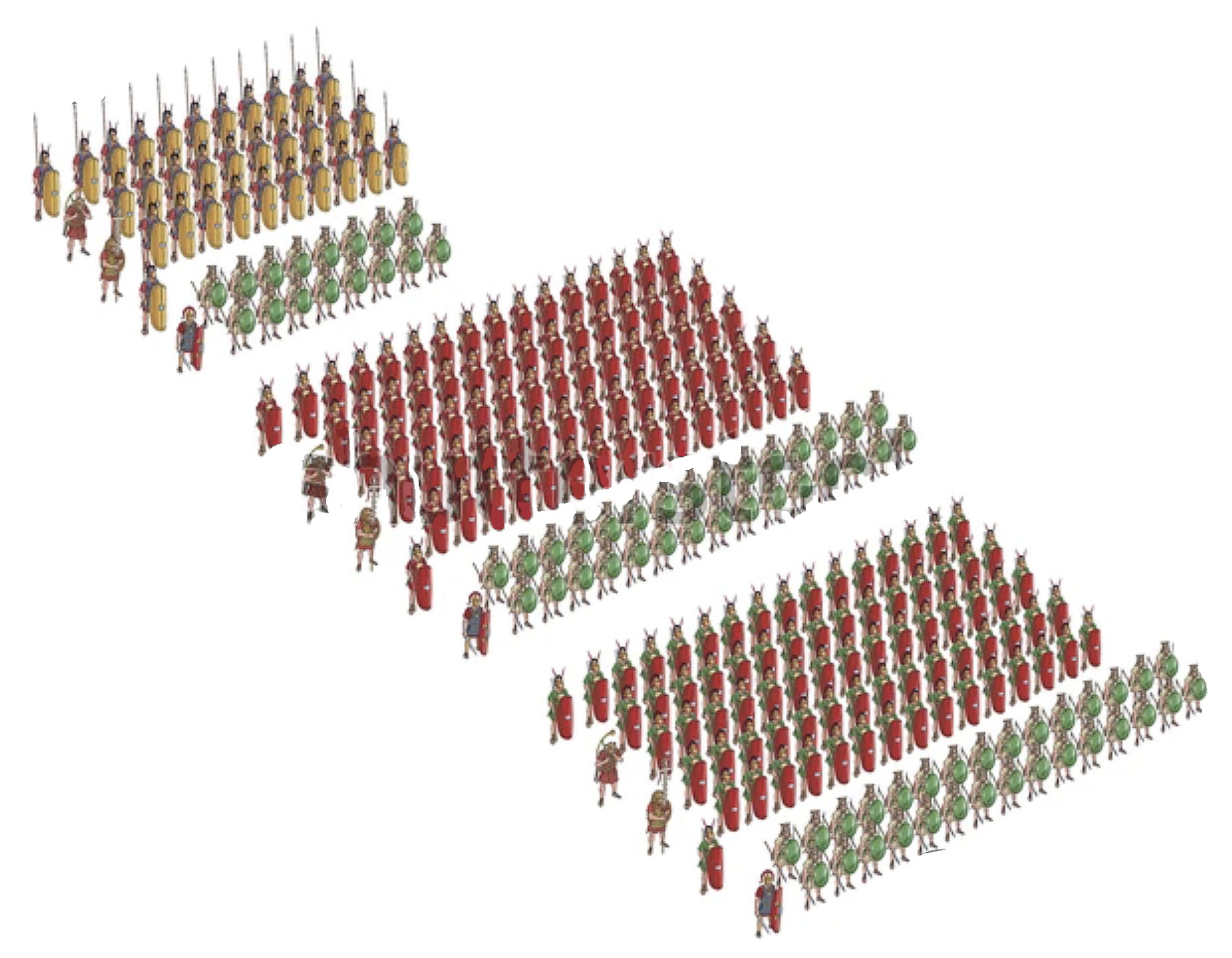

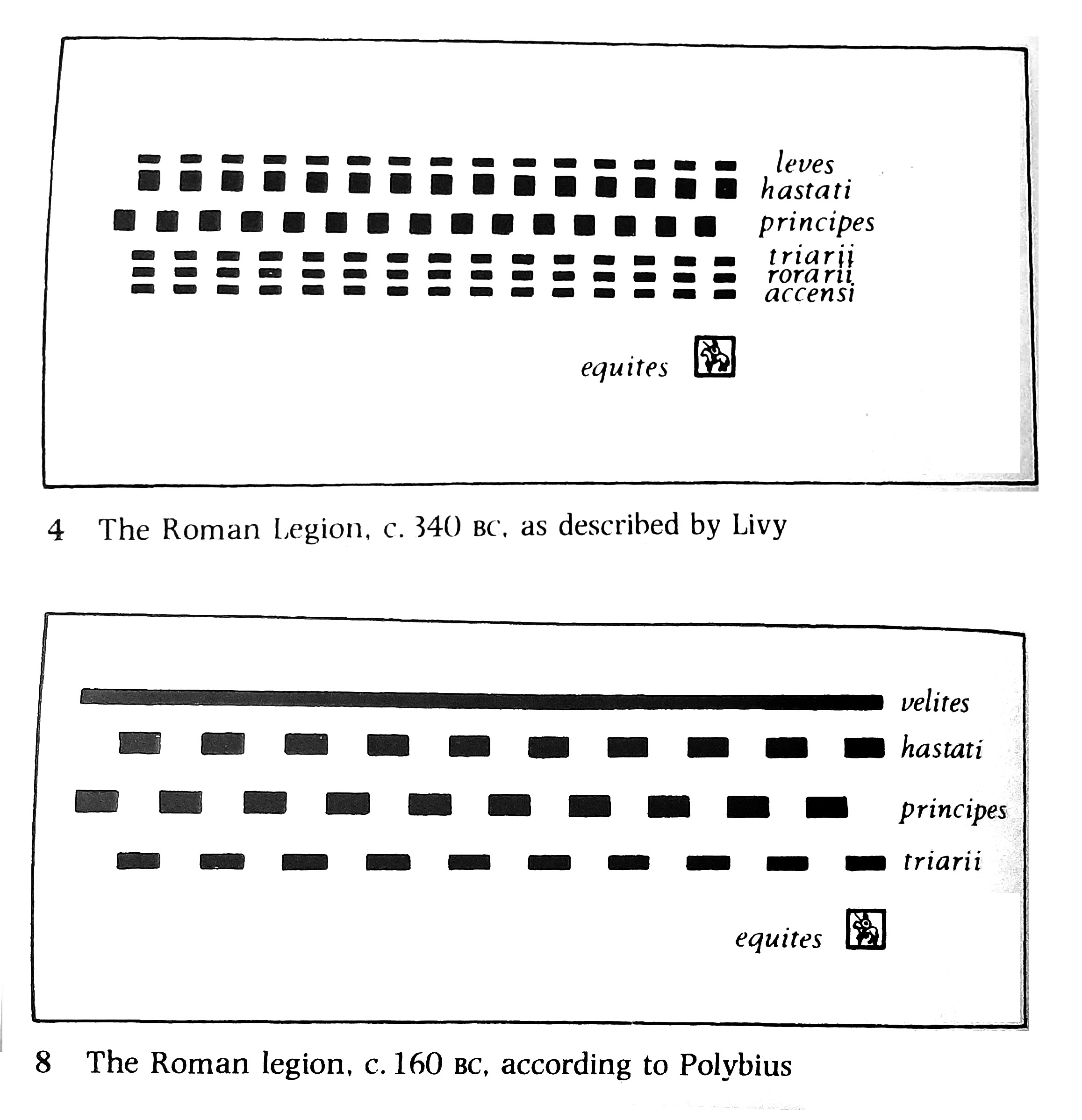

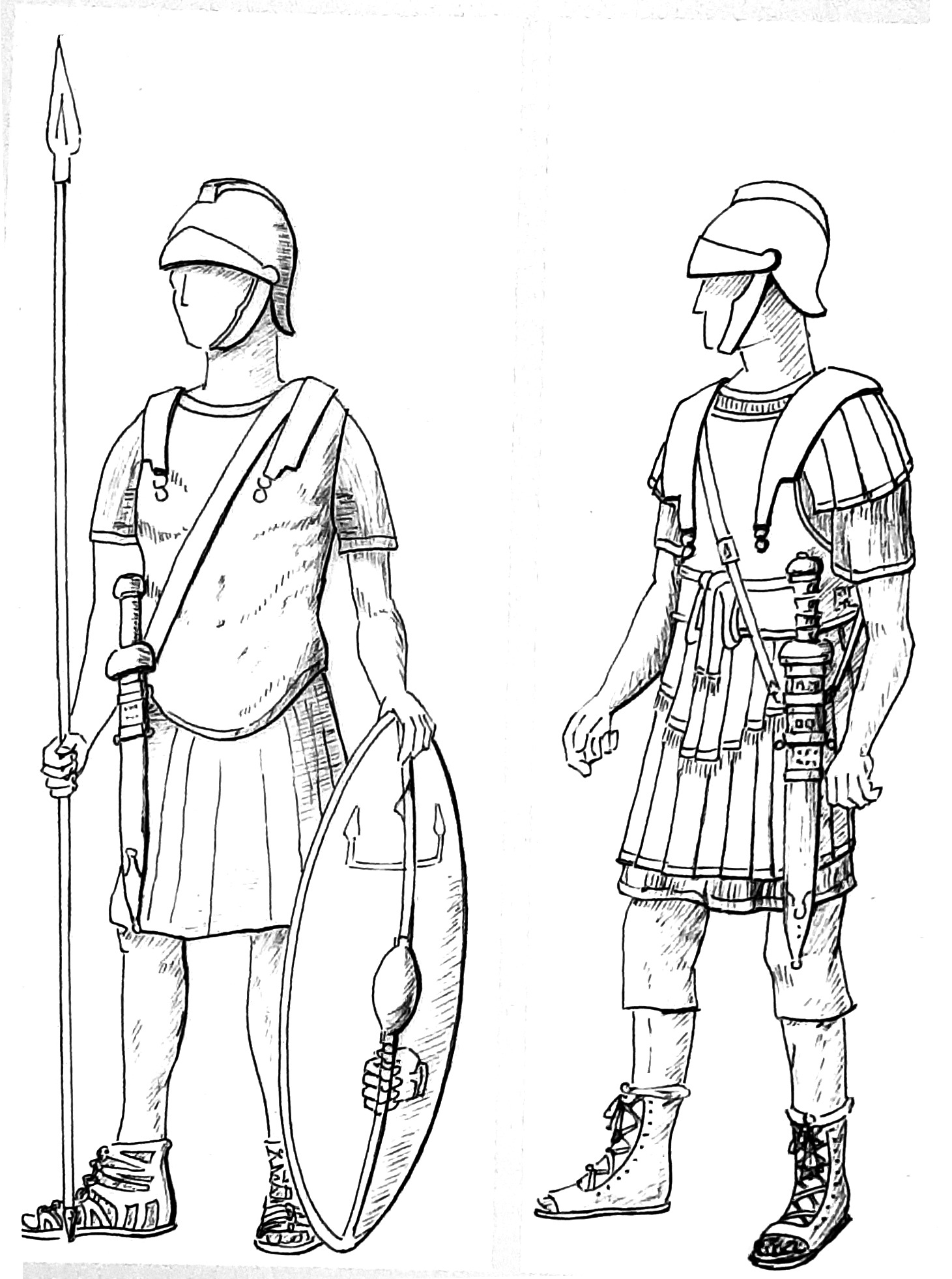

The Legion, of which two were the foundation of each consular army, was in turn composed of 4,200 infantry (600 triarii, 1,200 principes, 1,200 hastati and 1,200 rorarii or velites – javelins) plus 300 cavalry.[136] Each legion (I through IV) was commanded by veteran military tribunes of whom there were six per legion during the mid-3rd century: two pairs of three commanding each line of ten maniples (see below).[137] The military tribunes were elected directly by the comitia tributa when the army was marshaling on the Campus Martius, formalized in law in 311, and were supposed to be of the equestrian class (the knights), and having at least five to ten years of service experience.[138] Command was exercised by the tribune pairs rotating through two month intervals during the course of a six-month-long campaign season (April to September),[139] much as the consuls exchanged supreme command by passing the fasces every month, if not every day, when operating together.[140]

Kneeling Roman triarii, Roman princeps, Legionary, c. 220 BC, Roman centurion, 4th to 3rd century, Roman velite, c. 4th century, & javelin skirmisher c. 220, from Kiley, The Uniforms of the Roman World.

Mid-Republican legionaries, from Adrian Goldsworthy, The Complete Roman Army (2021)

The military tribunes were supported by legati, senators or magistrates in-between offices, such as former plebeian tribunes, praetors, quaestors or aediles (Cato the Elder was a legate after he had been consul). The legates, appointed to the military tribunes’ command, acted as delegates for the elected magistrates, controlling detached forces or garrisoning towns and cities. This was a sure-fire way for rising patricians to gain military experience without the heavy responsibility of legionary command, which was monopolized by the plebeians at any rate. The need for these officials certainly derived from the protracted campaign in Sicily, if not the previous century of warfare throughout Italy, although, as with the Roman cohort organization, they are not directly attested until after the First Punic War.[141]

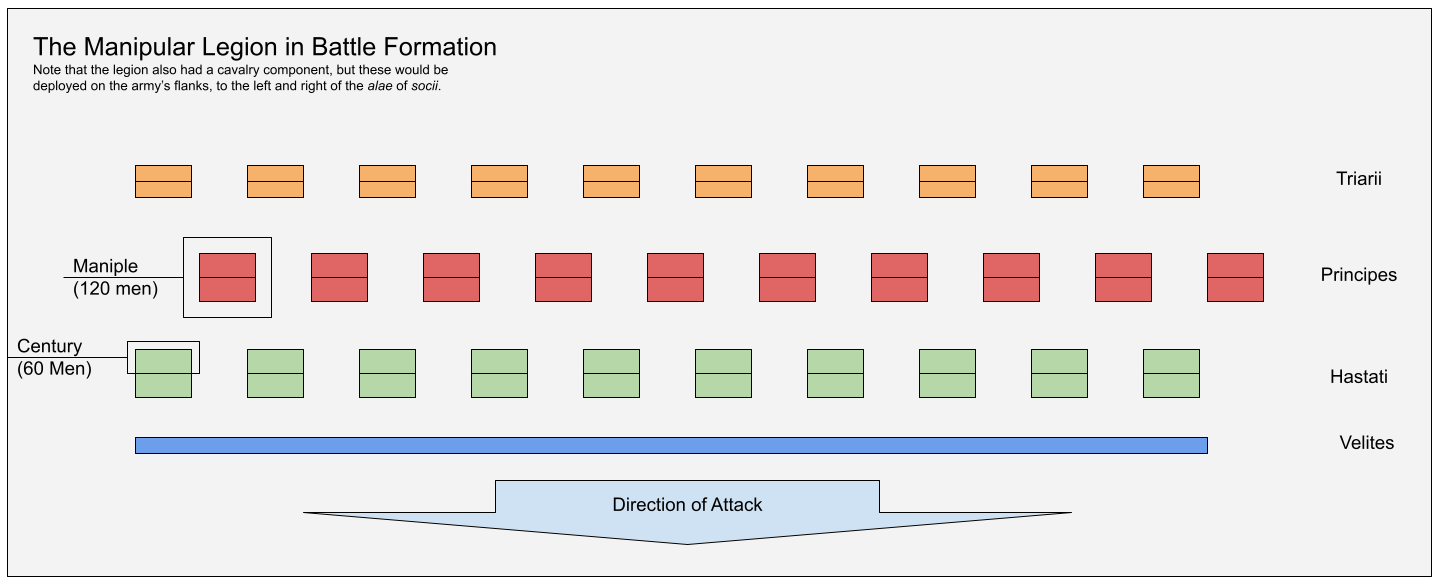

The basic infantry unit in the Roman Republican Army of this era was the maniple or ‘handful’, essentially a company of 120 (hastati and principes) or 60 (triarii), with attached 40-man javelin (velites) platoons,[142] which had evolved from the earlier centuriae formation of the city-state period.[143] Each 120-man heavy infantry maniple – there were 30 in a legion – was divided into two centuriae, platoons, each of these commanded by a centurion of whom the senior centurion commanded the maniple as a whole,[144] and their sergeants (optiones), who were in turn supported by a number of accensi, that is, attendants – runners and armour carriers.[145] The senior centurion of the legion, in command of the final right-hand triarii maniple, was known as the centurio primi pili or primus pilus and accompanied the legionary tribunes in command of the legion.[146]

Conjectural Roman Republican Manipular Legion

Example of Roman manipular legion ranks, triarii at rear, princeps in middle, and hastati at front, with skrimirshers interspersed between the line

‘Polybian’ legion, showing complete consular army with allies, from Adrian Goldsworthy, The Complete Roman Army (2021)

When deployed for battle the legion was divided into its maniples, each centuriae one behind the other (thus termed prior and posterior),[147] and the maniples arranged into their three lines by type, whether hastati, principes or triarii, each line consisting of 10 maniples. Battle would begin with a hail of javelins thrown by the numerous levy skirmishers that accompanied the heavier troops.[148] The 300 legionary cavalry were divided into 10 turmae of 30 cavalrymen, each commanded by a group of three decurions of whom one was the senior ‘leader of ten men’.[149]

Consular Army Camp, from Lawrence Keppie, The Making of the Roman Army (University of Oklahoma Press, 1998)

Evolution of the Roman Army, c. 340 BC to c. 160 BC, centuries to maniples from Lawrence Keppie, The Making of the Roman Army (University of Oklahoma Press, 1998)

The Italic Legions of the allies (ala sociorum), for their part, were more straight-forwardly organized into 10-15 cohorts (cohors) each comprising about 500 men.[150] Although Roman units after the war with Hannibal began to be formed into cohorts of 460-600 men, there is doubt that the cohort organization was adopted for Roman units proper prior to the Second Punic War since the maniple was so clearly the primary unit of organization.[151] Originally termed a turmae, each socii cohort was commanded by a praefectus, who was the elected local magistrate from whichever village or town the cohort had been assembled.[152] An elite contingent known as the extraordinarii was also marshalled by drawing from the best of all the socii cohorts.[153] The ala socriorum were commanded by Roman equestrians known as praefectus sociorum or praefecti socium, who were appointed by the consuls, three per allied legion.[154]

Manpower was supplied by the institution known as formula togatorum – a list of male adults – what historian Lazeby suggested may have been, “a kind of sliding-scale requiring so many men for the number of citizen soldiers raised in any year.”[155] Soldiers supplied their own weapons, armour, horses and servants, ranging from the elite equestrian equites, through to the breastplate or chain-mail and shield (scotum) armoured triarii and principes, to the strictly javelin (pilum) equipped citizen skirmishers (velites).

The Campus Martius of the 6th century Roman city-state

Campus Martius to the west of Rome, in the 3rd and 2nd centuries, from A Companion to the Punic Wars, ed., Dexter Hoyos (Wiley-Blackwell, 2015)

Rome in the 3rd century, from Penelope Davies, ‘Architecture’s Agency in Fourth-Century Rome’ in Making the Middle Republic, ed., Seth Bernard, Lisa Marie Mignone, and Dan-el Padilla Peralta (2023)

At the beginning of their term of office (the Ides of March during the First Punic War), the consuls summoned all the chief magistrates from all the Italic villages, towns and cities, and arranged the number of men to be levied for the campaign season that year.[156] The entire process of marshaling, arming and assembling could take time. However, if the levy numbers were already available at Rome beforehand, the army could be readied in as little as 15 days.[157]

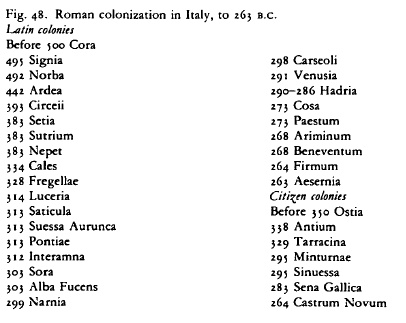

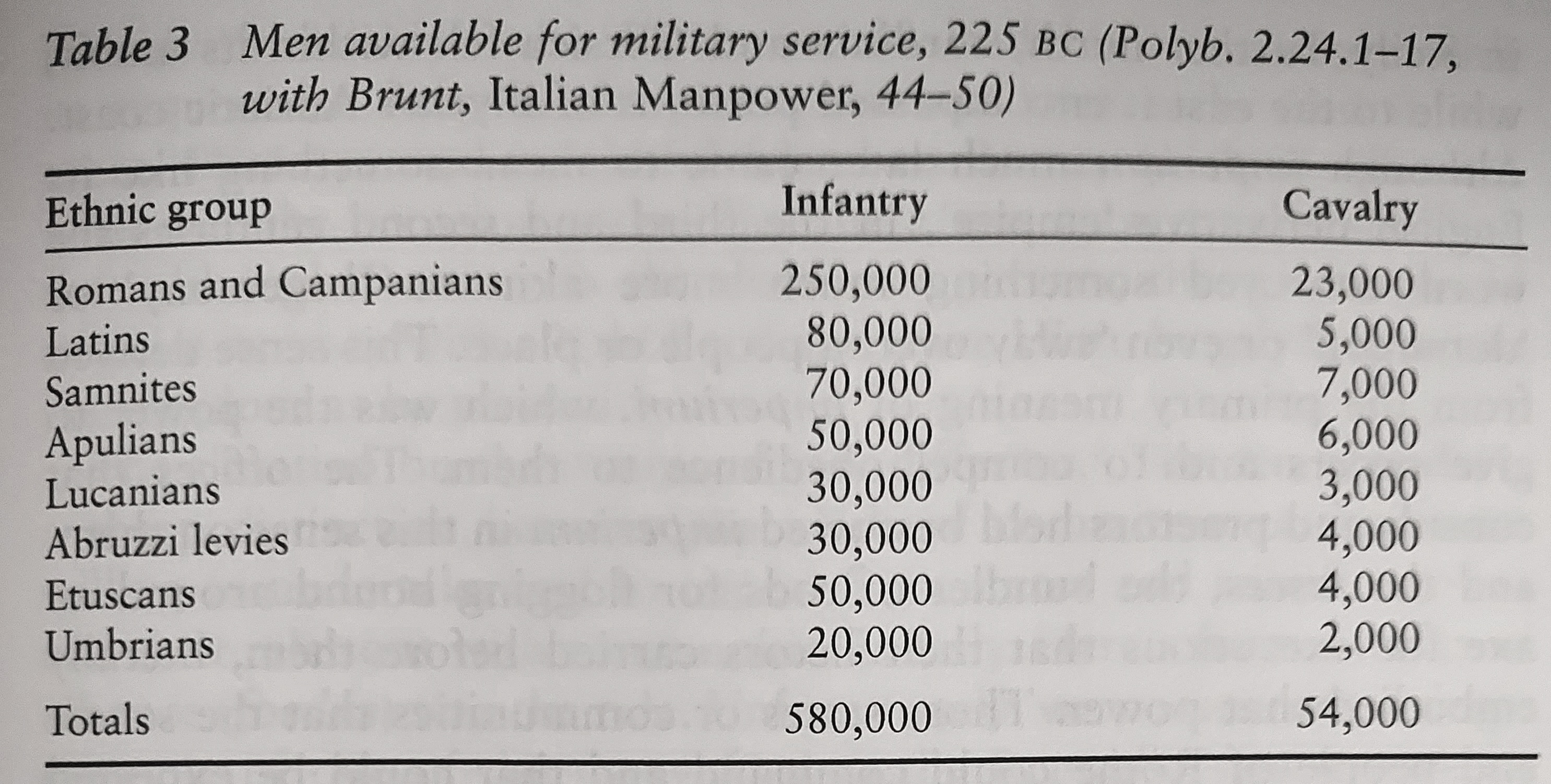

The census for 264 placed the adult male citizen population of Rome at 292,234, of whom anyone between the ages of 17 and 46 could be levied.[158] The total manpower of Rome and the allies was significant. 155,000 were called up for the Gallic invasion of 225, and Polybius’ total estimate, based off Fabius Pictor’s numbers for that same year, are likely close to what they had been at the beginning of the First Punic War, 770,000 (700,000 infantry and 70,000 cavalry).[159] The Romans could therefore draw on an immense supply of manpower for soldiery and oarsmen. The Carthaginians, in comparison, rarely fielded more than 20,000 of their own citizens under arms at any given time, and then only in dire circumstances.

List of Latin colonies, 334-263, same as T. J. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (1995)

Totals: 730,000 infantry and 72,700 cavalry

Figures showing size of Roman and allied manpower, near what it would have been in 264, derived from Polybius, from Gary Forsythe in A Companion to the Roman Army, ed. Paul Erdkamp (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011)

Roman and Allied (socii) manpower figures for c. 230, close to what they would have been in 264. From ‘The Army and Centuriate Organization in Early Rome’ by Gary Forsythe in A Companion to the Roman Army (2011) & Alternate figures from Rosenstein, Rome and the Mediterranean (2012)

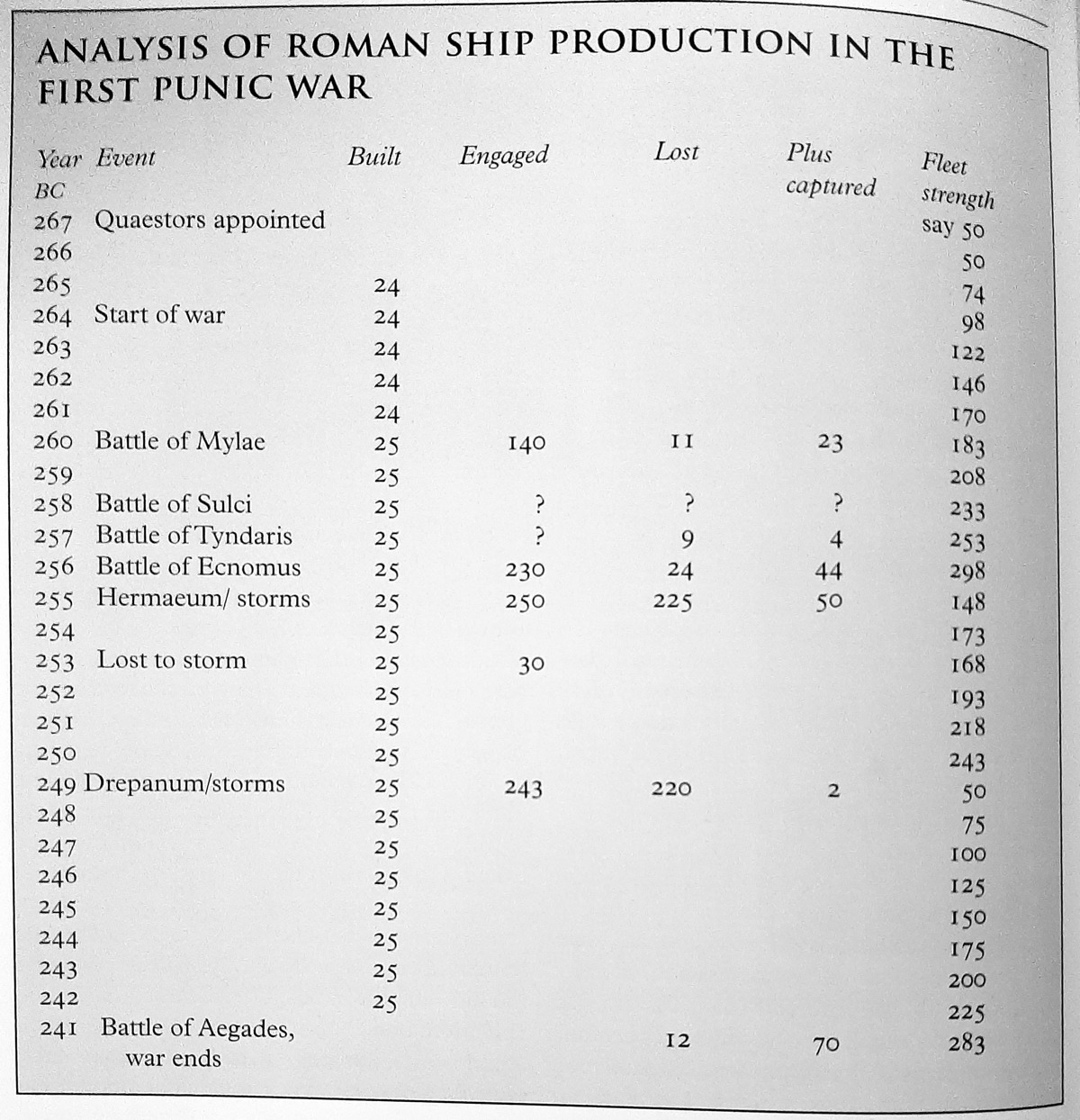

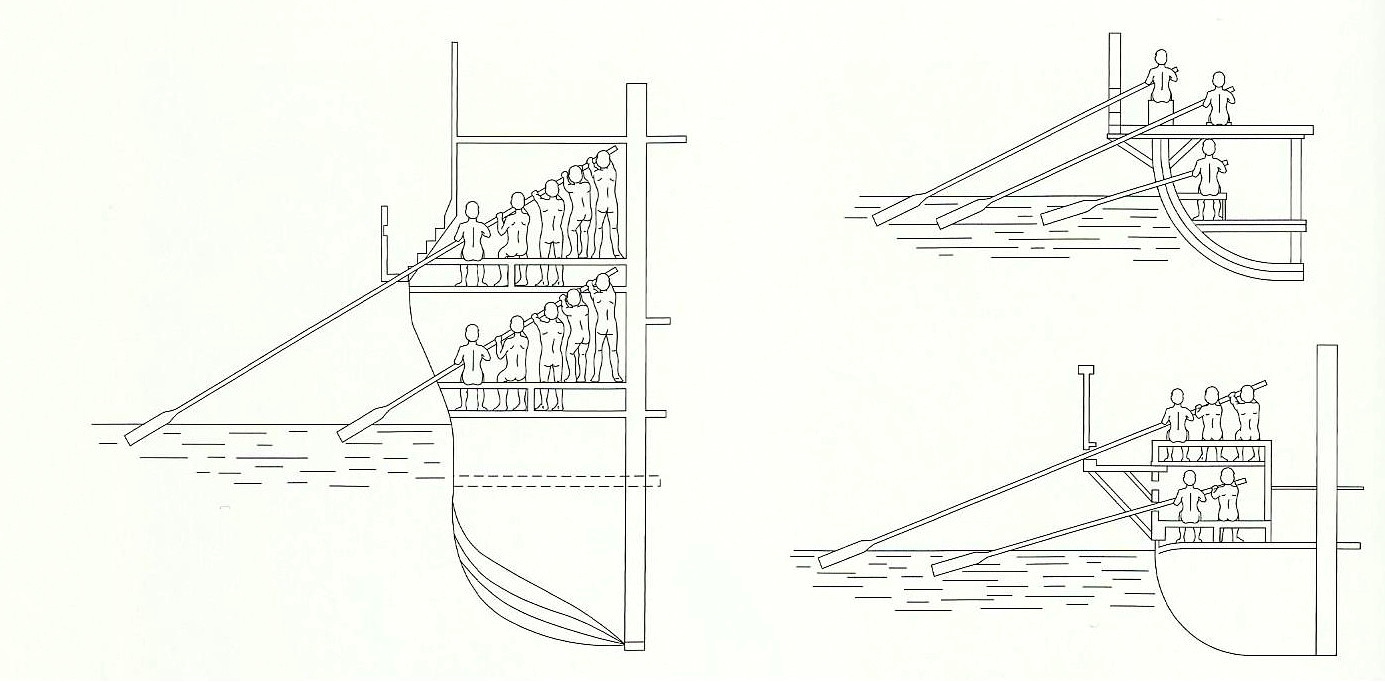

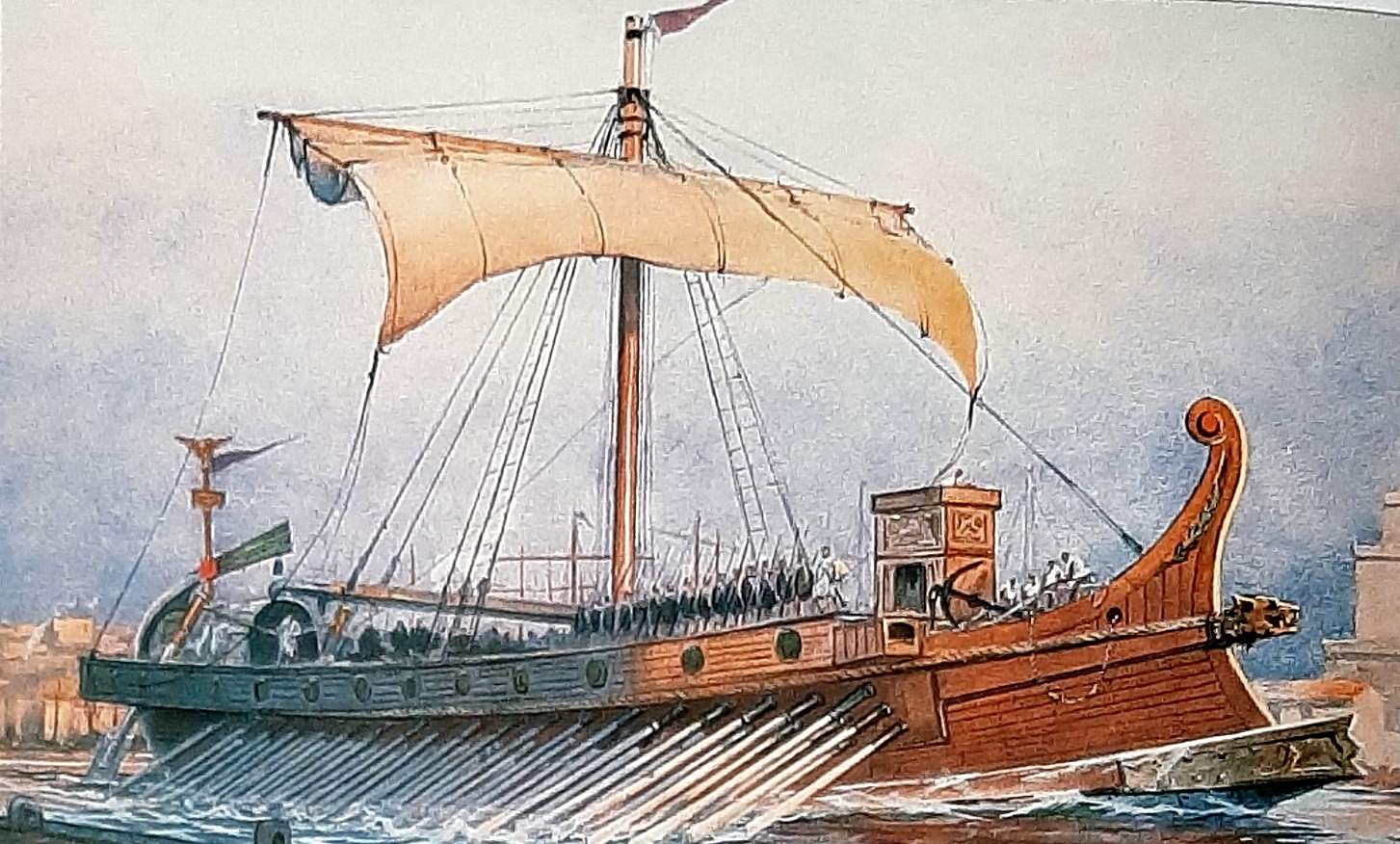

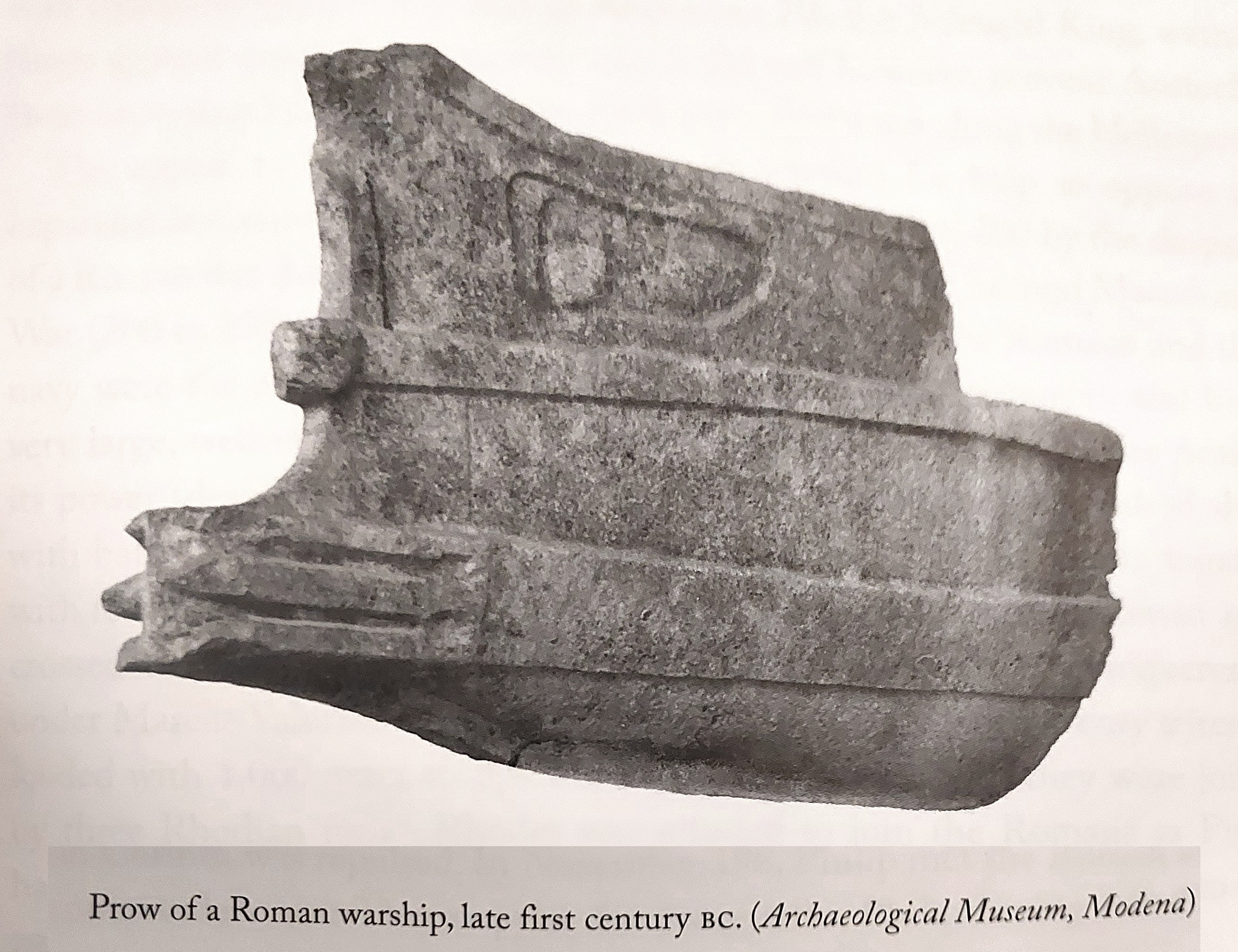

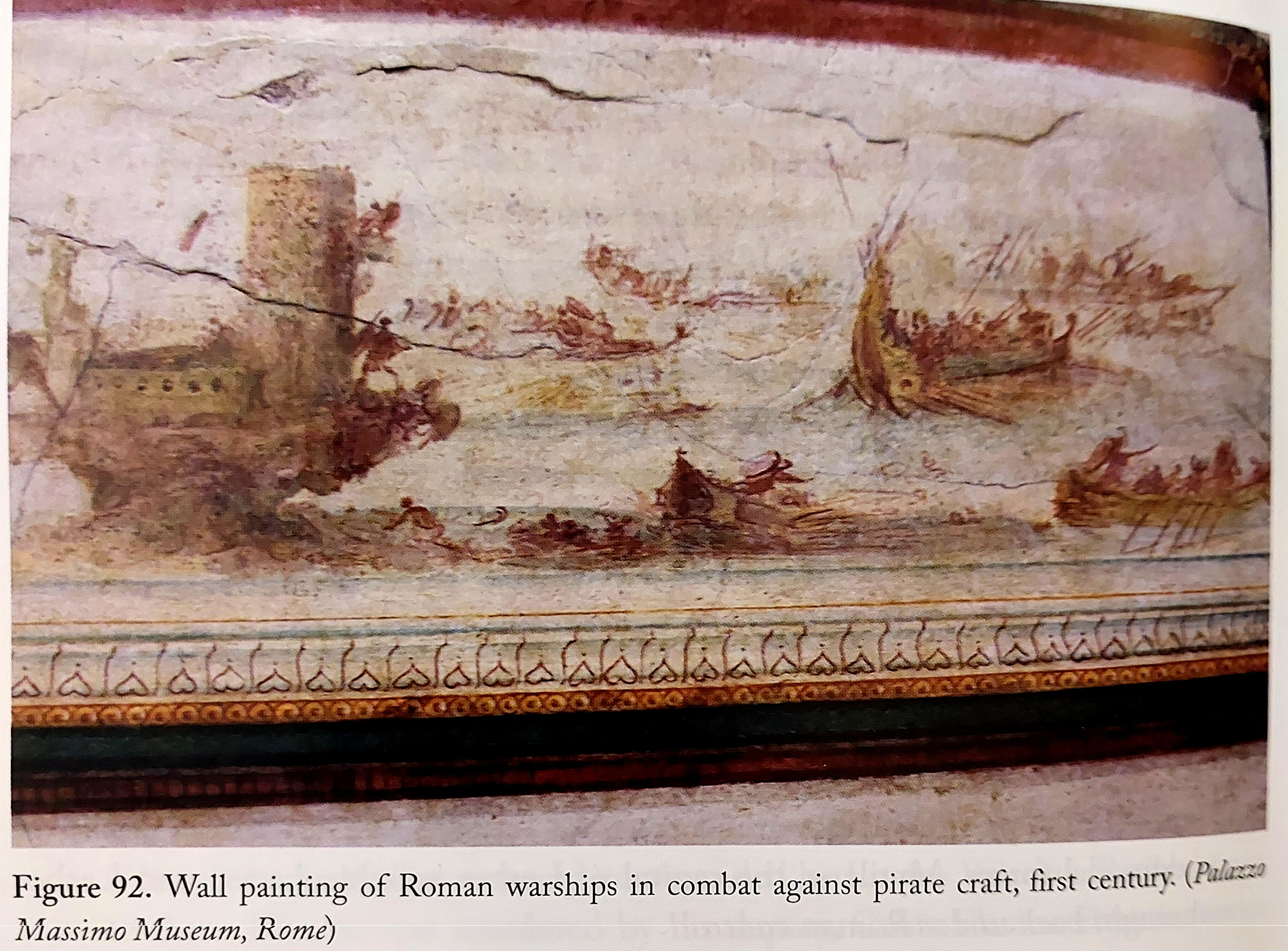

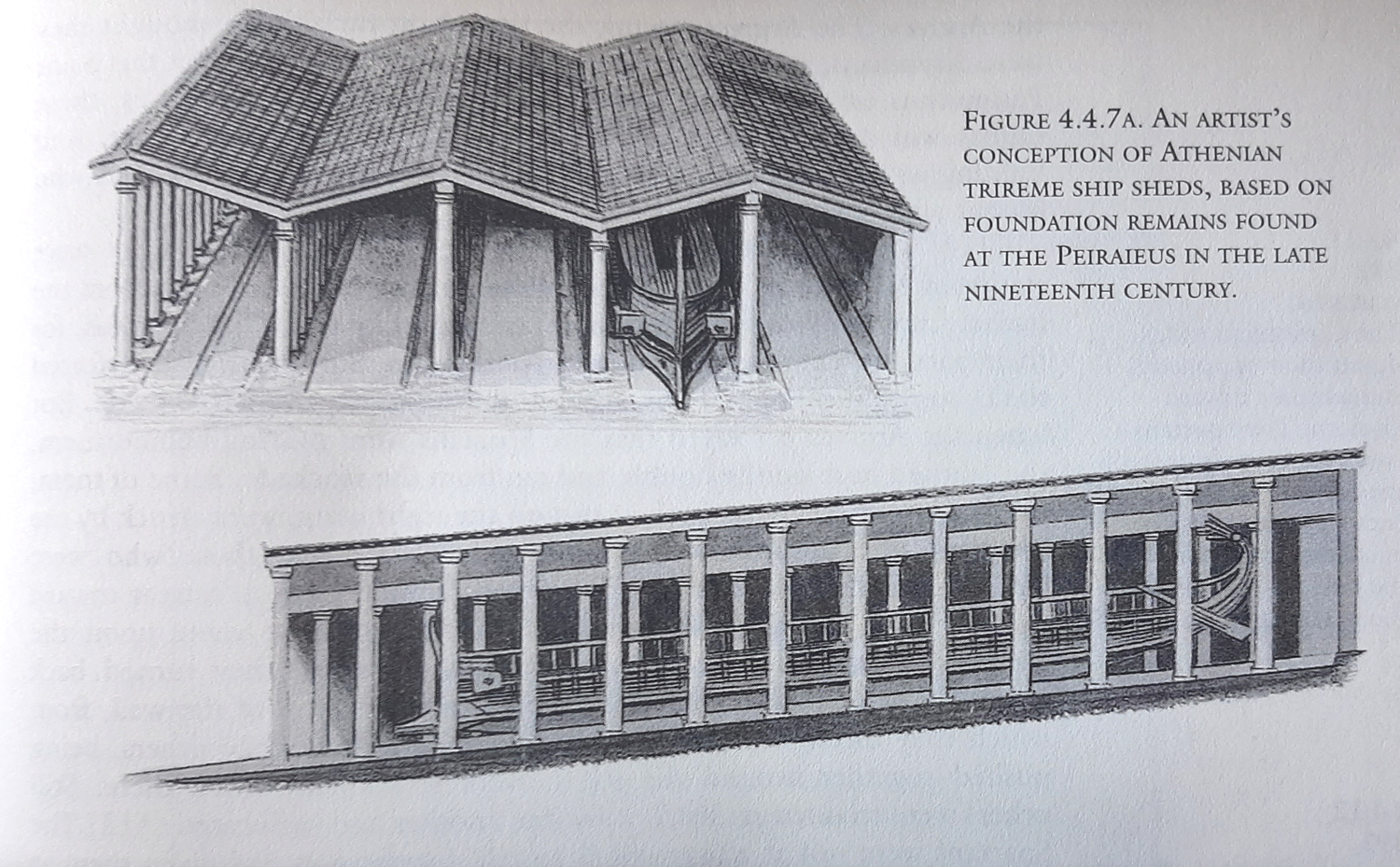

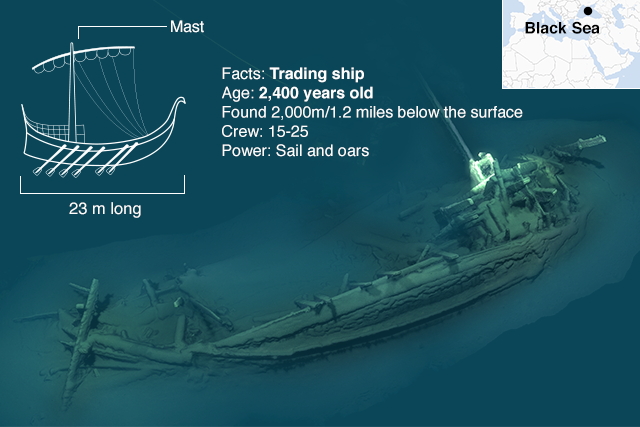

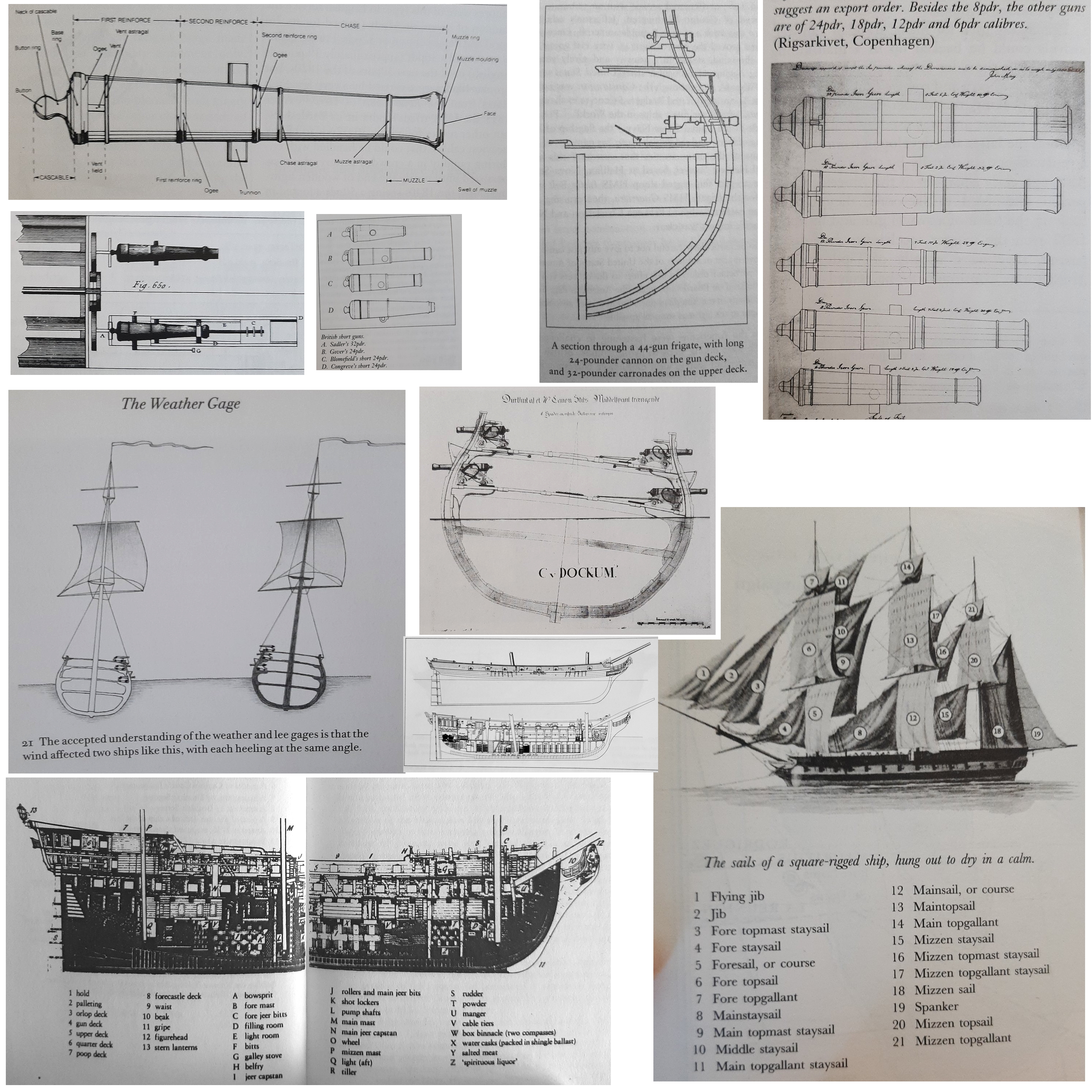

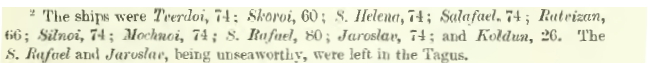

The earliest Roman Navy had been established in 311 as a small constabulary and anti-piracy force of no more than 20 ships, two squadrons of ten commanded each by a duumviri navales.[160] The coastal settlements, socii navales, were requested to provide ships and marines when a fleet was needed.[161] In 282 during the Pyrrhic War, when the Romans sent one of the squadrons to Tarentum, the Tarentines sailed out and sank four or five of the Roman galleys and captured one,[162] and thereafter – by 278 at the latest – the Romans primarily relied on their allies for transports and small ships.[163] Liburnians, light warships from Liburni, were especially favoured, as were fifty-oared penteconters from the Tarentines and Locrians, Elea and Naples.[164] The duumviri navales also sailed a fleet against the Sallentines in 267.[165]

Carthaginian Institutions

Aristotle, and later Mommsen, perceived the Carthaginian government as an oligarchy, the latter describing it as a “government of capitalists” representing the most powerful merchants, planters and guild leaders.[166] What is clear is that judicial and financial, if not legislative or military power, was concentrated in a select body representing an aristocratic tradition. Mommsen contrasted the Carthaginian empire with Rome by observing that whereas the Roman citizenship was gradually being extended across Italy, “Carthage from the first maintained her exclusiveness, and did not permit the dependent districts even to cherish a hope of being someday placed upon an equal footing.”[167] Scullard described the Carthaginian government as a timocratic oligarchy, decidedly ruled by traditional aristocratic factions, often monopolizing public positions such as was done by the powerful landowning and commercial families like the Magonid and Barca who were perfectly willing to use their financial power to buy their way into public office,[168] as Aristotle reminds us.[169]

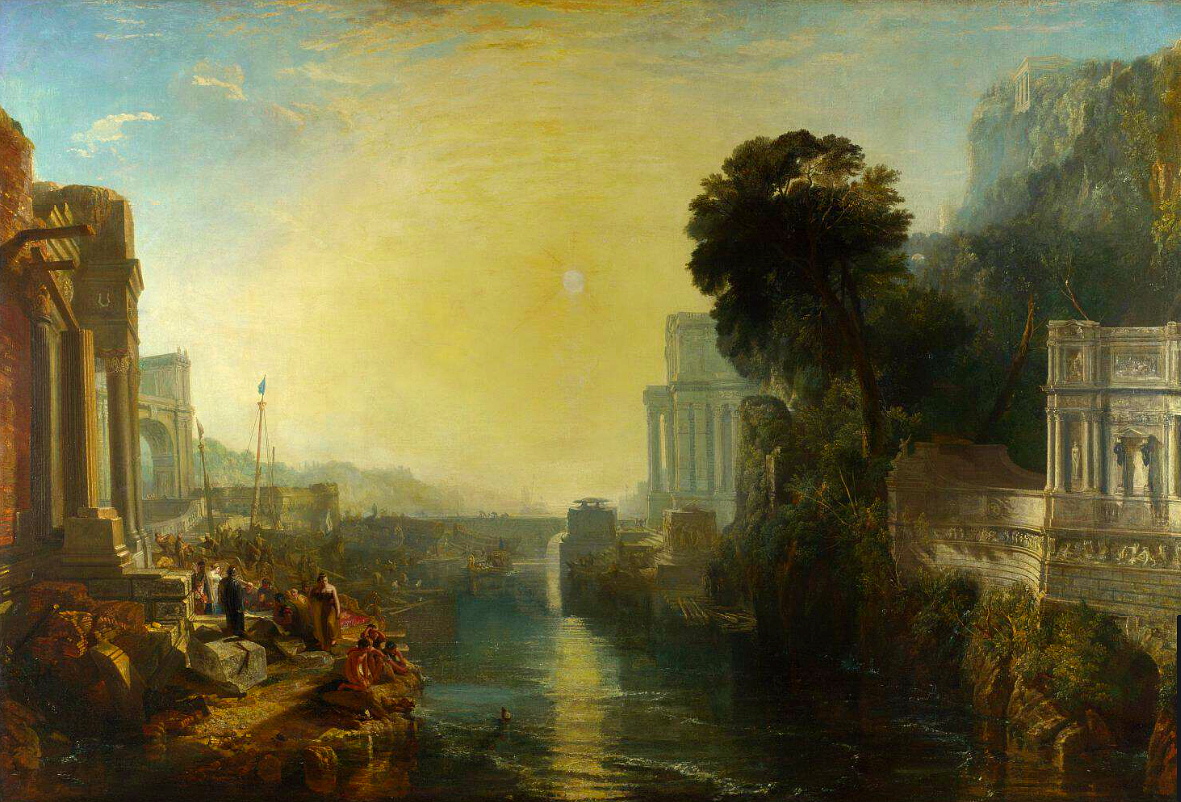

Joseph Turner’s 1815 painting of Dido building Carthage, scene from Virgil’s Aeneid.

Carthaginian empire before the First Punic War, 264, from “Carthaginian Casualties: The Socioeconomic Effects of the Losses Sustained in the First Punic War” MA Thesis by Laura Valiani (2016), & Rome and Carthage c. 264

As was the case in Rome, power in Carthage was constitutionally divided between the monarchical, aristocratic, and popular powers.[170] Like the Spartans kings, or Roman consuls, there were two monarchs, who in the Carthaginian case were known in Latin as suffetes or judges,[171] and who possessed judicial and legislative powers. Like the Roman consuls these magistrates held office through annual elections rather than hereditary fiat.[172] The legislative power was vested in an aristocratic Council consisting of some several hundred members who were annually elected and were responsible for the day-to-day business of the city.[173] Like the Spartan’s gerousia,[174] there was an inner ‘Council of the Ancients’ of 28-30 who advised and kept watch on the annually elected monarchs.[175] Collectively the Council of the Ancients, in conjunction with the kings, had the power to make law, war and appoint generals.

Carthaginian general, from Kiley, The Uniforms of the Roman World

The entrenched power of the clans was represented by the Tribunal of the One Hundred and Four (or One Hundred) Judges, appointed for life, all ex-Councilmen, being similar in this respect to the archaic power of the Athenian Aeropagus. Aristotle considered the Judges, along with the Carthaginian Council’s intractable corruption and office buying, as the most oligarchic element of the city-states’ constitution.[176] Mommsen described the Judges as “the main bulwark of the Carthaginian oligarchy,”[177] their function being to scrutinize and persecute public officials and military commanders for constitutional breaches or poor generalship.[178] The Tribunal of One Hundred and Four was appointed by the pentarchies or quinquevirates, the Boards (or Colleges, or Committees) of Five, who were powerful elder statesmen with control over both the city’s financing and its courts, somewhat comparable to Rome’s censors.

The popular power was represented by the assembly of the people, responsible for collective civic matters and the election of magistrates; far short of the war powers of the Roman comitia.[179] In the Carthaginian case the assembly was used primarily for discussion (and in a city of hundreds of thousands this discourse must have been considerable),[180] wherein matters were taken up from the Judges and Council, or tabled from amongst the speakers themselves.[181] For our purposes it is enough to observe that democratizing reforms at Carthage would have to await the conclusion of the Second Punic War, after which Hannibal Barcas himself limited members of the Tribunal of a Hundred and Four to no more than two year terms.[182]

Iberian or Celtic light, medium, and heavy infantrymen, & Balearic slinger from Kiley, The Uniforms of the Roman World

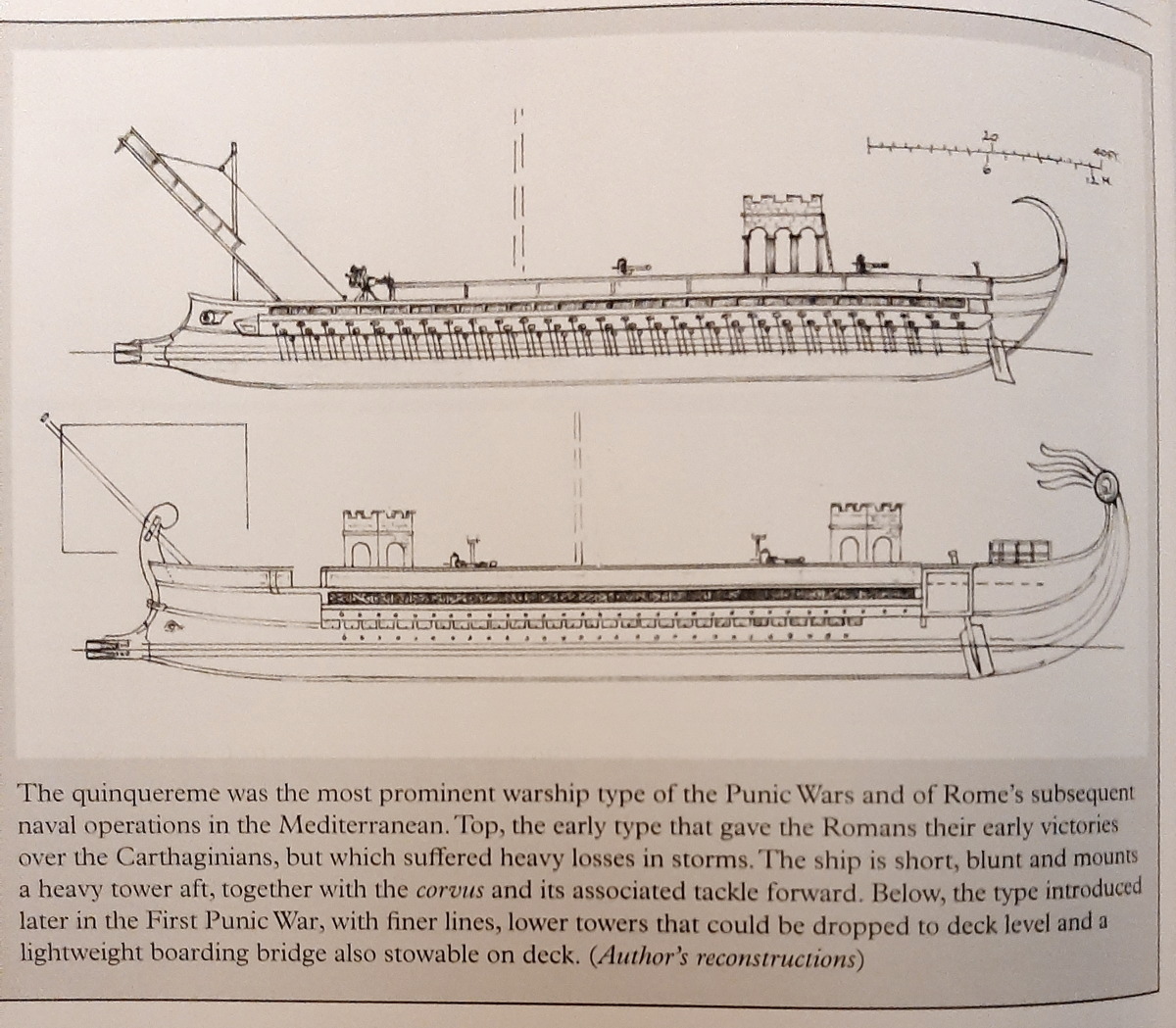

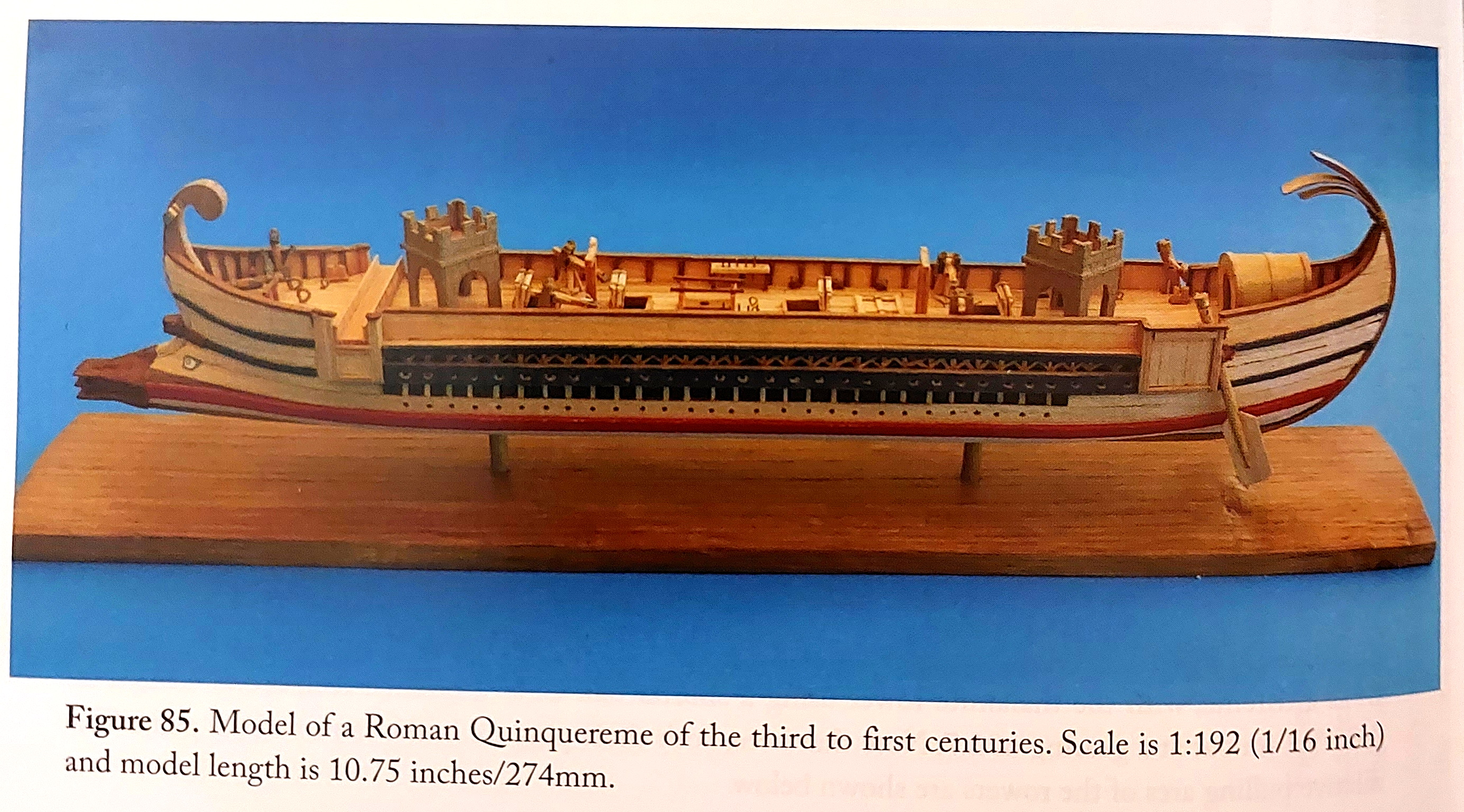

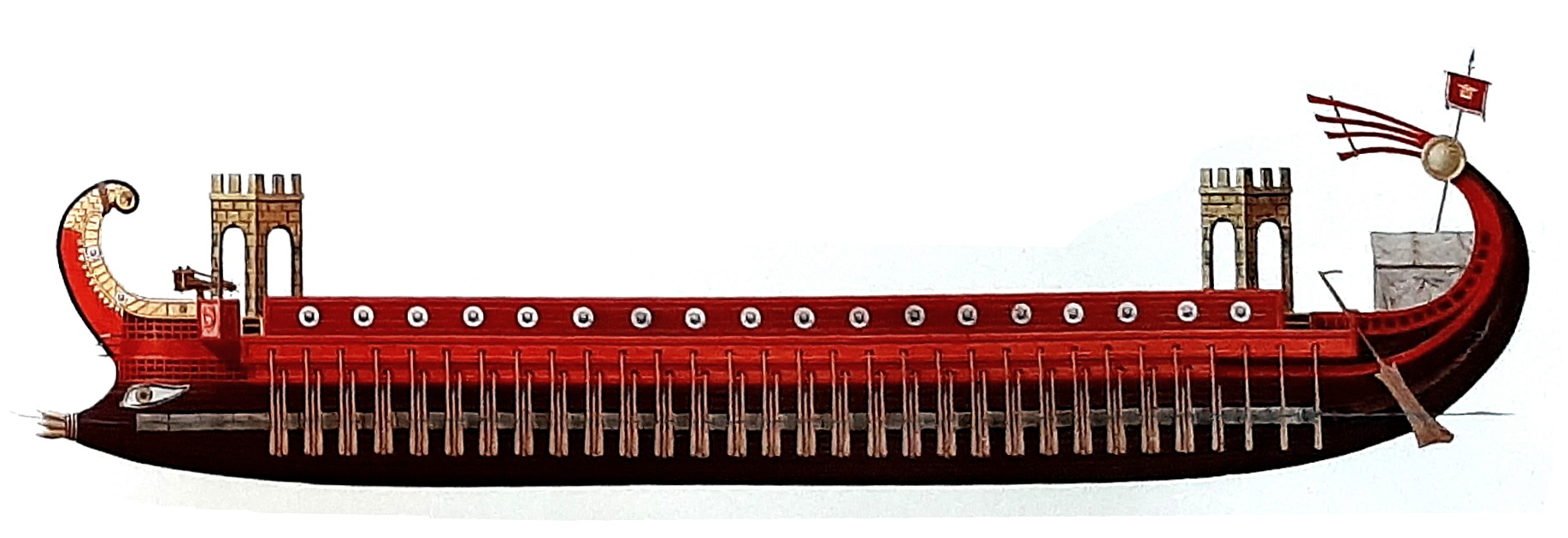

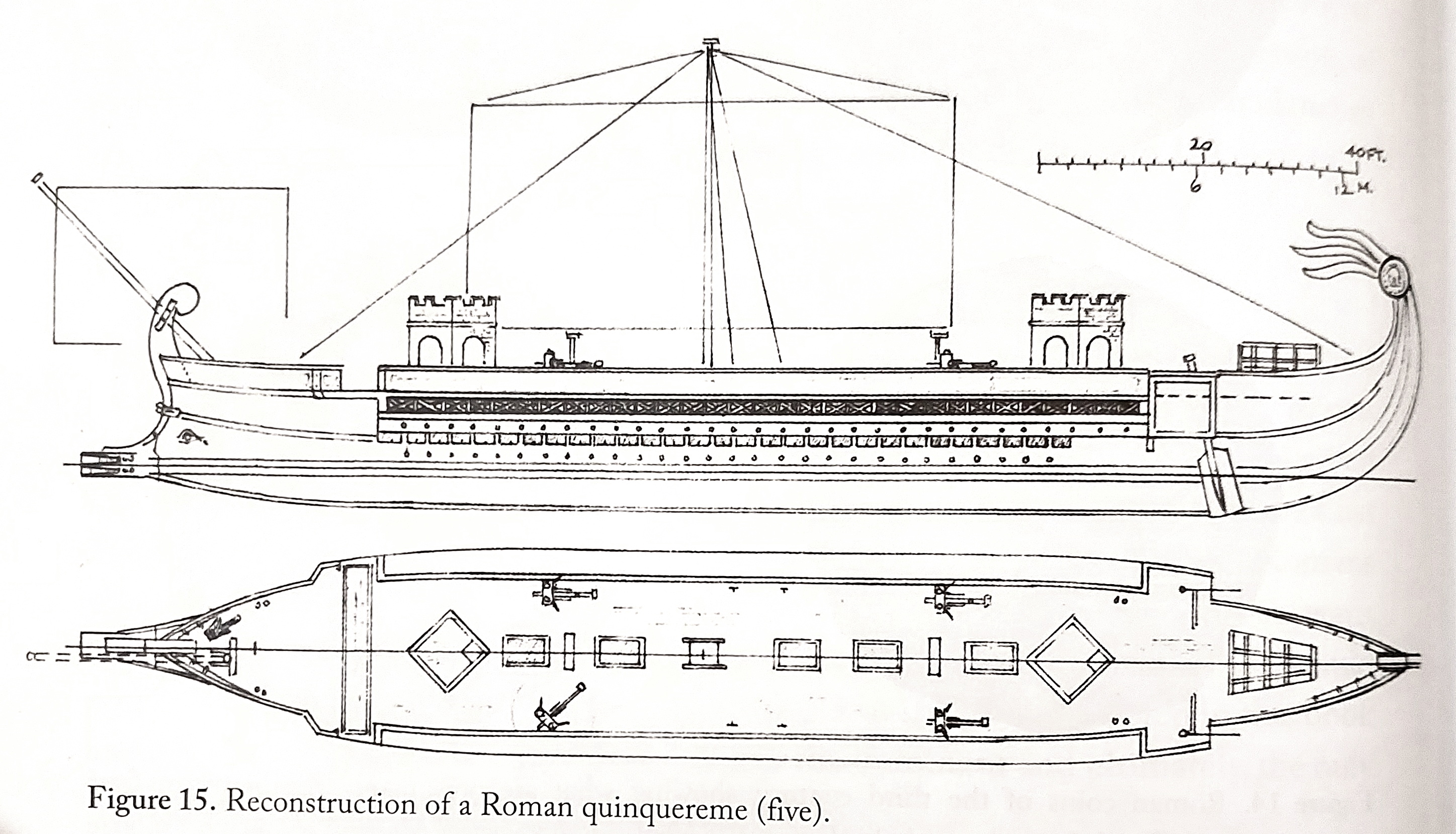

Carthaginian generals were usually reliant on mercenaries and their various Libyan, Sicilian, Sardinian, Iberian, Celtic, Italian, Greek and Numidian allies, and only deployed their own citizen-soldiers in dire emergencies, when as many as 40,000 citizen hoplites could be raised in an emergency, although this citizen levy was invariably of questionable quality.[183] The army was composed of elements from across the empire: The famous Numidian cavalry, Spanish and Celtic, Gaulish, mercenaries, and the Balearic slingers,[184] and there were 4,000 horses kept in Carthage itself, along with stalls for as many as 300 war elephants.[185] The Punic Navy was composed primarily of quinqueremes,[186] numbering in the hundreds.

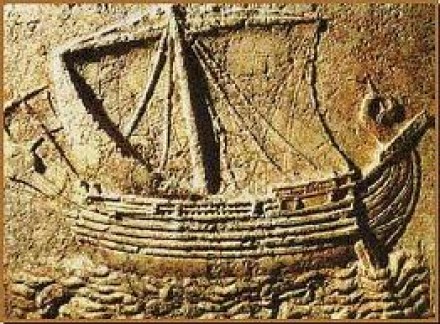

Reliant on maritime trade and thus a kind of thalassocracy, in 264 Carthage possessed incomparably the more experienced Navy and merchant fleet,[187] often crewed by the citizenry itself. The city’s generals, admirals and magistrates, like the Athenian strategoi at the conclusion of their commands, were brought before the Tribunal of the Hundred and Four judges where their command was then scrutinized.[188] This kind of scrutiny of office holders was popular in the Greek, Hellenic and Roman worlds and they were practiced on occasion as audits of Roman officials, and in Laconia conducted by the Spartan ephors, as well as at Athens where formal magisterial debriefings and disclosures where known as euthynai.[189]

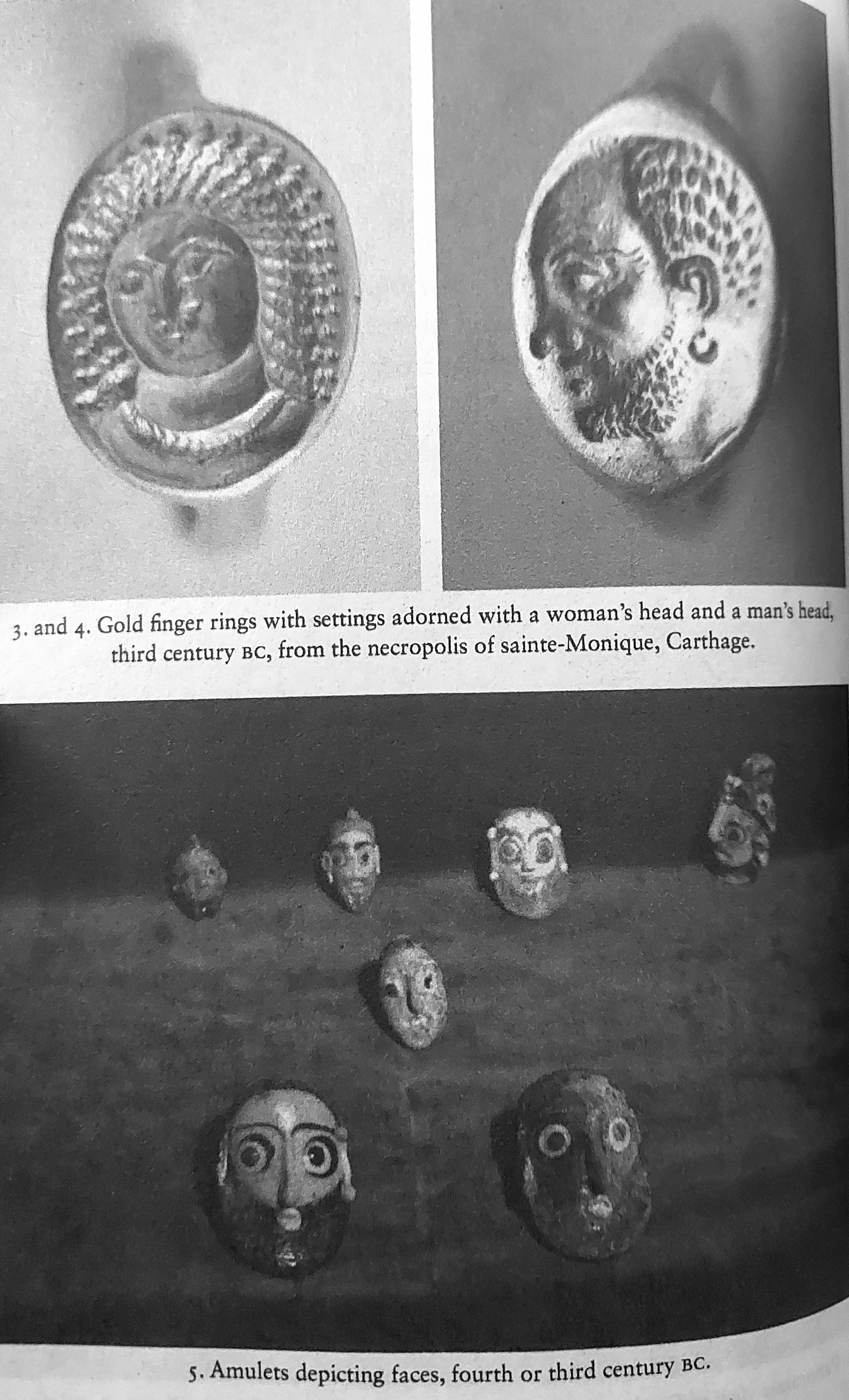

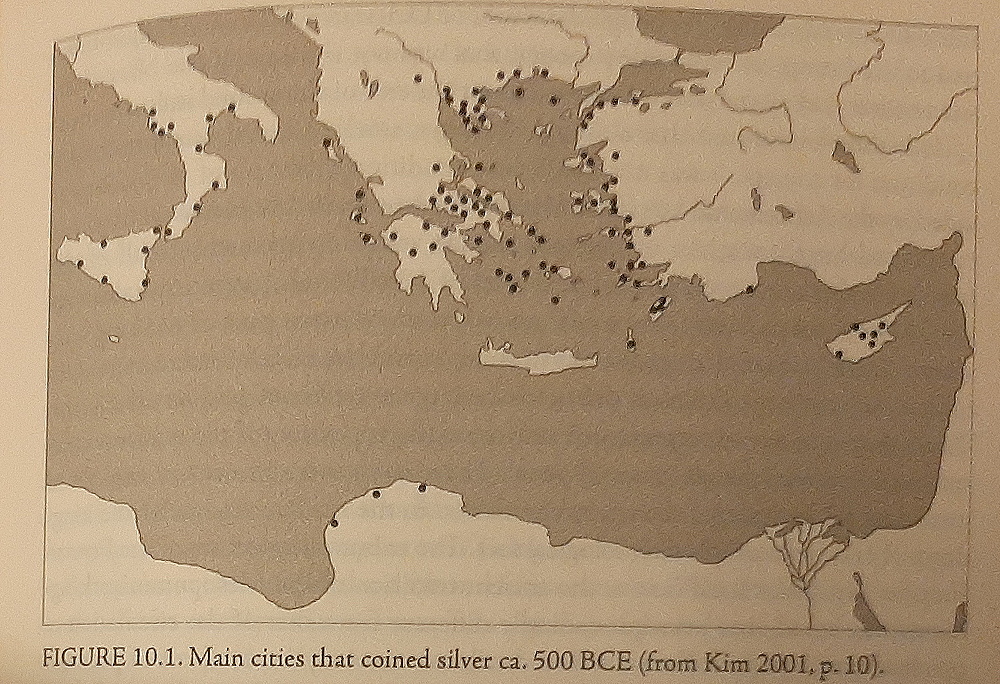

Carthage was already a fabulously wealthy trading entrepôt by the mid-5th century, and Carthaginian agricultural practice and animal husbandry in the Libyan hinterland were respected in both Rome and Greece (in particular the agricultural manual of Mago),[190] and was a major producer of horses, oxen, sheep and goats.[191] Carthage was also a supplier of salt to Italy, a significant producer of artisanal products, and an exporter of wheat, oil, food-stuffs, textiles, horses and slaves.[192] Olives grew plentifully at the coastal Sahel region.[193] Carthage exported fine wares such as carpets and cushions to Greece.[194] As with the Sardinian silver mines under Carthaginian control, ingots mined from southern Spain were of considerable value, and the coastal cities, former Phoenician colonies such as Gades, were dominated by Carthage.[195] Considering that the silver mines at Larium were enough to finance the Athenian empire,[196] the size and wealth of the Carthaginian polis, controlling as it did several such mines, is evident.

Rings and amulets from the 4th and 3rd centuries, from Richard Miles, Carthage Must Be Destroyed (2010)

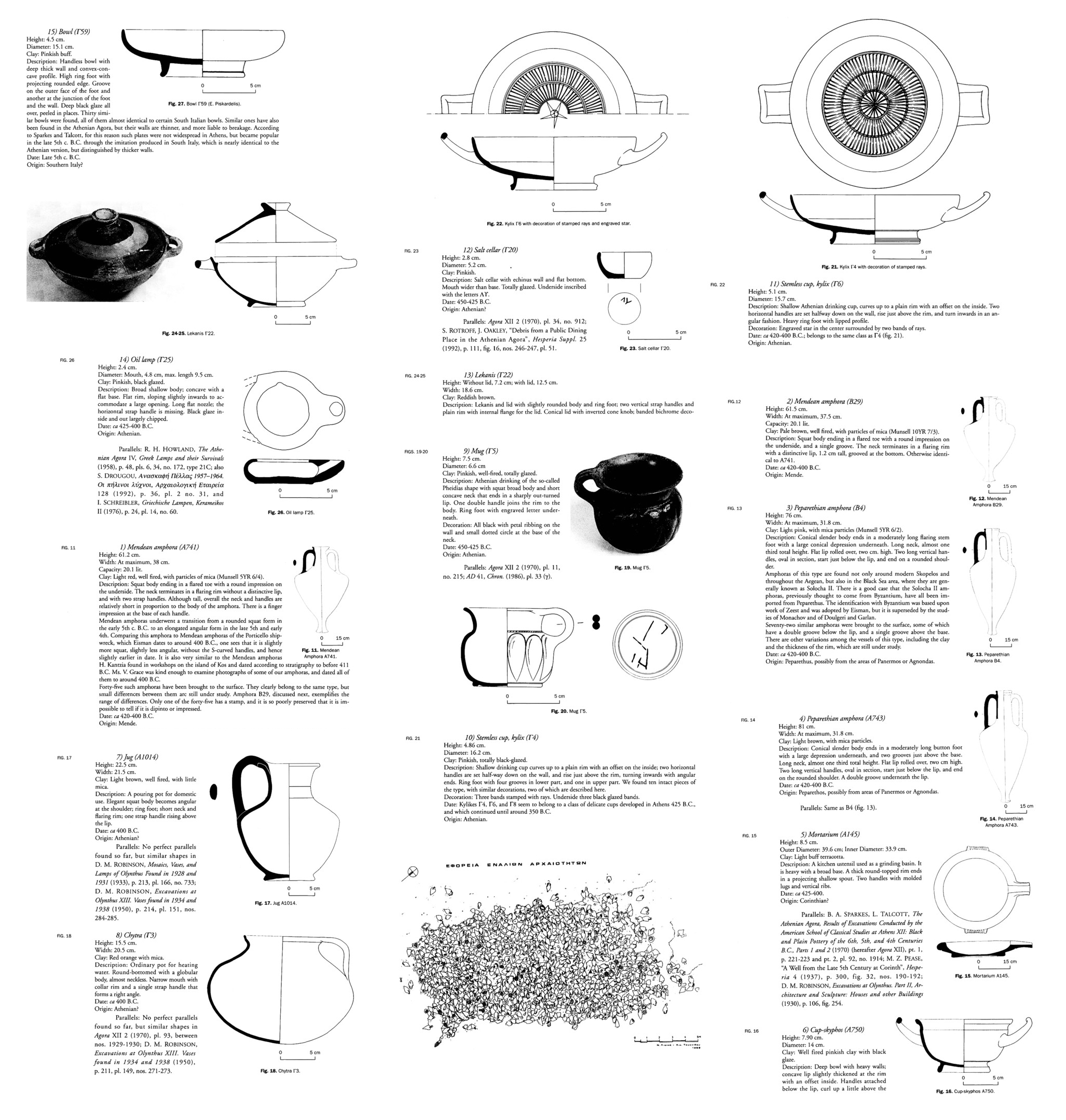

Taxes were extracted from subject polis, but not from Carthaginian citizens.[197] Significant revenues were extracted from import duties, and since Carthaginian ships controlled the Mediterranean trade west of Sicily, any goods flowing to Spain, North Africa or Sardinia had to be re-exported through Carthage.[198] Carthage imported significant quantities of Athenian pottery during the classical period.[199]

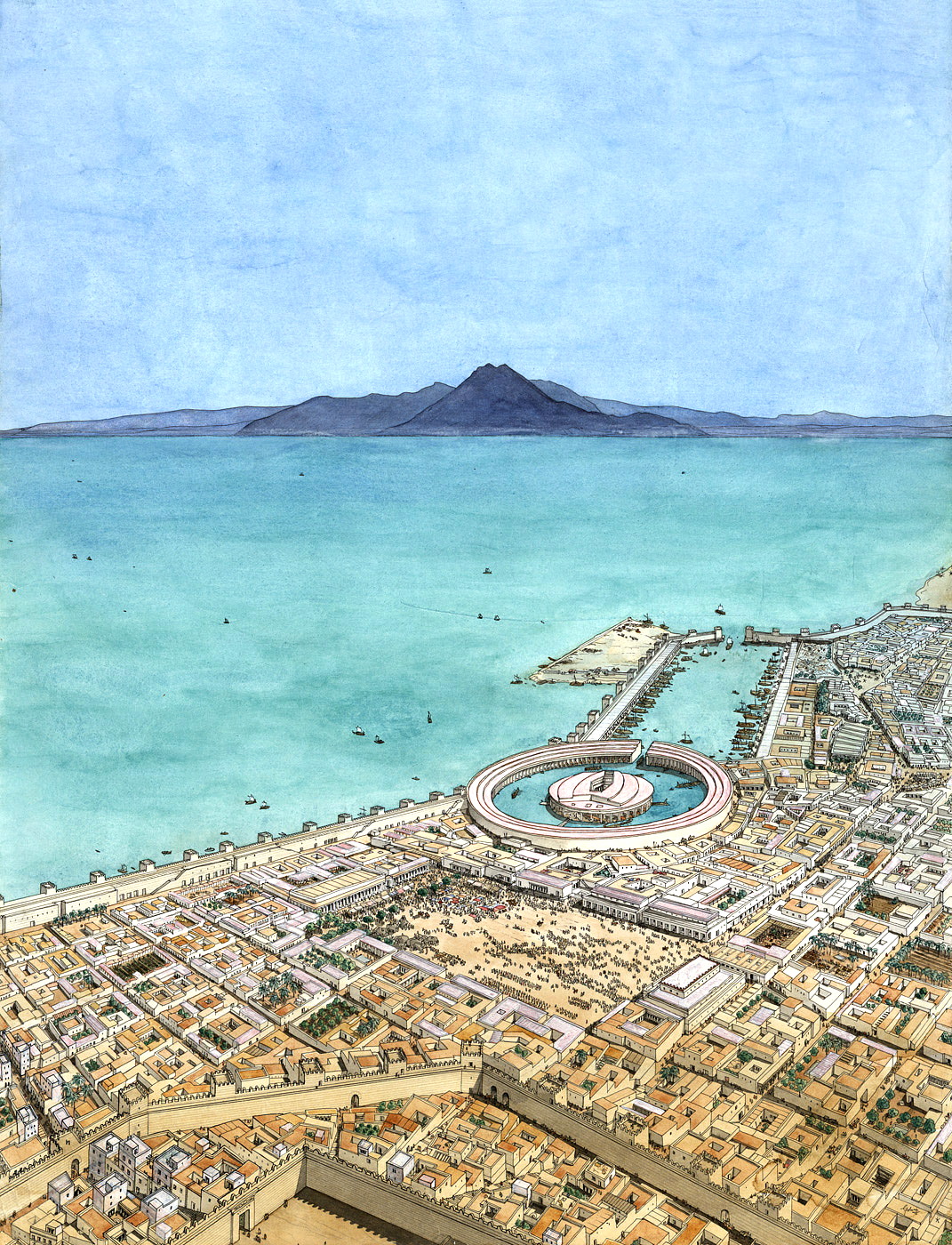

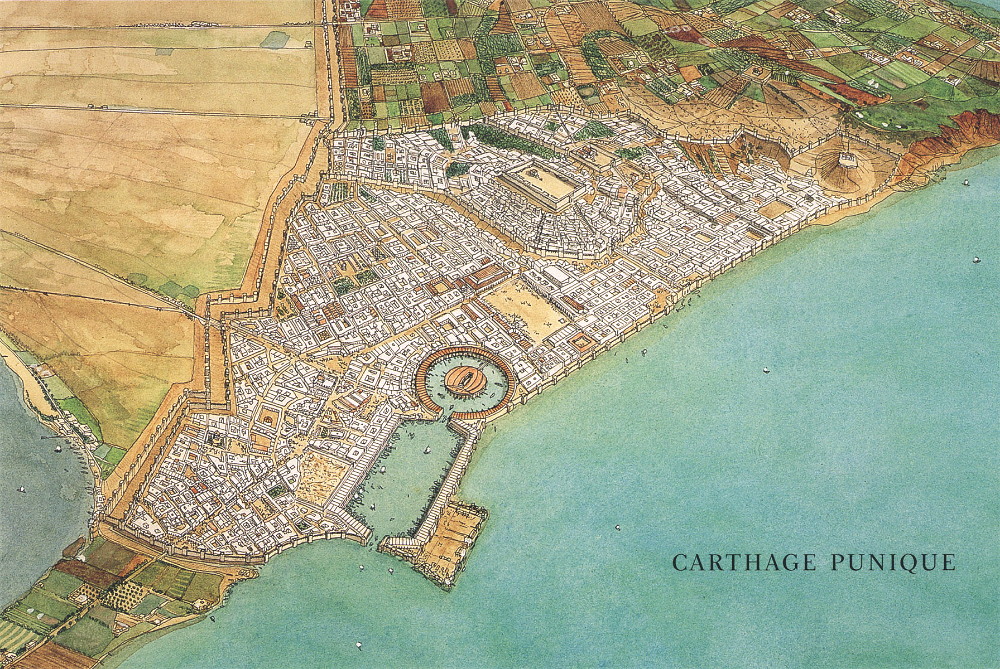

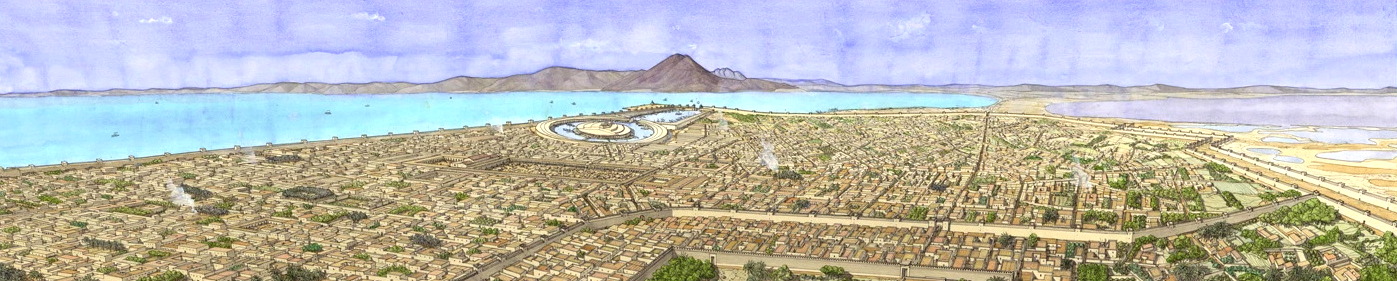

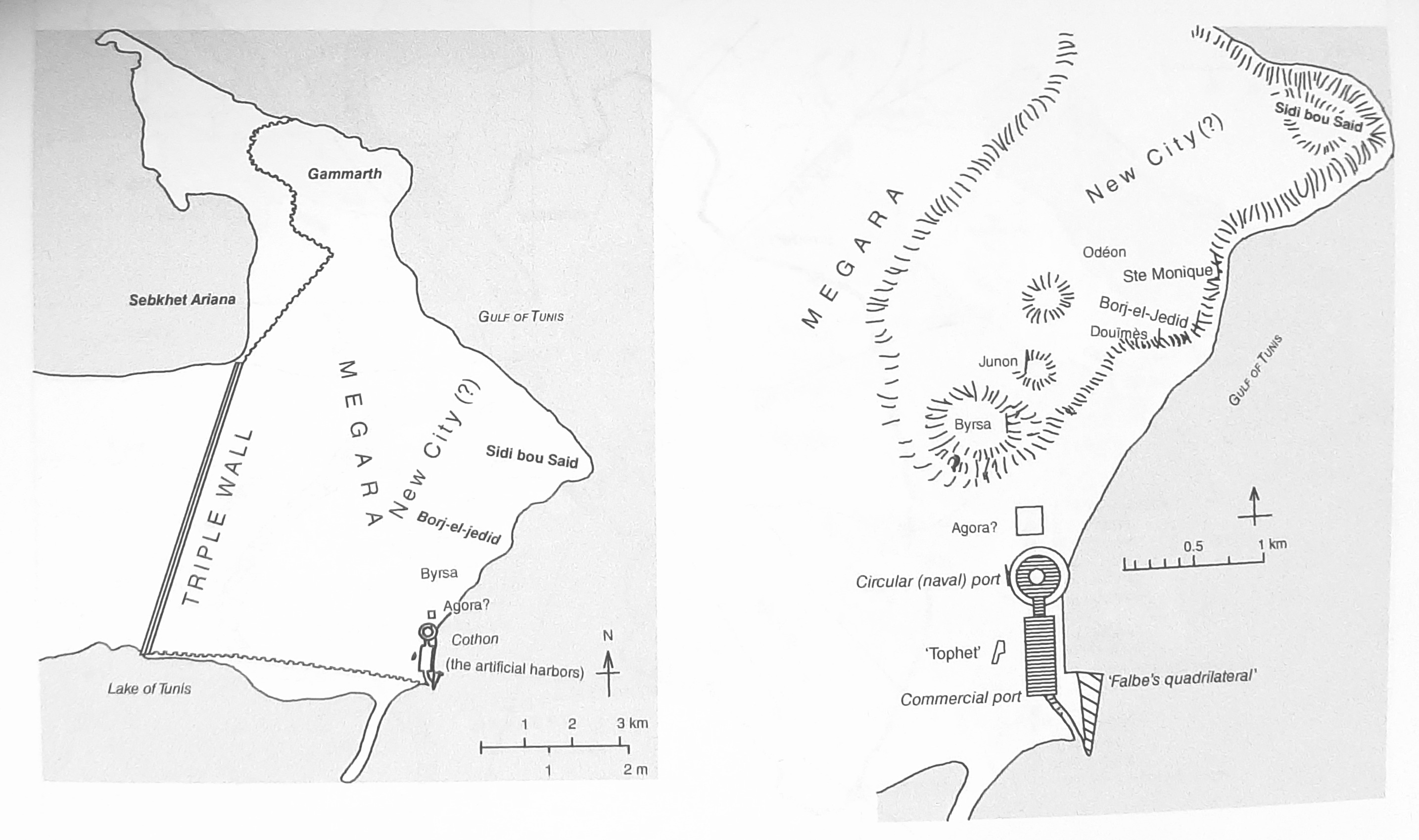

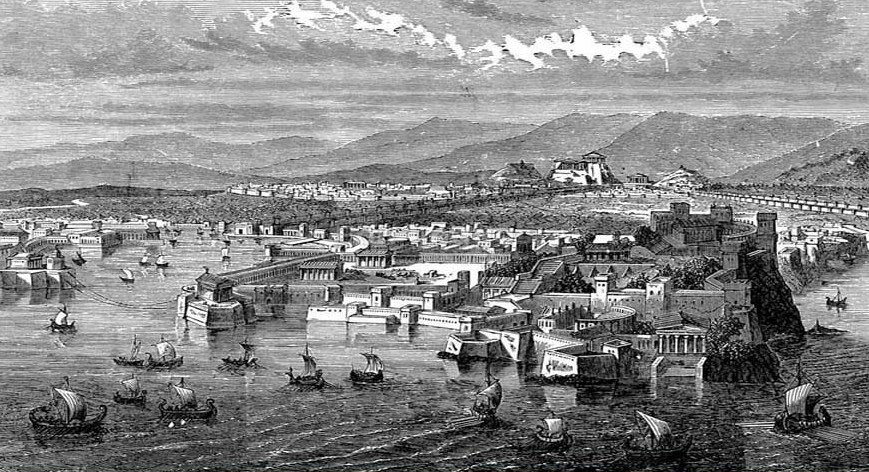

Jean-Claude Golvin’s views of Punic Carthage

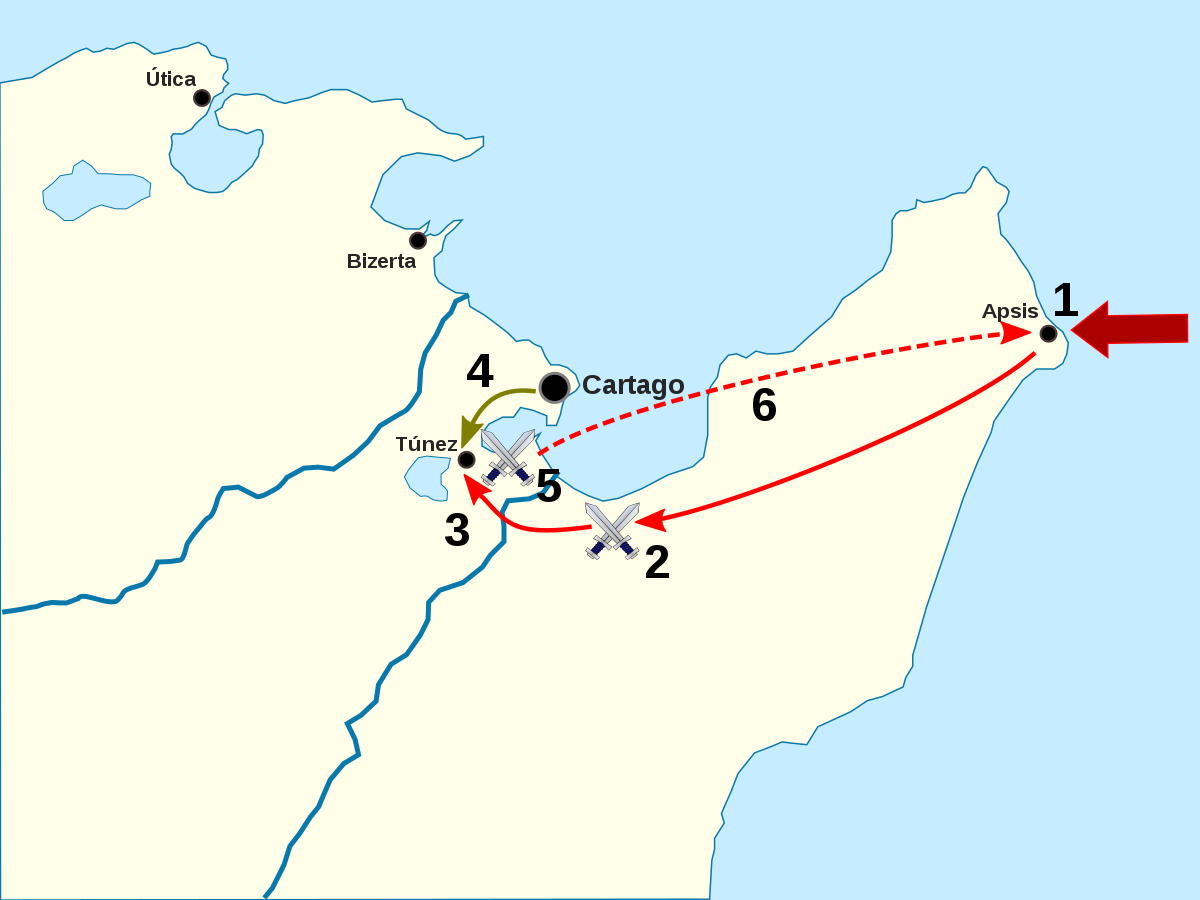

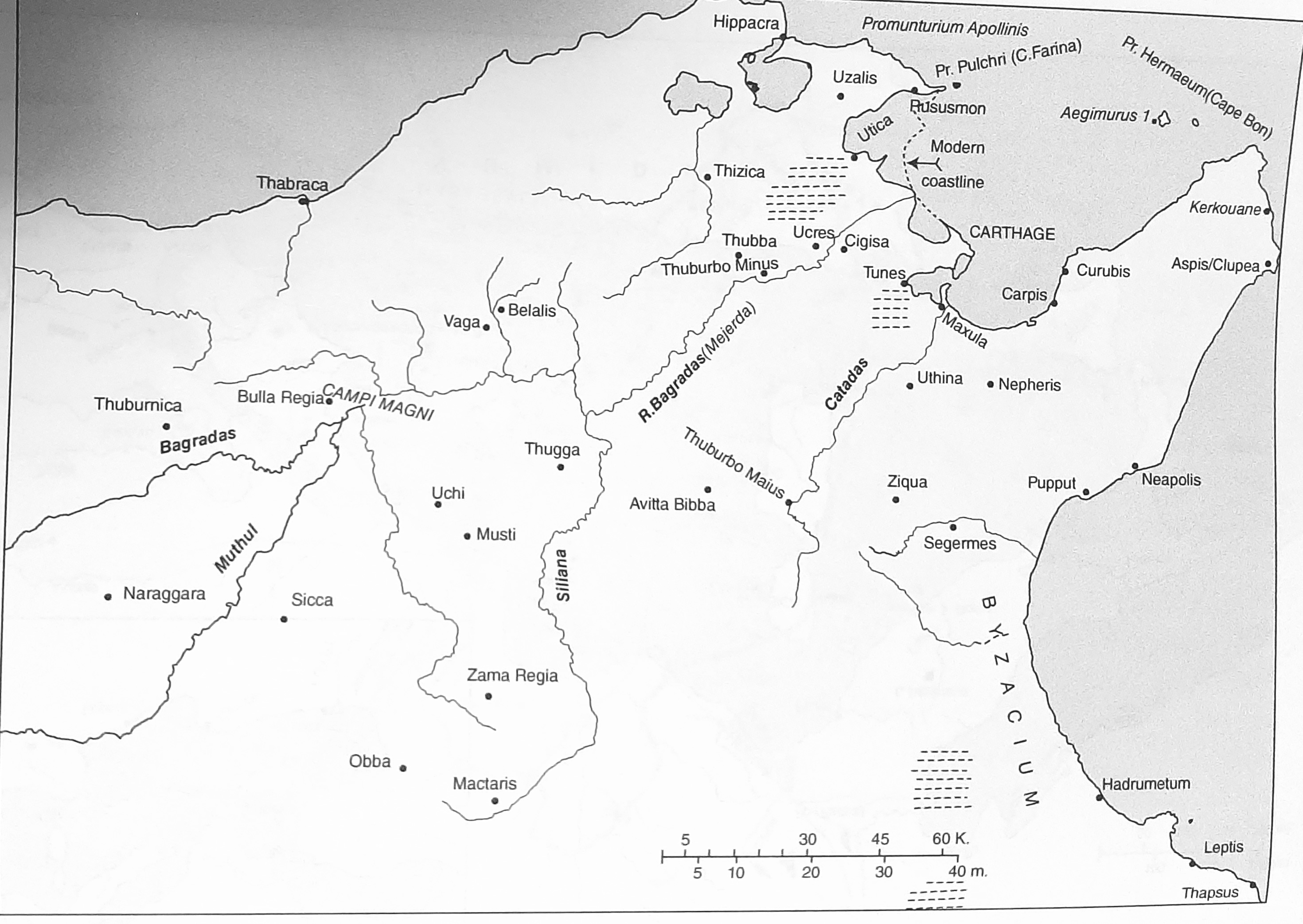

Carthage c. 264, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008)

Carthage itself produced gold coinage, sourced from African supplies, beginning in 350 BC, and maintained a mint in Sicily to produce silver coins so as to allow exchange with Syracusan and Greek currencies,[200] and another mint in Sardinia to produce silver and bronze coins.[201] Sardinian trade with Carthage included Sardinian amphora made to transport wine, olive oil, meat, fish, and salt.[202] Sardinia was also significantly a vital supplier of grain to Carthage, as was North Africa more generally.[203] Olive oil from Acragas (Agrigentum, modern Agrigento) was exported from Sicily to Carthage.[204] All these factors demonstrate the importance of the Carthaginian trade network for both profit and supply, significant necessitating control of the western Mediterranean.

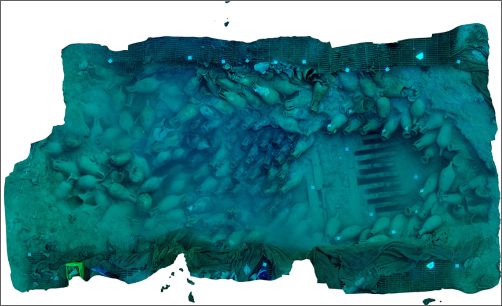

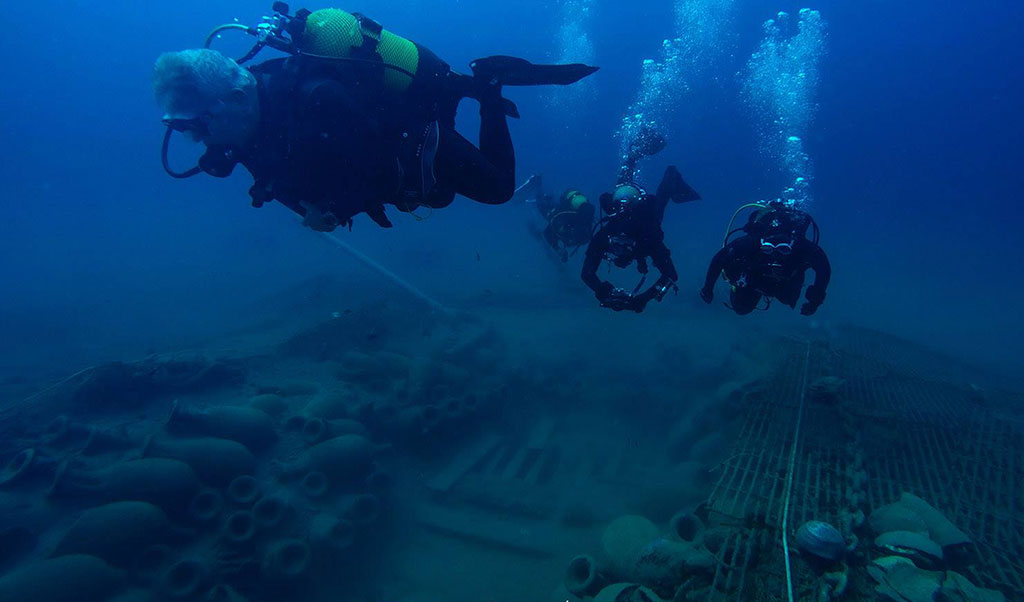

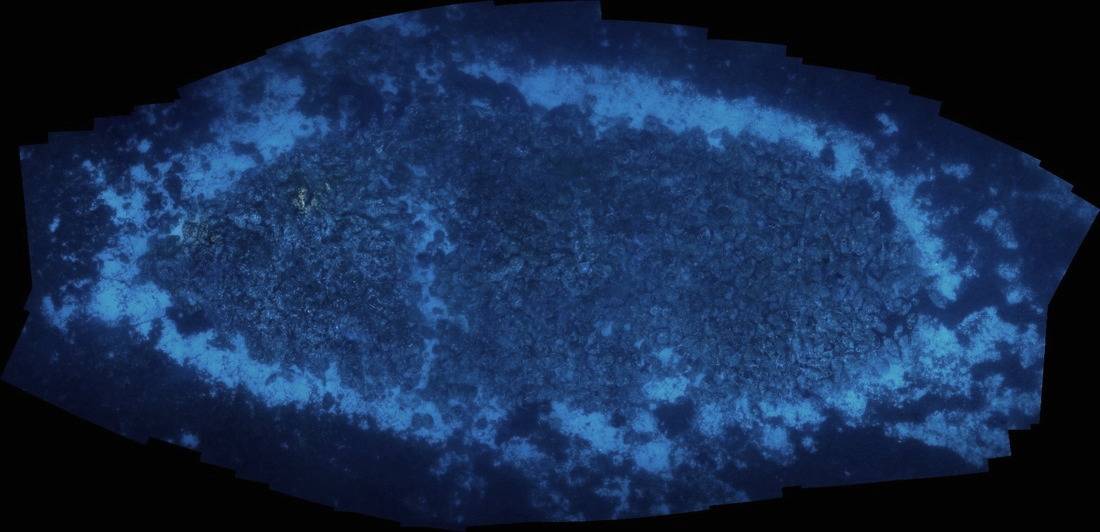

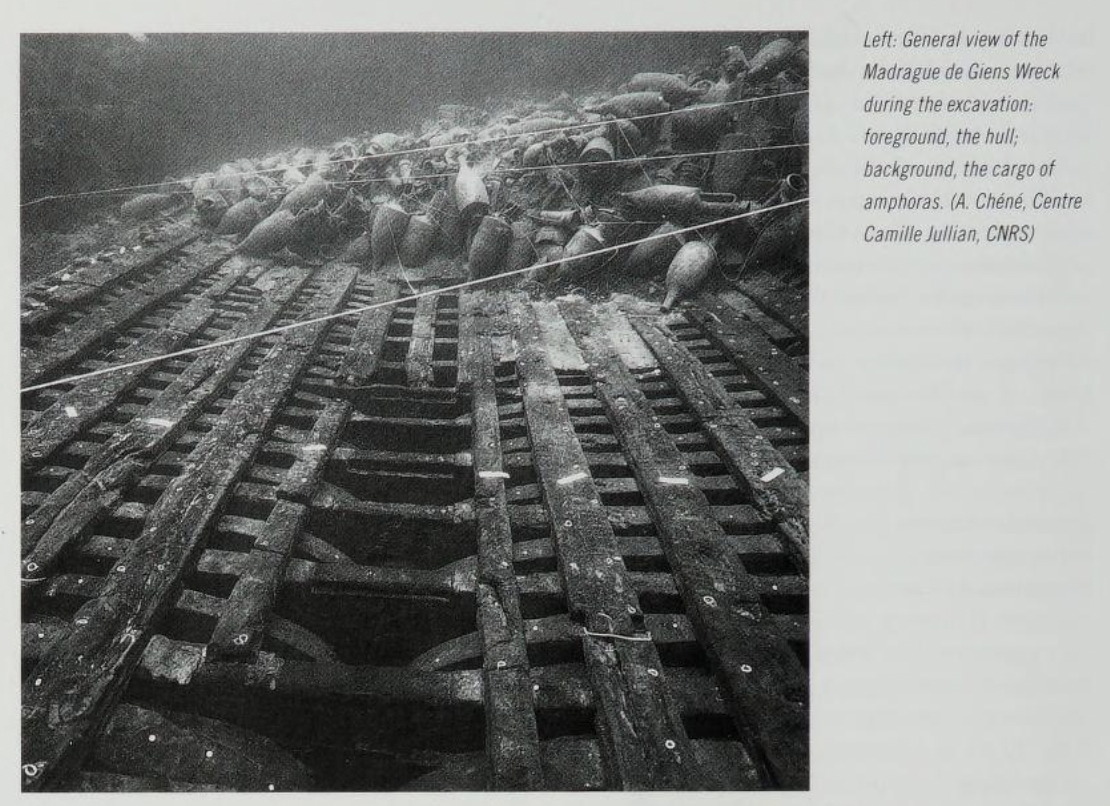

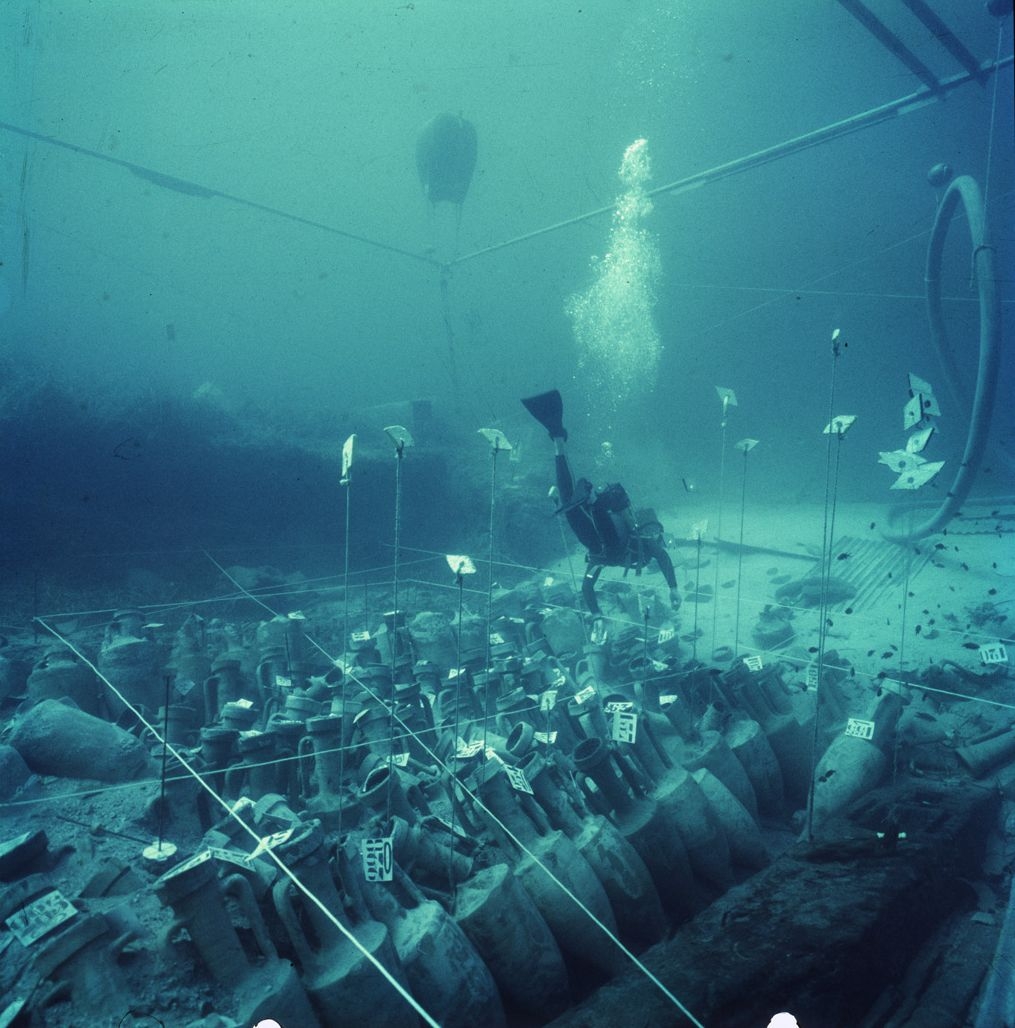

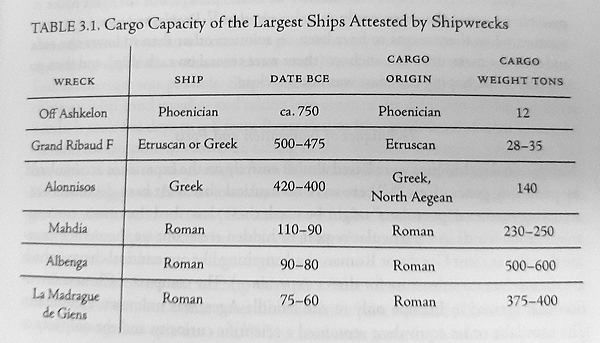

Bou Ferrer wreck, 30 meters long at 230 tons, containing 2,500 amphora, wrecked off the coast of Alicante, Spain in the mid-1st century AD.

Roman shipwreck carrying wine amphora, off the coast of Palermo (Panormus), Sicily, c. 2nd century BCE.

Amphora from the Grand Congloue wreck, 2nd century BCE., 150 tons, carrying 3,000 amphora.

Chiessi Wreck, Elba, c. 70-80 AD, carrying 7,000 amphora.

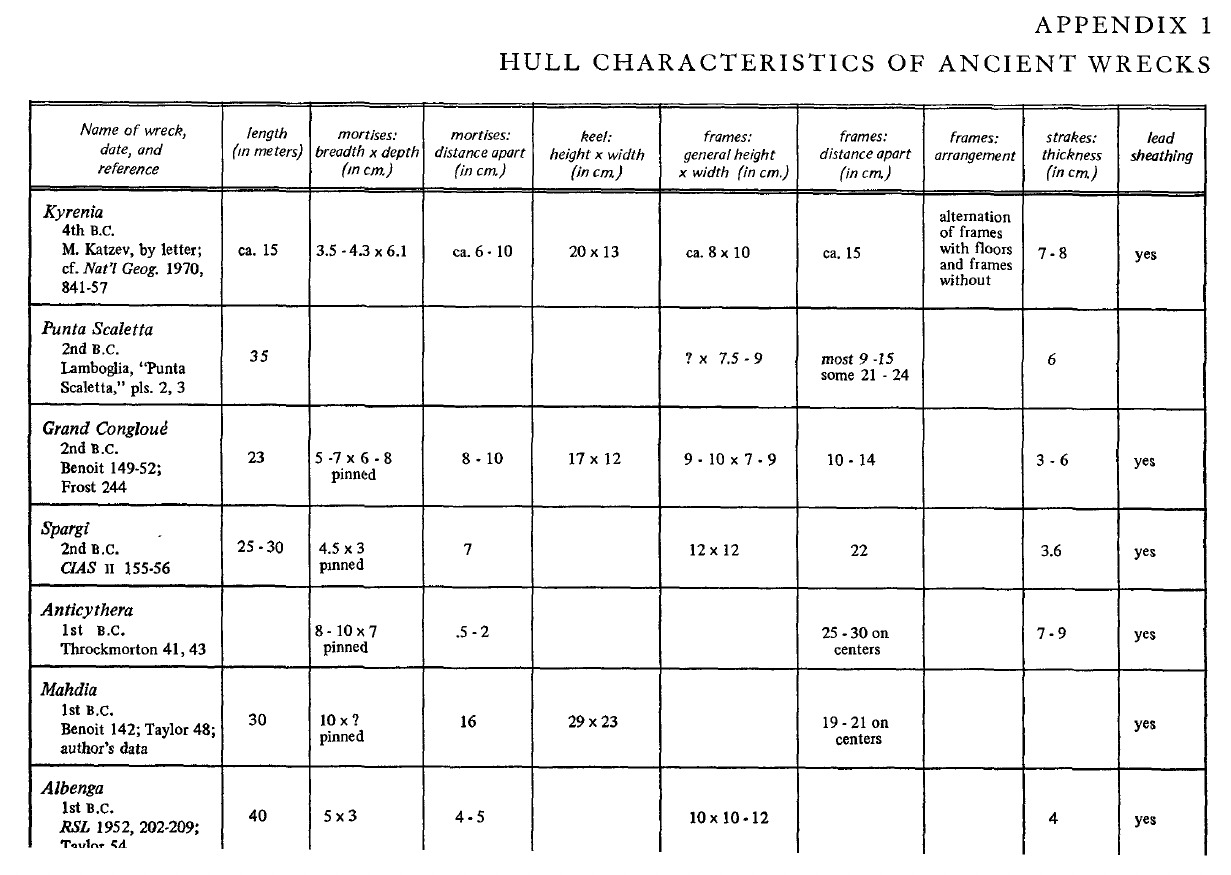

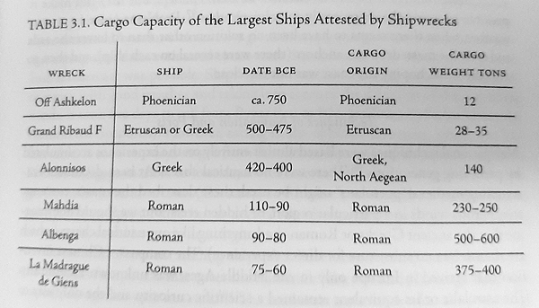

Hull characteristics of Greek and Roman ships, 5th to 1st century BC. Casson, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, p. 214

Sicily and the Treaty System

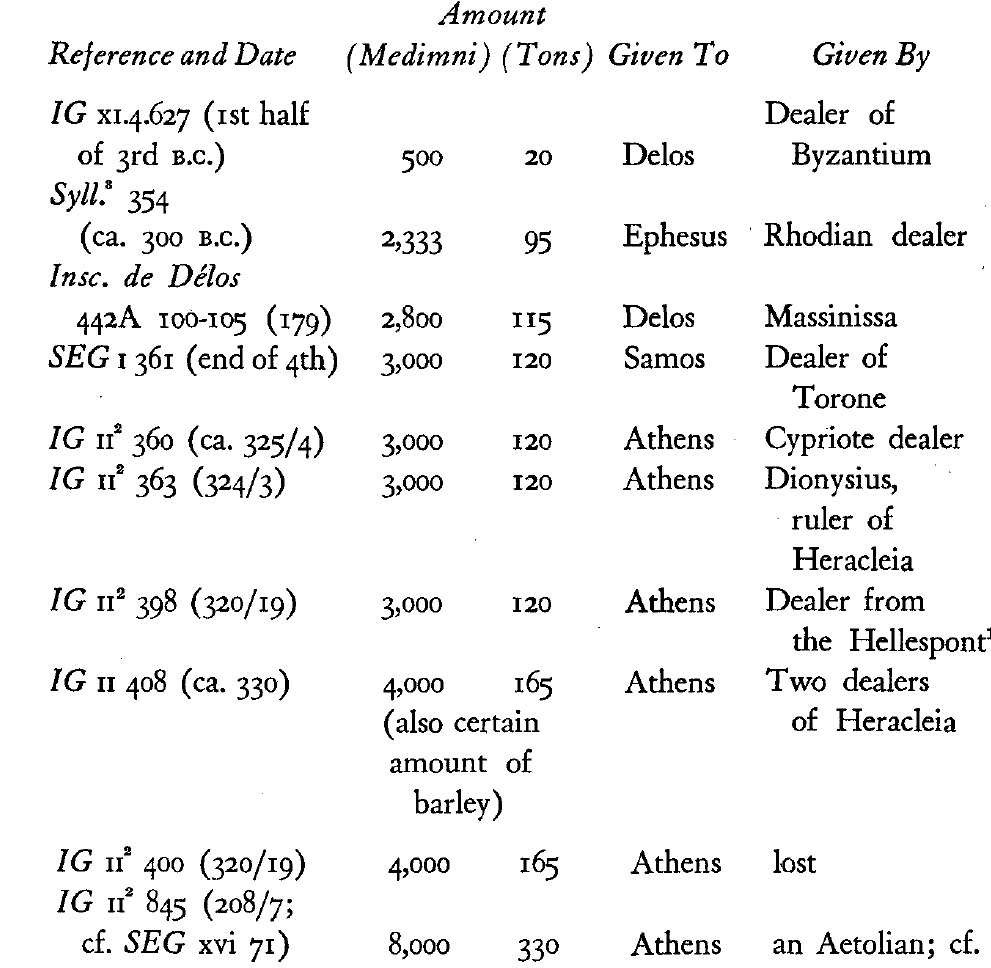

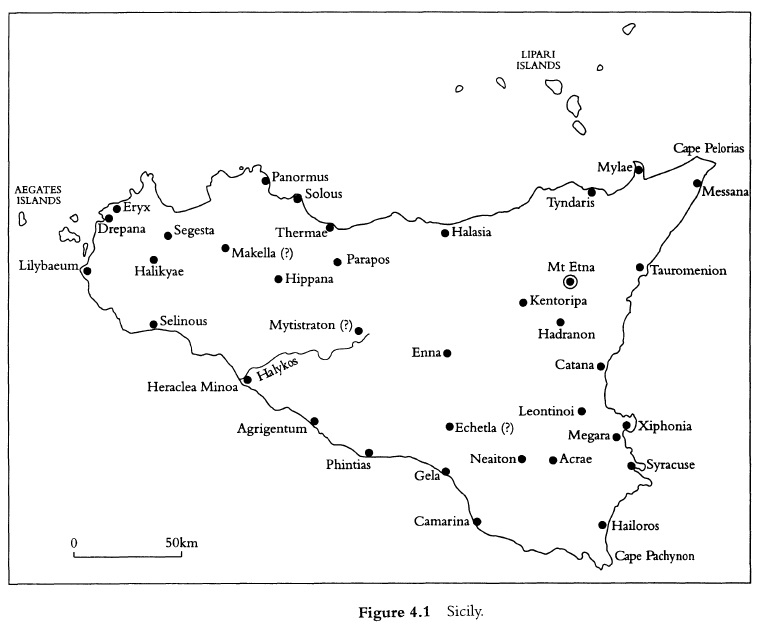

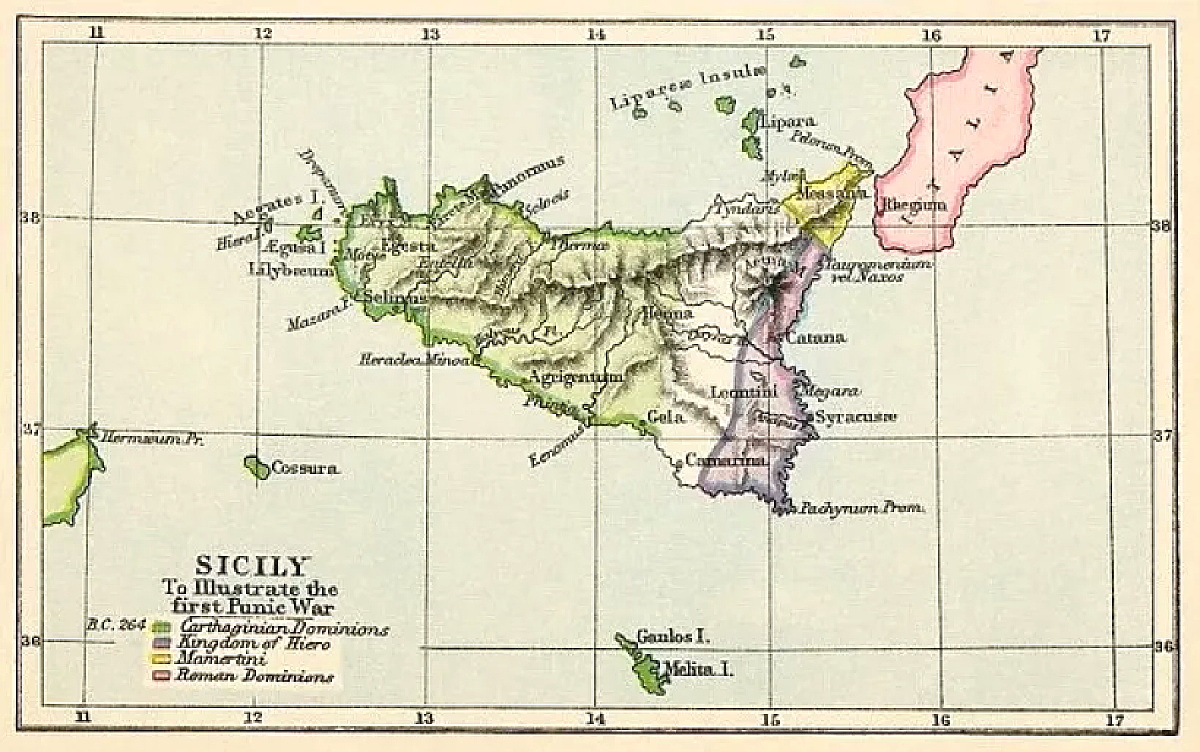

The First Punic War was fought over control of Sicily, and Messana was the flashpoint that brought the conflict to a head. As a crossroads of empires, Sicily was frequently divided and conquered, the island principally split between Phoenician (that is, Carthaginian) control in the west and Syracusan dominance in east. Syracuse was one of the wealthiest polis of the Classical and Hellenistic periods, and Sicily generally was a wealthy and significant producer of grain and artisanal goods which were exported across the Mediterranean.[205] Certainly the Carthaginians had good reason to be there, having inherited Phoenician colonies that had been established in the Bronze Age, but Roman interests after the war with Pyrrhus were gravitating towards Sicily.

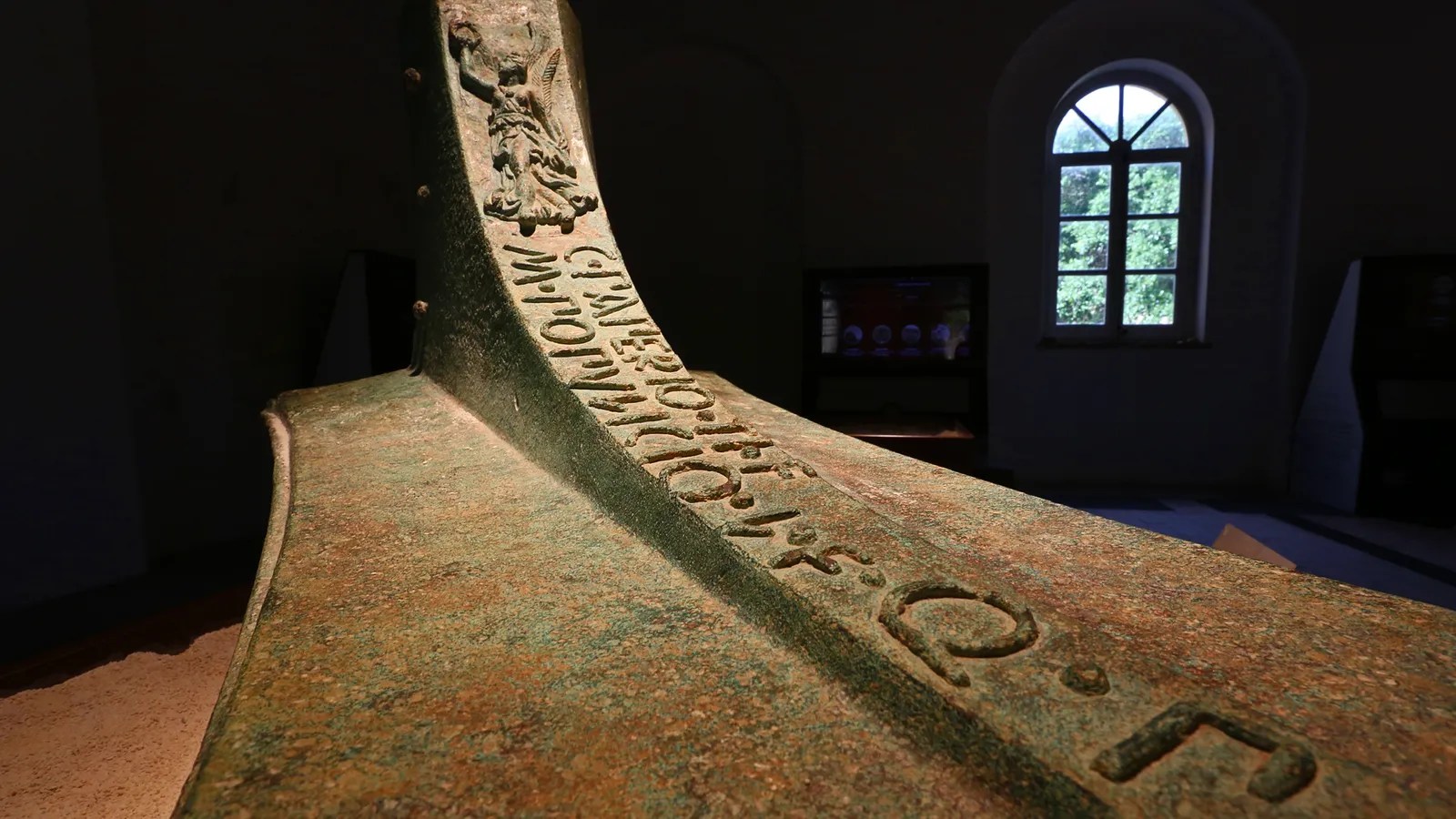

Indeed, the tragic nature of the conflict is demonstrated by the long-standing diplomatic and treaty basis of the Rome-Carthage relationship, reflected in a series of engravings on bronze tablets and housed in the treasury of the aediles beside the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in Rome.[206] The first such treaty was supposed to have dated to the late 6th century, or a few years after the expulsion of Tarquin, c. 507-5.[207] This initial treaty established the maritime and commerce regulations for territory controlled by each city-state and their allies.[208]

As Scullard points out the treaty was, from the Carthaginian perspective, primarily a trade treaty, focusing on the legality of trade in Sicily, Sardinia, and Libya, and essentially excluding Rome from any trade west of Cape Bon, although Roman citizens could still trade in Sicily and the Phoenician colonies.[209] Indeed, there was a steady flow of goods between Italy and Carthage itself,[210] notably exports of Carthaginian salt.[211] Much as the wealth of Syracuse drew the Athenian expedition of 415, the Carthaginians had considerable interest in controlling the Sicilian grain supply.[212]

Italy, 250 BC from Nathan Rosenstein, Rome and the Mediterranean, 290 to 146 BC (2012)

The second treaty, perhaps secured in 348 as reported by Diodorus and Livy,[213] was arranged when Carthaginian envoys arrived in Rome to secure “friendship and alliance,”[214] and reaffirmed Roman supremacy over its various allies in Italy, again recognizing Carthaginian interests elsewhere, including in Sicily, Sardinia and Libya. This second treaty deepened the peaceful respect of mutual boundaries between Rome and Carthage, and was described by Scullard as a treaty, “to refrain from mutual injury.”[215] This treaty was renewed in 306 and again in 279/8 when the Romans ostensibly supported the Carthaginians against Pyrrhus (see below).[216]

By the mid-3rd century, however, the Romans were beginning to encroach on Carthaginian trade. Rome’s Mediterranean trade influence was expanding after the recapture of Rhegium, with merchants from Ostia and then Neapolis bringing goods to Rome and exporting Roman wares – ironically something the Carthaginians had helped cultivate through their extensive trade networks, suppression of piracy, and treaties with Rome.[217] A pair of quaestores classici were created in 267 for administrative purposes, but also possibly to manage the growing Roman merchant marine, if not its small navy.[218] For the Roman city-state, collectively the treaty framework assured Rome that Carthage would not interfere in the territorial integrity of Italy and Rome’s various alliances.[219]

4th and 3rd century Roman wars before the Punic War, from The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic, ed., Harriet Flower (2014)

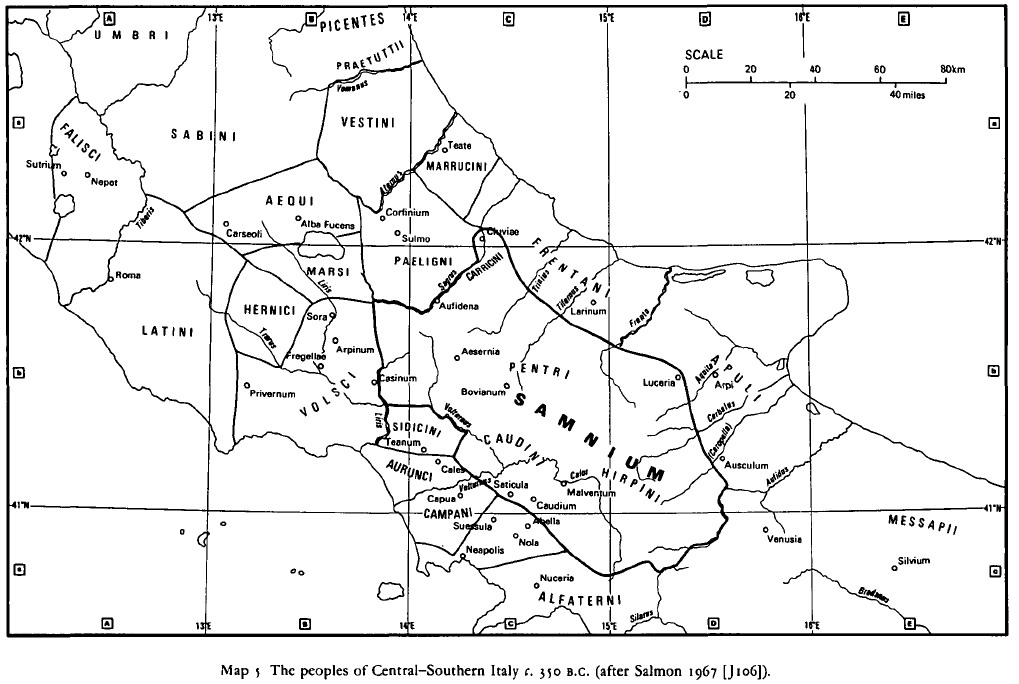

Central Italy c. 350 BC, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008)

Rome undoubtably had an interest in reducing piracy and controlling its coastal trade with the Italian cities.[220] Indeed, Rome had been leader of the Ferentina, the Latin League, which included the rest of Latium not already under direct Roman rule. Although the League itself had been dissolved in 338 with the conclusion of the Latin Wars and the beginning of the conflict with the Samnites of southern Italy, the Roman system of fides made it Rome’s responsibility to protect the cities and coasts under its dominion.[221] A festival in honour of the League, known as the feriae Latinae and held at the Alban Mount (Mons Albanus) variably from March to June, was celebrated every year, which the consuls and other magistrates were required to attend before departing for their appointments.[222]

It is to that time before Rome had conquered Italy, when Carthage and Syracuse were the major cities of the western Mediterranean, to which we must now turn to understand how the Romans came to war with Carthage in Sicily in 264. The reader can rest assured that the relevance of these exhaustive Punic struggles with the tyrants of Syracuse on countless Sicilian battlefields will become obvious when the Romans finally intervene.

Round Zero: Gelon, Dionysius, Dion and Timoleon, 483-337

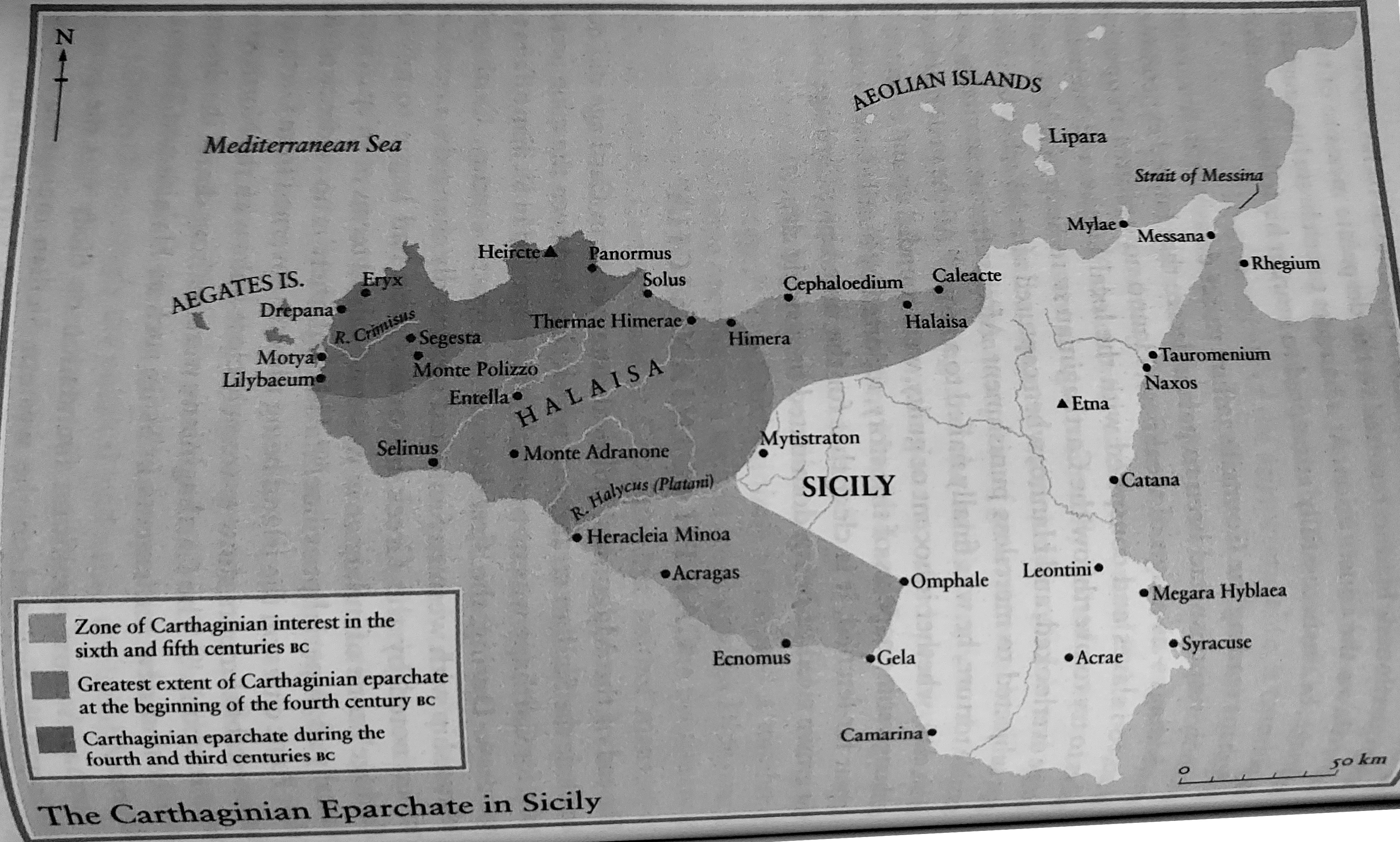

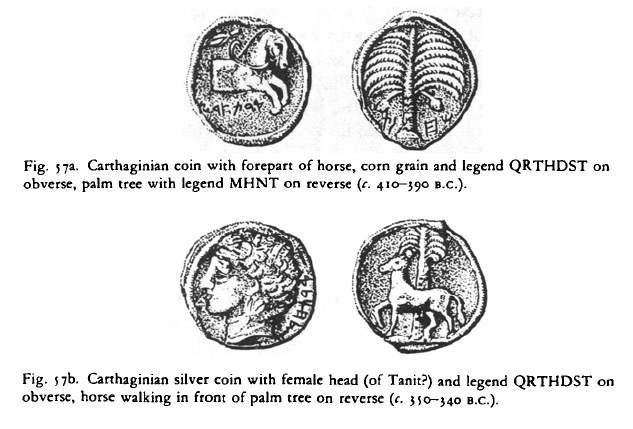

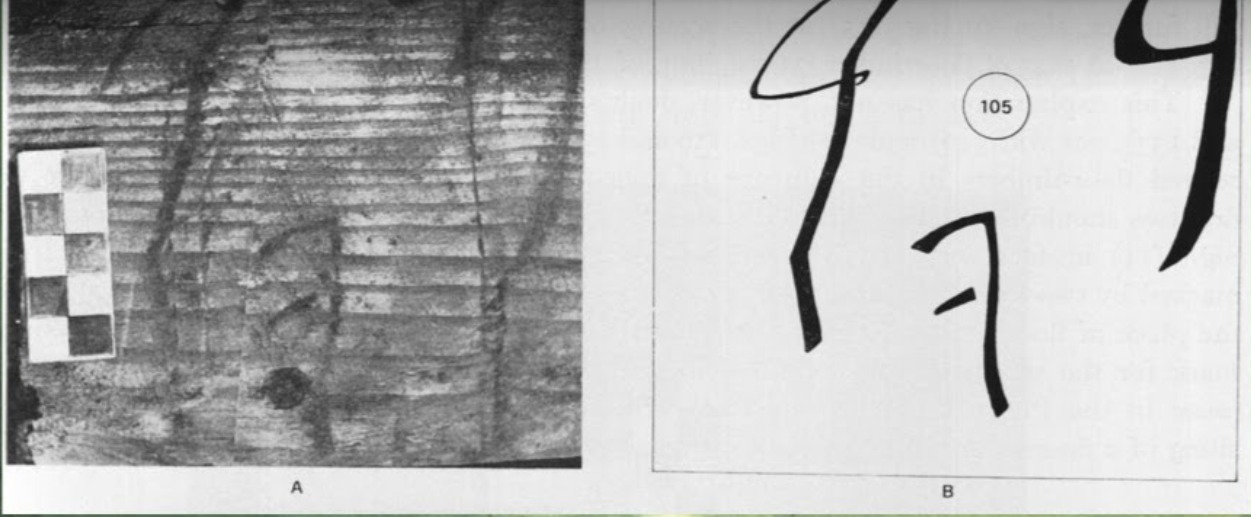

Phoenician settlers first arrived in Sicily in the 11th century, establishing settlements in the west. In the late 8th century they founded Panormus (Palermo), which became their capital in Sicily. The Phoenician and Carthaginian cities in western Sicily began minting their own coins in the late 6th century for paying mercenaries, the coins being marked by the Carthaginian military administration (qrthdst/mhnt).[223] Carthaginian and Punic settlers started arriving in Sardinia and Ibiza during the 5th century, pushing out the local Nuragi tribes. Sardinian amphorae for wine, olive oil, grain, salted meat and fish, and salt itself, were increasingly exported to Carthage, along with fine wears and luxury goods.[224]

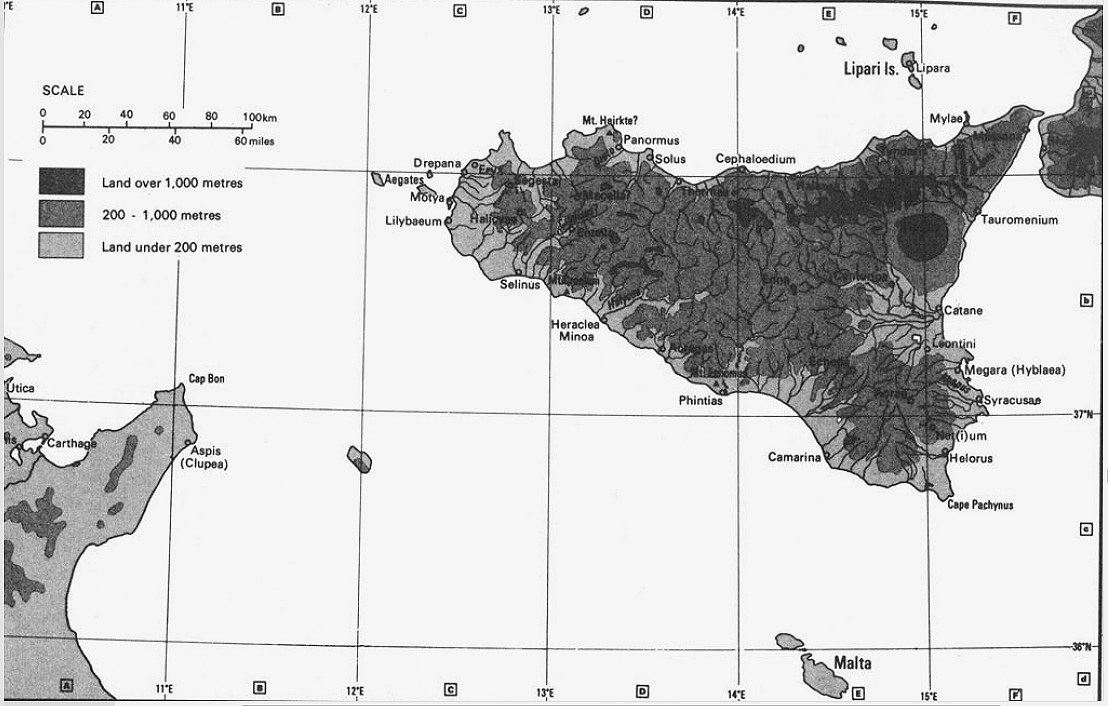

Southern Italy & Sicily in the Third Century BC, from The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2 (2008)

Carthaginian Eparchate in Sicily, from Richard Miles, Carthage Must Be Destroyed (2010)

Colonization of Sicily by Phoenicians, Rhodes, Corinth, Megara, and the Chalcidians.

Since the histories of Herodotus, the Carthaginians had been feuding with the Sicilian tyrants, foremost of whom was the tyrant of Syracuse. In 483 BC this was Gelon son of Deinomenes. His brother, Theron of Acragas, had captured and expelled Terillos, the ruler of Himera – an important polis east of Panormus.[225] Terillos appealed to his guest-friend Hamilcar, son of Hanno and a Syracusan mother, and the grandson of Mago the Magonid.[226] In 480 Hamilcar, allied with the forces of Anaxilas, tyrant of Rhegium – that city together with Messana respectively being the Italian and Sicilian crossing-points for the Straits – brought over to Panormus an army of Libyan, Spanish, Sicilian, Sardinian and Corsican mercenaries, and then marched directly on Himera.[227] Gelon and Theron confronted Hamilcar with the Syracusan army, and in the ensuing day-long battle, supposedly fought on the same day the Athenians defeated Xerxes at Salamis (September 480), Hamilcar was killed (either in battle, or by assassination, or by suicide) and the Carthaginian force routed.[228] In the peace treaty that followed, the Carthaginians abandoned Himera to Gelon and paid an indemnity of 2,000 talents.[229] Gelon died in 478 and his brother and successor Theron and the Deinomenid dynasty continued the Syracusan supremacy in Sicily, and indeed no Carthaginian army entered Sicily for the next 70 years.[230]

Tetradrachm of Gelon I, c. 485-478

Battle of Himera, 480, by Giuseppe Sciuti in 1873

Syracuse as a seapower was temporarily supreme in the western Mediterranean, evidenced by the naval victory over the Etruscans at Cumae in 474.[231] Carthage’s merchant trade, nevertheless, was growing, shipping Spanish tuna to Greece and Greek commodities to Spain. One fifth of the amphorae flowing into Carthage originated from the Ionian islands, and Carthaginian merchants could by this time be found across Mediterranean ports.[232] Syracuse’s ally Acragas, a stronghold strategically positioned on the south-western Sicilian coast, halfway along the land route between Lilybaeum (Motya) and Catana (Catania), north of Syracuse,[233] became rich selling olives to Carthage.[234]

Syracusan seapower declined over the course of the 5th century as Carthage increasingly took control of the western Mediterranean trade. The Carthaginians took advantage of Syracuse’s relative weakness following the war Athens (415-13) to intervene in a dispute between Selinus, an ally of Syracuse, and Segesta, siding with the latter. In 410, Hannibal, the grandson of Hamilcar of Himera, marched 5,000 Libyan and 800 Campanian mercenaries to support Segesta, and with these defeated the army from Selinus in a pitched battle. Selinus turned to Syracuse for aid, and Hannibal marshalled his main army of Libyan levies, Iberian mercenaries, and siege engines. In the spring of 409 he brought them over from Carthage with a fleet of 60 ships and 1,500 transports.[235]

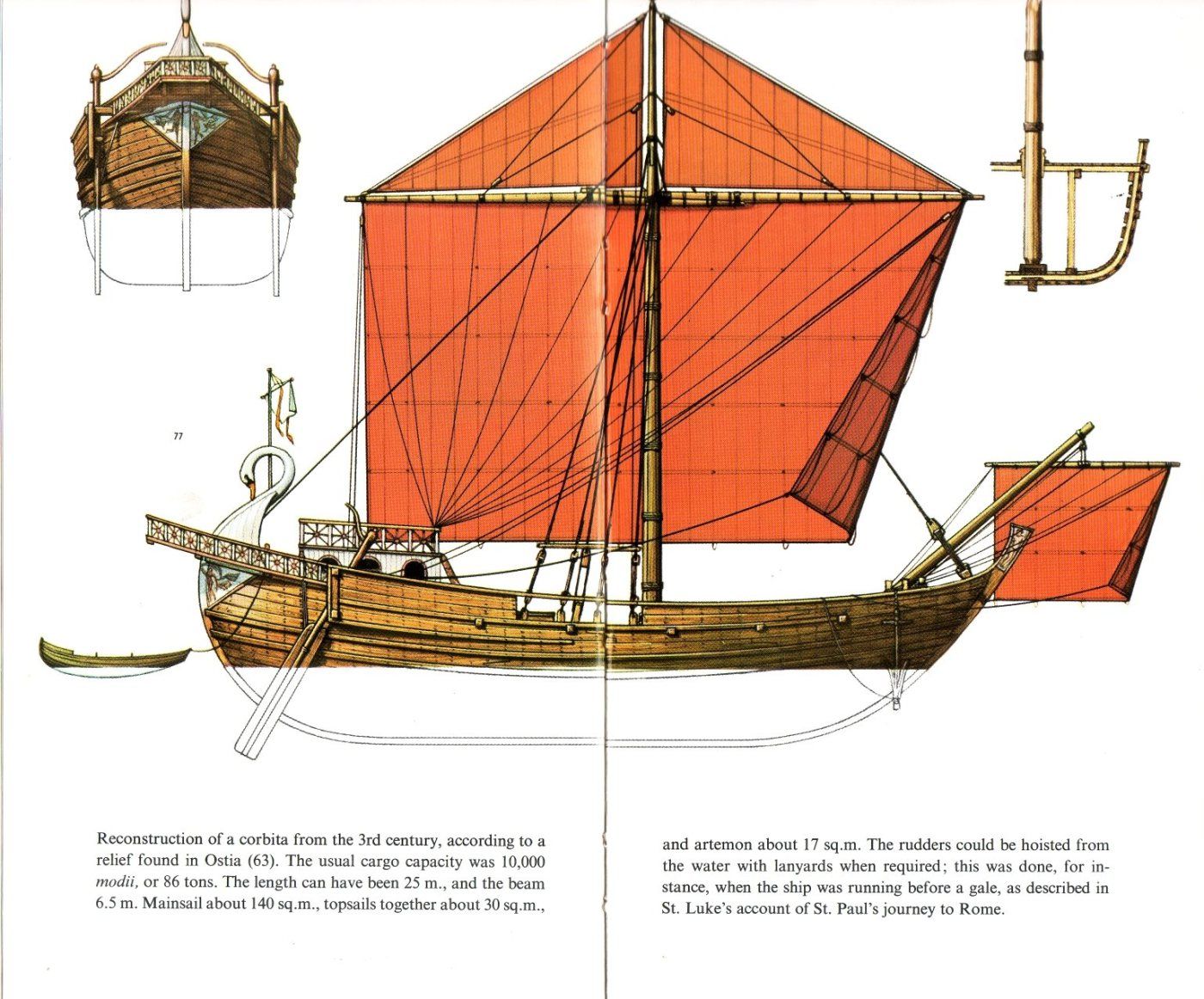

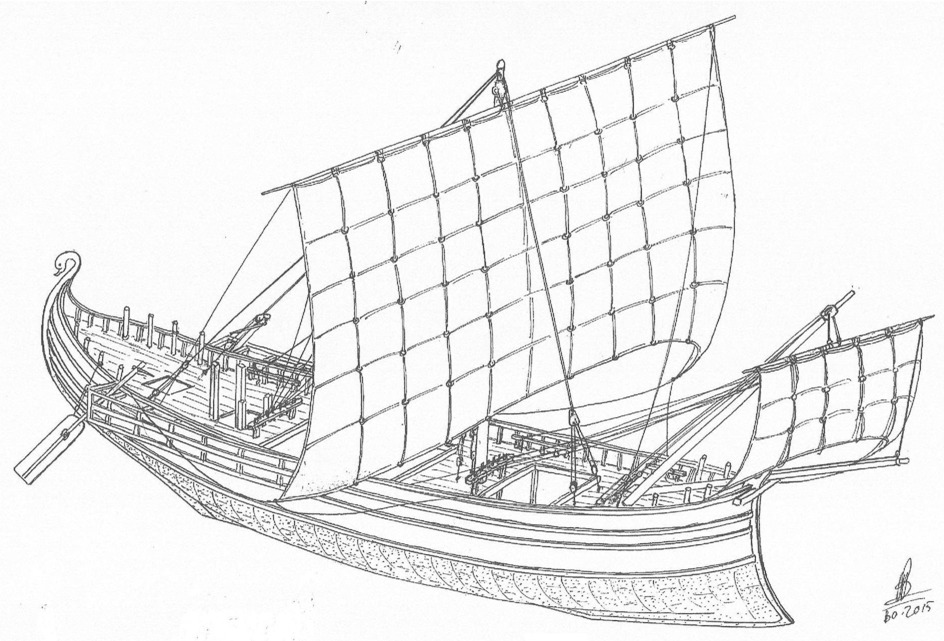

Roman corbita, 1st to 3rd century AD, 400 to 500 tons.

Albenga, Italy, wreck, 1st century BCE, 500 tons, carrying as many as 10,000 amphora

The Mahdia ship, Tunisia, carrying 70 marble columns , 1st century BCE

Landing at the old Phoenician colony of Motya (Mozia) Hannibal quickly assembled his total force, crossed the Mazarus River, and then besieged Selinus,[236] which he stormed in a nine day siege with the use of six huge siege towers and an equal number of battering rams, pillaging it and demolishing the walls. The Carthaginians slaughtered the 16,000 inhabitants and enslaved 5,000 more, with only 2,600 citizens from Selinus escaping to Acragas.[237] Hannibal ignored peace entreaties from Acragas, and advanced on Himera with 60,000 men, defeating the Himeran forces that desperately marched out to confront him.[238] The citizens were evacuated by Diocles of Syracuse with 25 triremes, leaving only a rearguard which, along with 3,000 leading citizens, were inevitably slaughtered when Hannibal captured the city three days later and utterly destroyed it, the siege and final assault having cost 6,000 of his soldiers.[239]

Syracuse had been engaged in a war against the Chalcidian colonies in Sicily, Naxos, Catana and Leontini,[240] and the Sicilians were too slow to despatch a more powerful relief force under Diocles to prevent to destruction of Himera.[241] Having avenged his grandfather in 480, and demonstrated Syracuse’s impotence to stop him, Hannibal paid off his army and returned to Carthage to great celebration.[242] Hermocrates of Syracuse achieved some success raiding the countryside around Panormus,[243] and in early 406 Syracuse sent ambassadors, but Carthage was intent on renewing the war.

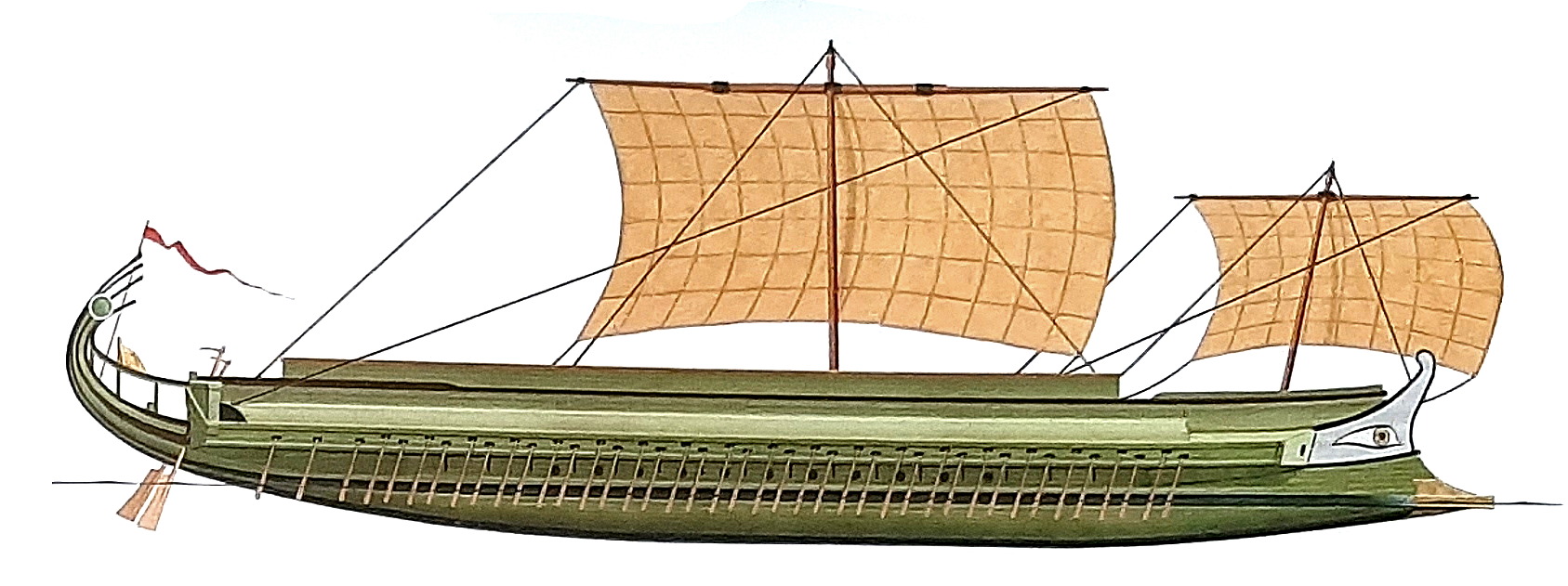

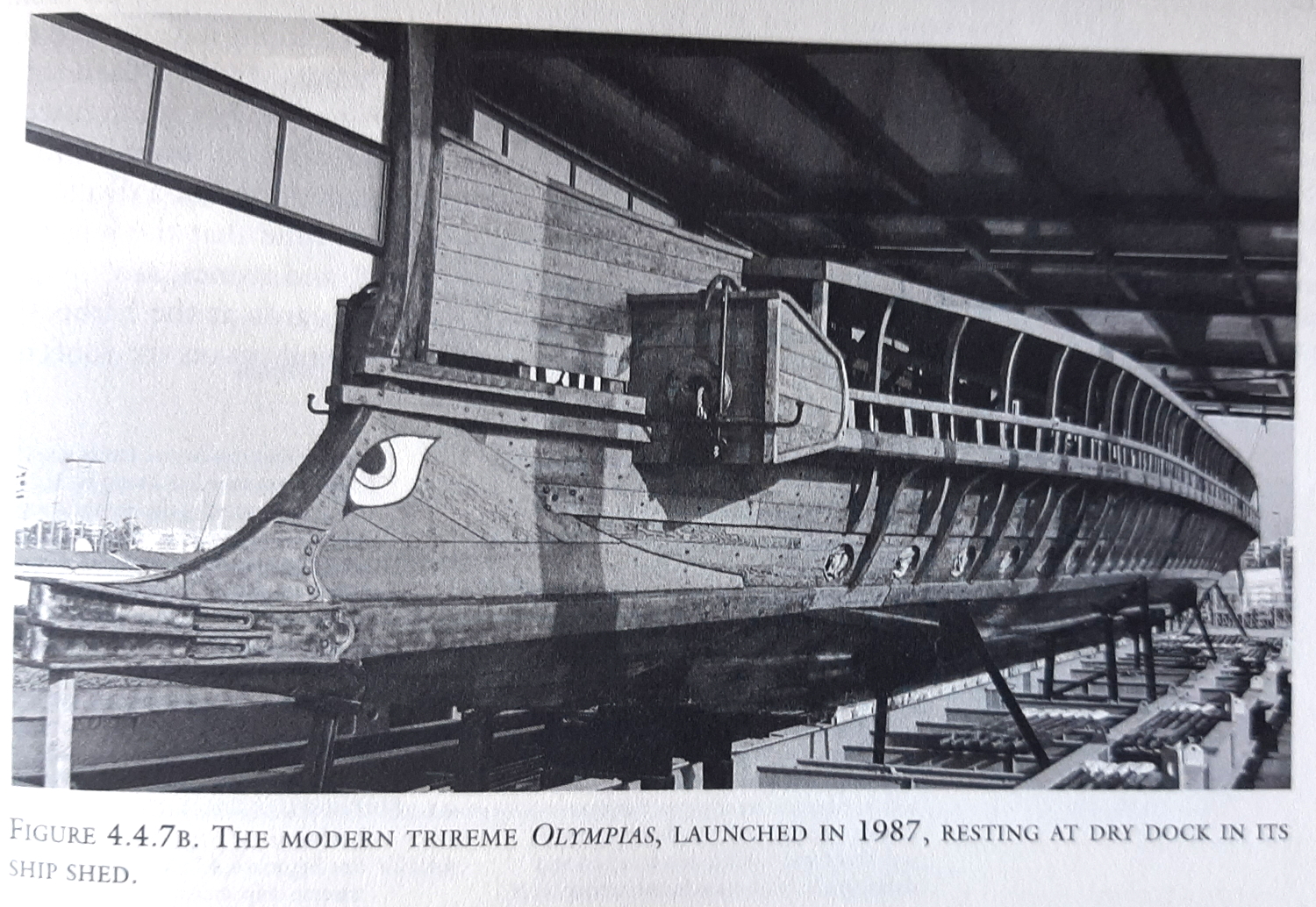

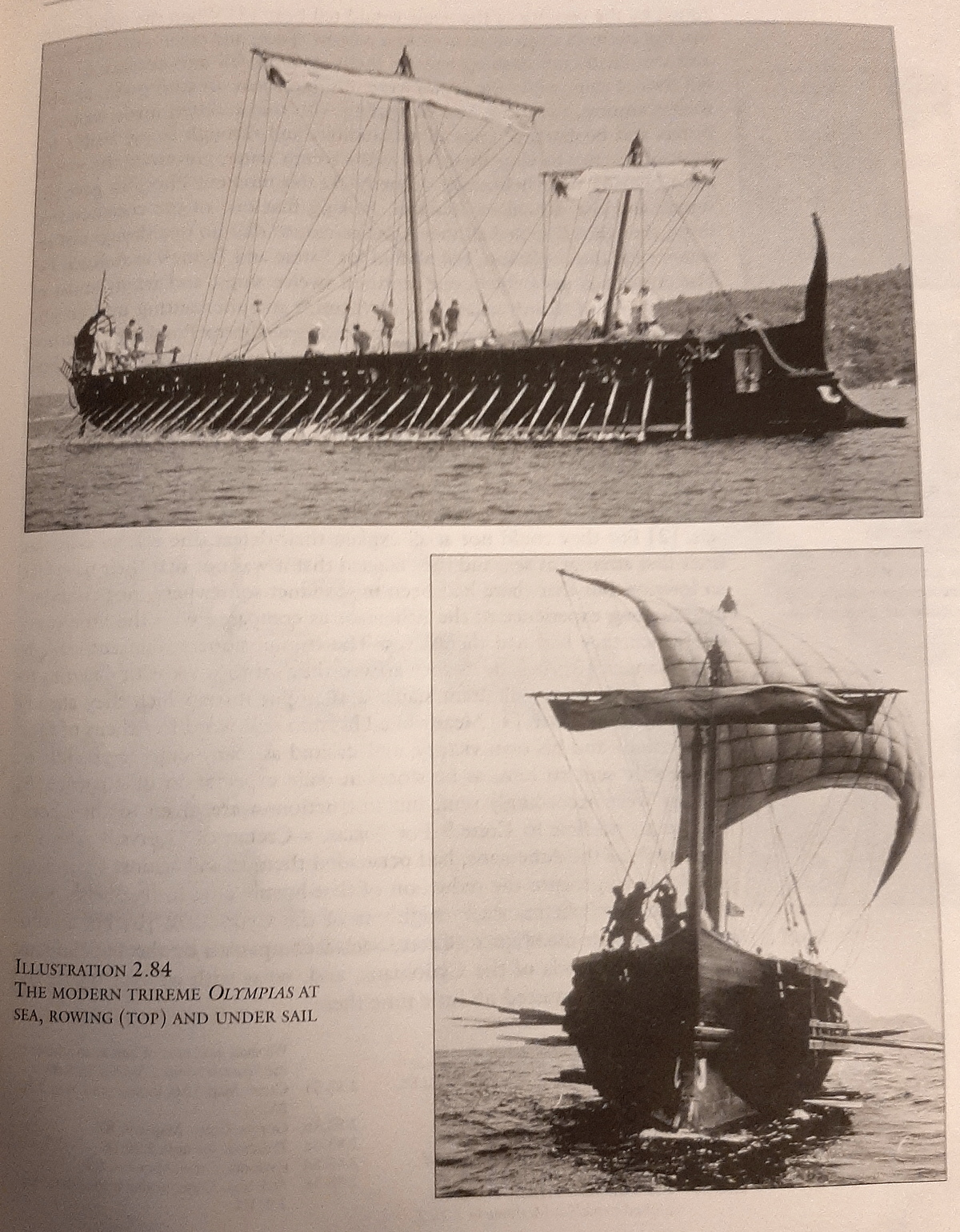

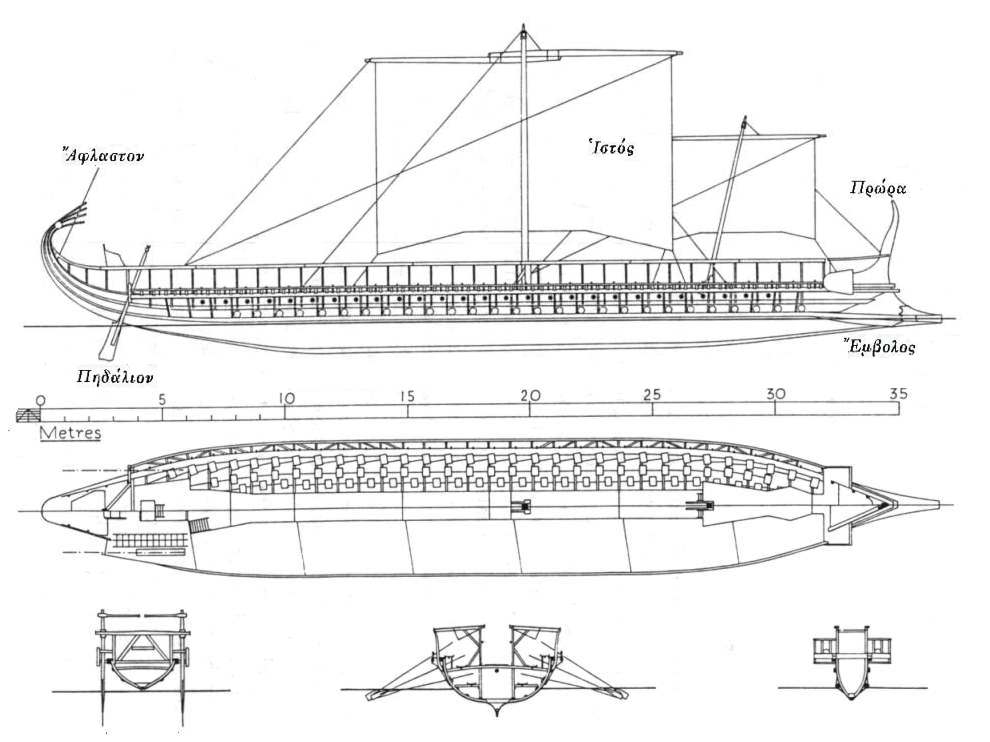

Illustration of a Carthaginian trireme. The recreation trireme Olympias is 37 meters in length and displaces 47 tons.

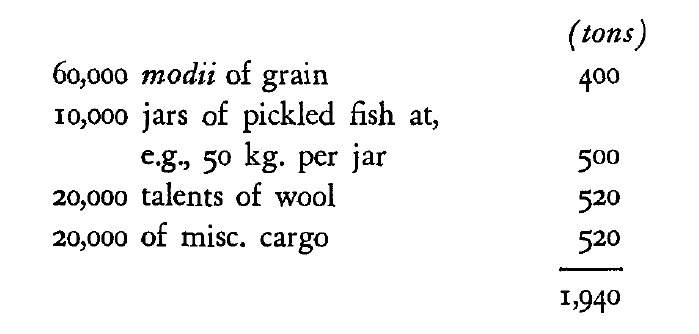

Hannibal and Himilco gathered their army at Carthage, but their advance squadron of 40 triremes was defeated off Eryx by a Syracusan force of similar size.[244] The main force under Hannibal nevertheless crossed over with 50 triremes, and during the spring laid siege to Acragas.[245] Hannibal, however, succumbed to a pestilence and the siege was delayed under Himilco.[246] The relief force from Syracuse commanded by Daphnaeus at last arrived with 30,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry and 30 triremes.[247] Himilco formed up to meet them with his entire army and was defeated, with 6,000 killed.[248] Daphnaeus occupied the Carthaginian’s camp, where he was joined by reinforcements from Acragas under Dexippus the Lacedaemonian, although the siege was not broken.[249] Indeed, Himilco expected he could outlast the Syracusans, and although they were raiding his supply lines, he retaliated by using 40 triremes to intercept a Syracusan grain convoy bound for Acragas, sinking eight of the escorts and capturing all the transports. He eventually also paid 15 talents to get Syracuse’s Campanian mercenaries to change sides.[250] In December 406, with provisions nearly exhausted, Daphnaeus evacuated Acragas by night, the refugees fleeing to Gela.[251] Himilco, after a siege that had lasted eight months, took the city at dawn and executed the survivors, ruthlessly sacking the rich Acragantine households.[252]

The campaign continued the following year, 405, but under different leadership at Syracuse: Dionysius son of Hermocratus, with money supplied by the wealthy Philistus, and hesitant support supplied by Dxeippus at Gela, was elected strategos autokrator and overthrew the democracy in Syracuse.[253] Surrounding himself with a 1,000 man bodyguard, he put Daphnaeus to death and consolidated his power.[254] Himilco, in the meantime, advanced to Gela and besieged it, prompting Dionysius to march there with 30,000 men, 4,000 cavalry supported by 50 warships.[255] After a brutal battle in which he failed to raise the siege, he withdrew back to Syracuse, the army falling apart along the way. Himilco took Gela, but difficulty executing a siege of Syracuse itself prevented him from following up this success, and late in 405 he negotiated peace with Syracuse. The Phoenician presence in the west was recognized by Dionysus, and tribute paid to Carthage by the defeated cities, the refugees from which were restored.[256]

Dionysius I of Syracuse (432-367), after Claude Vignon

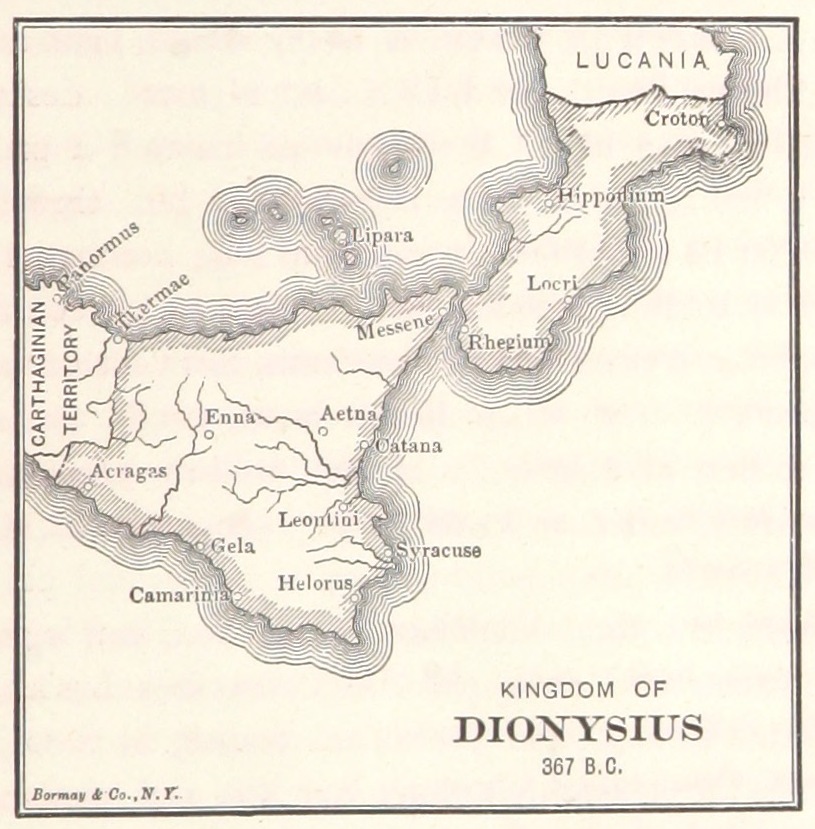

Kingdom of Dionysius I of Syracuse.

This peace was not destined to last, however, and in 397, Dionysius again declared war on the Carthaginians. He first expropriated and massacred the Punic civilians living within his realm, and then marched to take Motya on the western coast. With 80,000 men, 3,000 cavalry supported by about 200 triremes and 500 merchant ships, he laid siege to Motya and pillaged the countryside, besieging also Aegesta and Entella.[257] Himilco, still overlord in Sicily,[258] recognized another amateur mistake by Dionysus and thus with a raiding force of ten triremes burned the tyrant’s ships still in harbour at Syracuse. Himilco then launched a major raid with his entire fleet of 100 warships against Dionysius’ landing site, but withdrew when the numerically superior Syracusan fleet began to mobilize.[259] Motya fell after a vast siege and Dionysius utterly destroyed it, selling the survivors into slavery and crucifying the Greeks who had fought against him.[260] Himilco assembled a grand army from Libya and retaliated by seizing Messana with 200 ships and then razing it, cutting off Syracuse from its allies in southern Italy and forcing Dionysius to fall back to protect the city.[261]

Himilco next sent Mago ahead to Syracuse with his fleet. The Sicilian historian Diodorus, writing in the 1st century BC, states that Mago had 500 vessels, their intention being to supply and support the siege. Dionysius in desperation ordered his admiral Leptines to attack with his entire fleet, who then brazenly charged Mago’s line with his 30 best ships, inflicting some damage but soon being overcome and forced to flee, Mago destroying or capturing 100 of the scattered Syracusan vessels in the ensuing retreat.[262] The methodical Himilco soon arrived with the army, surrounded Syracuse on land, and blockaded the harbour.[263]

Syracuse was saved by an outbreak of pestilence (typhus) afflicting the Carthaginian lines,[264] and small Syracusan victories on land and at sea reduced Himilco’s fortunes further. He eventually negotiated a truce with Dionysius and then abandoned the campaign, leaving his allies to their fate. Himilco’s demoralized fleet was picked apart by Syracusan cruisers under Leptines and Pharacidas as it fled back to Carthage, where the general ignominiously expired.[265]

Plato the philosopher visited Syracuse in 388 when Dionysius was tyrant, there meeting the 20-year-old Dion.[266] In 386 Plato critiqued Dionysius in person at his court, the tyrant pettily ensuring some misfortune for the philosopher, who famously ended up in the Aeginetan slave market after departing Syracuse in 384.[267] Upon his return to Athens in 383 Plato founded the Academy with his ransom money, 20 silver minas, which had been paid by a charitable Libyan Greek named Anniceris and then guaranteed by Plato’s friends.[268] Dionysius meanwhile continued the war against Carthage, conquering several of their Sicilian allies in 383. Carthage responded by allying with the Greek cities in southern Italy oppressed by Dionysius, and despatched the usual amphibious armies to Sicily and Italy, this time under Mago with his “many tens of thousands”.[269]

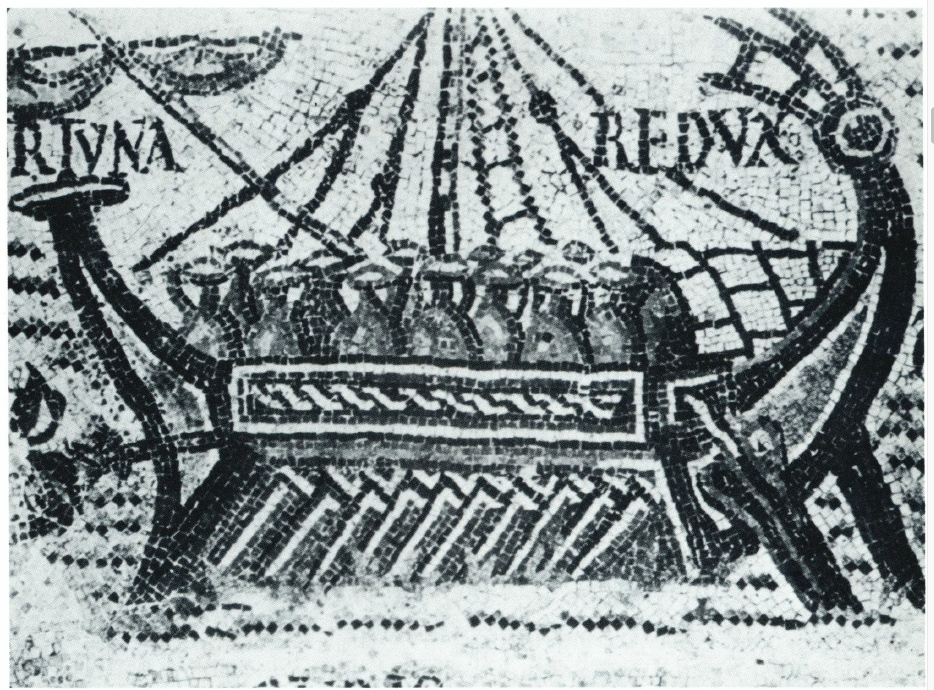

Roman freighter loaded with amphorae, from a mosaic in Tebessa, Algeria.

Size of Greek and Roman ships, from Alain Bresson, The Making of the Ancient Greek Economy (Princeton University Press, 2019), p. 87

Eastern Mediterranean ships of the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, and Roman ships from the 2nd century BCE to the 7th CE, from Lionel Casson, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World (Princeton University Press, 1971), p. 183-4, and 189-190

Dionysius in turn struck across the Straits of Messana, captured Locri and sieged Croton in southern Italy.[270] A Carthaginian counter-invasion of Magna Graecia meant to liberate Dionysius’ Greek holdings was unsuccessful. There was a protracted stalemate for five years, but eventually Dionysius was victorious over the Carthaginians in Sicily at the battle of Cabala (c. 282-277), where the Syracusan slew more than 10,000 of the enemy, including Mago himself, and captured at least another 5,000.[271] The Phoenicians asked for peace but were rebuffed by Dionysius unless they quitted Sicily altogether and paid the entire cost of the war.[272] The Carthaginians, however, presently restored the situation in 376 with their victory at Cronium, killing 14,000 Sicilians, and then retiring to Panormus in 373 when Dionysius at length agreed to their peace offer.[273] Dionysius ultimately paid the Carthaginians 1,000 talents, and Carthage retained Selinus, which it had been trying to secure since capturing it in 409, and more importantly the destruction of Acragas had taken an important Syracusan ally out of the war.[274]

The war had continued for 24 years at this point and, indeed, would continue sporadically by proxy for another six years until Dionysius was killed by his own subjects in 365 and succeed by his son, Dionysius II. In 367 Plato again visited Syracuse, this time in the capacity as sophist at the 30-year-old Dionysius II’s court, where he stayed until 365.[275] After Dionysius’ begging, and holding Dion’s property hostage, Dion was then staying with Plato in the Academy at Athens, Plato came for a third time to Syracuse briefly in 361.[276]

Unbeknownst to Dionysius II, the Carthaginians were hoping to leverage Dion into power as his replacement. Dion had been the Syracusan guest-friend of Carthage under Dionysius I, and they expected him to maintain the peace against the potentially belligerent Dionysius II.[277] Dion’s friends in Syracuse enjoined him, “simply to step into an open boat and lend the Syracusans his name.”[278]

Carthage sent armour and money to Dion through their Sicilian proxies Paralus and Hicetas and later, with Phoenician galleys, blockaded the Corinthians at Rhegium to prevent their intervention.[279] In 357 Dion, his entourage, and 800 fighters sailed to Sicily from Zacynthus with only five ships and 2,000 shields, rounded Cape Pachynus (Passero) where they were promptly blown towards the coast of Africa by a powerful September storm, and ended up sailing, hardly surprisingly, into Phoenician Sicily where they reached Heraclea Minoa, then under Carthaginian control.[280]

Syracuse coin, 357-4, at time of Dion

Dion, his brother Megacles, and Callippus the Athenian set off for Syracuse with about 6,000 men and at least 200 horses. Crowned with garlands as they approached the walls, the people “ran forward with shouts of joy,” and the leading citizens opened to Dion the Temenitid gate.[281] Dionysius fled from his citadel on Ortygia to Italy. Discovering this, Dion and his mercenaries rushed into the city where they were joined by many admirers from the population and quickly deposed Dionysius’ Neapolitan general Nypsius and his garrison who had attempt to burn the city down.[282] Dionysius’ admiral Heracleides joined with Dion, and his admiral Philistus committed suicide after being dealt a defeat by Syracuse.[283] Dion’s victory lasted only a few short years, however, and he was murdered in 354 in a mercenary conspiracy hatched by his own friend Callippus, who to Plutarch represented, “the sweetest honey and the deadliest hemlock” of Athens, leaving Dionysius II free to return triumphantly to Syracuse.[284]

Lest the reader despair at this point of the low fortunes of the Sicilians and Syracusans, oppressed by terrible Punic warfare and generations of tyrants, there was now the intervention in Sicily of a particular agent of fortune whose philosophic temperament, zeal for liberty and idealistic heroism, foreshadowed those forthcoming Hellenistic marshals, raised on the didactic humanistic writings of Plato, Xenophon, Isocrates and Aristotle, who from Macedon were about to step onto the world stage. Corinth was the mother-city of Syracuse, and it was to that isthmian polis in 344 that the people of Syracuse begged for help; for Dionysius’ regime was gradually collapsing as the influence of Carthage and its proxies grew.[285]

The 68-year-old Timoleon (411-337), son of Timodemus (Timaenetus) and Demariste, was selected for this high mission. Timoleon was a Corinthian soldier and a nobleman reputed for his hatred of tyrants – he had acquiesced to the assassination of his brother Timophanes who had sought the tyranny of Corinth in 365/4, to the idealistic Timoleon’s disgust.[286] Twenty years later the disinterested Timoleon now set sail for Rhegium with only ten ships, waiting for an opportunity to cross to Syracuse where the long-struggling Carthaginian agent Hicetas was besieging Dionysius in his citadel on the island of Ortygia.[287] As had been the case when Dion crossed to Sicily in 357, the Carthaginians were again blockading Rhegium, from which they refused to allow Timoleon to sail.[288] With singular purpose he invited the Carthaginian envoys into the city assembly and then delayed them by reverently hearing endless speeches from the sympathetic aldermen, while his triremes left harbour and Timoleon then quietly slipped away.[289]

Mercury piping to Argus, by Johann Carl Loth, c. 1655

Having thus trumped the Carthaginian blockade (which was under the command of Hanno), Timoleon sailed to Tauromenium (Taormina) in eastern Sicily, where he was welcomed by Andromachus, a respected statesman and father of the historian Timaeus, both of whom revered Timoleon.[290] With barely 1,200 men they set out for Adranum, another sympathetic city, with Hicetas marching to intercept the Corinthians with 5,000 men.[291] Timoleon personally led the attack on their camp, and the Corinthians caught Hicetas’ men as they were pitching their tents and cooking dinner and routed them, killing 300 and capturing 600.[292] Hearing of this victory the Sicilian cities began to come over to Timoleon, starting with Catana. The defeated Dionysius, trapped on Ortygia by Hicetas’ men, sent word to Timoleon that he would surrender to his cause and turn over his entire arsenal of armour, missiles, siege engines and 2,000 bodyguards. The Corinthians snuck a small detachment of 400 men led by Neon into the citadel to meet with Dionysius, who promptly surrendered and was later sent as a private citizen to Corinth.[293] Fifty days had passed since Timoleon’s landing at Tauromenium.

Corinth now despatched reinforcements to Italy in the form of 2,000 hoplites and 200 cavalry, but this force could not row the Straits due to the presence of the Carthaginian squadron of 20 under Hanno who was covering the crossing – although not very thoroughly.[294] Indeed, Hanno soon sailed back to Syracuse to investigate the situation there and the Corinthian hoplites at Thurii then marched to Rhegium where they requisitioned ferry boats and fishing craft and made the crossing to Sicily unopposed.[295] Timoleon rendezvoused with the Corinthians at Messana, and marched his whole force to Syracuse, having under his command only 4,000 men and some cavalry.